Teacher Outreach

Cleaver, S., Detrich, R., States, J. & Keyworth, R. (2021). Teacher Outreach. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/quality-teachers-outreach.

Teacher Outreach PDF

The goal of the education system is to provide every child with a high-quality education. Of all school resources, teachers have the greatest influence on student achievement (Darling-Hammond, Wei, & Johnson, 2009; Guarino, Santibañez, Daley, & Brewer, 2004; Wilson, Floden, & Ferrini-Mundy, 2001). Teachers also impact student motivation, self-efficacy, and other non-academic outcomes (Jackson, 2018). The importance of teachers makes teacher outreach and recruitment a high priority for districts (Darling-Hammond & Wei, 2009; Wilson et al., 2001).

Teacher outreach includes the work that districts do to recruit teachers into the profession. This includes recruiting teachers from traditional teacher preparation programs as well as alternative certification programs (e.g., Teach for America).

The purpose of this overview is to provide information about teacher outreach, the teacher labor market, teacher shortages, research, and recommendations.

Important questions about teacher outreach include:

- Who goes into teaching?

- What attracts teachers to the profession?

- What policies can increase the number of high-quality teachers in the applicant pool?

- What policies are effective in recruiting a more representative teaching workforce?

- What efforts can increase teacher recruitment to areas of shortage?

- Is there a difference between traditionally and alternatively certified teachers?

- What factors are most important when considering teacher candidates?

The Teaching Labor Market

Each year, 4 million teachers are employed across the United States (Congressional Research Service, 2019). As a labor market, the teaching market is driven by supply and demand. The demand for teachers, or the need of schools to provide a teacher for each classroom or group of students (e.g., special education) is driven by student enrollment, class-size targets, teaching load norms, and budget (Guarino et al., 2004).

The supply of teachers is the number of teachers who are looking for a job; it includes both recent graduates and teachers who are moving from one school to another (Guarino et al. 2004). While altruistic motives and associated intangible rewards are factors in the decision to enter the teaching profession (Aragon, 2016), teachers also pursue teaching for salary and working conditions (See, Morris, Gorard, Kokotsaki, & Abdi, 2020). As in other fields, “individuals will become teachers if teaching represents the most attractive activity to pursue among all those activities available to them” (Guarino et al., 2004, p. 3).

The teaching labor market is also driven by broader economic trends and policies. In general, people choose to become teachers when the economy is less stable (See et al., 2020). Federal, state, and district policies (e.g., salary bonuses targeted at teachers) have a great influence on the teaching market, either encouraging or discouraging people to become teachers.

Teacher quality is another aspect that influences supply and demand. Teacher quality is not a precise measure (Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, Ronfeldt, & Wyckoff, 2010). Policy may define teacher quality by certification status, test performance, or the quality of the teacher’s university. Or it may define teacher quality by practice-based measures such as experience or student test scores (Boyd et al., 2010). The parameters put on quality determine the number of teachers deemed high quality and influence supply.

Boyd et al. (2010) attempted to understand district hiring decisions. Using data from the New York City Department of Education’s application pool across two school years (2006–2007 and 2007–2008), they found that schools were more likely to hire “higher qualified” teachers as indicated by better pre-service qualifications (competitive college, test scores, more experience, and higher value-added scores). Of note, schools were more likely to hire alternatively certified applicants (e.g., Teach for America, New York City Teaching Fellows). There were relatively few Black and Hispanic teachers in the pool (32% of the teachers in the pool were Black or Hispanic compared with 75% of students). However, Black and Hispanic teachers were more likely to be hired than White applicants.

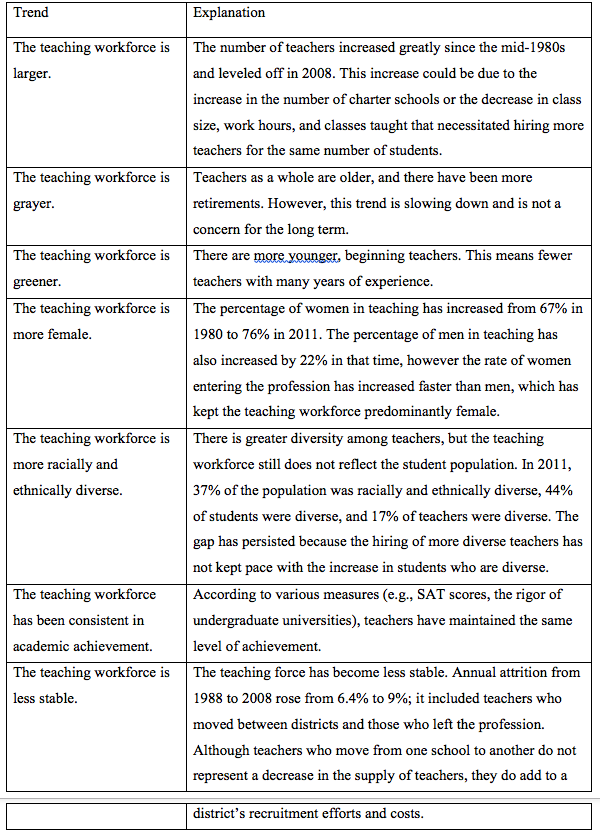

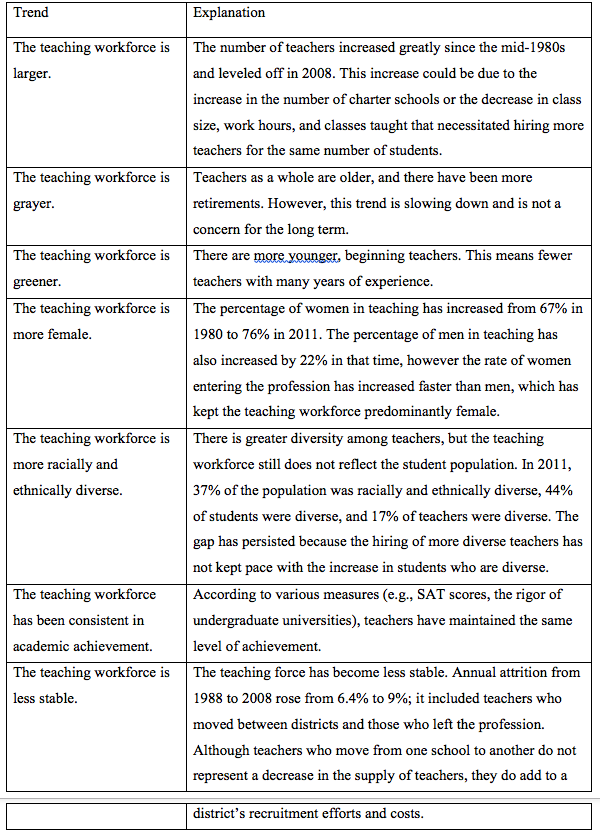

Ingersoll, Merrill, and Stuckey (2014) used the Schools and Staffing Survey and Teacher Follow-Up Survey to analyze trends in the teaching workforce from 1987 to 2012. They identified seven key trends (Table 1).

Table 1: Trends in the teaching workforce

Player (2015) analyzed the rural teaching labor market and found that while rural schools had a smaller number of vacancies than non-rural schools, this was likely because they employed fewer teachers overall. Rural schools were not more likely to report difficulty filling teaching positions except for teachers of English language learners. There was a gap in qualifications between teachers in rural schools and teachers in suburban or urban schools. For example, Fowles, Butler, Cowen, Streams, and Toma (2013) found that teachers in rural districts had lower skill levels than teachers in suburban and urban districts; for example, they were less likely to have graduated from a selective university, which may impact the quality of teachers in rural areas.

Federal and State Policies

Federal policymakers have attempted to address teacher quality and recruitment for decades. No Child Left Behind (2001) required that core academic classes be taught by highly qualified teachers, meaning that teachers had to have a bachelor’s degree, have earned their teaching certification, and demonstrate knowledge and skills in their subject area by passing a test or other criteria. It also required states to ensure that low-income and racially and ethnically diverse students were not taught by inexperienced, unqualified, or out-of-field teachers at higher rates than other students.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA; 2015) continued the focus on equity. The law required each state to identify how schools in low-income or high-poverty communities were not served disproportionately by ineffective or inexperienced teachers and authorized funding for “improving equitable access to effective teachers” (Berg-Jacobson, 2016, p. 2). ESSA also apportioned money to bolster teacher recruitment and increase the number of highly effective teachers.

Despite federal guidelines, students in high-poverty schools have remained more likely to be taught by teachers who are less qualified or not certified in the subject they teach (Clotfelter, Ladd, Vigdor, & Wheeler, 2006; Goldhaber, Quince, & Theobald, 2018; Sykes & Dibner, 2009). In the 2013–2014 school year, Black and Hispanic students were more likely to be taught by first-year teachers (Black, Giuliano, & Narayan, 2016). Research on the experiences of first-year teachers who decide to teach in high-poverty schools could strengthen how districts train and support early-career teachers to minimize potential achievement gaps (Black et al., 2016).

State legislatures have also tackled teacher recruitment. In 2017, at least 47 bills across 23 states were enacted to address teacher recruitment (Aragon, 2018) and to diversify the teaching workforce, including initiatives to recruit high-achieving people of color through Grow Your Own programs, residencies, and mentorships (Johnson, 2018). These initiatives are new and their effectiveness has yet to be examined.

Teacher Shortages

Although there is no national teacher shortage, supply and demand have been out of sync and have produced teacher shortages in some areas (Behrstock-Sherratt, 2016; Cowan, Goldhaber, Hayes, & Theobald, 2016; Viadero, 2018).There are persistent teacher shortages in STEM, special education, and specific districts, such as rural and urban schools across the country (Ingersoll, Merrill, Stuckey, & Collins, 2018; Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2016).

In an analysis of supply and demand, Sutcher et al. (2016) identified four factors that contribute to current shortages of teachers:

- Decline in enrollment in teacher preparation programs

- Increasing K–12 offerings to levels predating the 2008 recession, when many teachers were laid off

- Increases in student enrollment

- High rates of teacher attrition

Teacher shortages are projected to worsen as supply fails to keep up with demand (Sutcher et al., 2016). The teacher cuts that occurred during the Great Recession were long lasting; there were fewer teachers in 2019 than in 2008 (Griffith, 2020). This means fewer existing positions. Currently, the economy is in a recession because of COVID-19. It is difficult to gauge the impact that the COVID-19 recession may have on teaching, although the initial fears over many teacher retirements and resignations may not come to pass (Aspegren, 2020; Griffith, 2020).

Expected increases in public school enrollment, teacher retirements, attrition, and reduced student-teacher ratios will create demand for more teachers (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017; Hussar & Bailey, 2014; Ingersoll et al, 2018; Sutcher et al., 2016). Shortages are problematic because they result in inequitable distribution of high-quality teachers, which impacts outcomes for students who need high-quality instruction the most (Goldhaber, Gross, & Player, 2010; Goldhaber, Krieg, Theobald, & Brown, 2015; Hanushek, Kain & Rivkin, 2004).

Teacher shortages have a broader impact. An Economic Policy Institute analysis (García & Weiss, 2020) identifies teacher shortages that have developed since 2013 as a crisis for the education system, consuming resources and making it more difficult to advance teaching as a profession. The uneven distribution of high-quality teachers, which impacts students in low-income schools most directly, affects the goal of providing a high-quality education to all children.

Teacher outreach is an important way to mitigate teacher shortages and maintain a pipeline of highly qualified teachers. Addressing teacher shortages requires understanding who is becoming teachers.

Research on Teacher Outreach

The research on teacher recruitment has focused on some key questions.

Who Goes Into Teaching?

Overall, there have been some consistent trends in who becomes a teacher. More women than men enter teaching (Guarino et al., 2004). College graduates with higher academic ability (e.g., test scores) were less likely to enter teaching (Guarino et al., 2004). The teaching pool is not diverse; White teachers represent a higher proportion of new teachers (Guarino et al., 2004). The teaching workforce has become slightly more diverse over time but that has not kept pace with the diversity in the student population (Ingersoll, May, & Collins, 2017; U.S. Department of Education, 2016). Diversity is important because, compared with their peers, teachers from minority backgrounds are more likely to have higher expectations of students of color, be advocates, address racism, and develop stronger relationships with students (U.S. Department of Education, 2016).

What Attracts Teachers to the Profession?

Teachers enter the profession for a variety of reasons. Some reasons—salary and working conditions—are common to all professions, while others—altruism and the desire to make a difference—are distinctive to teaching.

Altruism and a desire to make a difference

Teachers may go into teaching for altruism or the desire to make a difference (Guarino et al., 2004). Comte (1875) defined altruism as “living for others.” The term is also defined as the values, preferences, and behaviors focused on meeting others’ needs rather than our own (Piliavin & Charng, 1990). Morality and altruism have long been identified as elements of teaching (Freeman, 1988; Locke, Vulliamy, Webb, & Hill, 2005).

Salary

Teacher pay can vary across districts and regions and, as a sector, education is in competition with other occupations (Loeb & Reininger, 2004). In particular, starting salaries are important to make a district attractive to new teachers; the higher the salary the higher the quality of teacher applicants (Adamson & Darling-Hammond, 2011).

On the whole, teacher salaries are relatively low. In 2010, teachers earned 15% to 30% less than holders of college degrees who entered other fields (Darling-Hammond, 2010). More recent reports indicate that average teacher salaries have been rising, but they do not always keep up with inflation (National Science Board, 2019). Because teacher quality directly impacts student achievement, increasing teacher salaries would likely increase student achievement (Ferguson, 1991).

Working conditions

Working conditions in schools include administrative support, resources for teaching, and teacher input into decision making (Darling-Hammond, 1997; Ingersoll, 2001; 2002; Loeb & Reininger, 2004). They can attract teachers to specific schools and are a factor in teacher retention and attrition (Darling-Hammond, 2010). There are differences in working conditions between high- and high-poverty schools, which influences teacher retention in high-poverty schools (Henke, Choy, Chen, Geis, & Alt, 1997).

One important aspect of working conditions is the quality of the building; good facilities can reduce teacher turnover (Filardo, Vincent, & Sullivan, 2019). A 2002 survey of teachers in Chicago and Washington, D.C., found that teachers working in run-down schools were more likely to report plans to leave (Buckley, Schneider, & Shang, 2004). Another study found that when schools improved ventilation and air quality, teachers reported greater job satisfaction (Batterman et al., 2017). Working in good-quality buildings encourages teacher retention and satisfaction, particularly when teachers are asked to prepare students for a workforce rich in technology (Filardo et al., 2019).

What Policies Can Increase the Number of High-Quality Teachers in the Applicant Pool?

Increasing salary

When teacher salaries are lower than other career options, it impacts retention (Aragon, 2016). There have been efforts to address this. Currently, seven states have a minimum salary requirement for teachers; 17 states have a set salary schedule that bases teacher pay on credentials and experience (Aragon, 2016). However, even when salaries are higher, districts must be strategic with hiring to retain teachers (Hough & Loeb, 2013).

There has been interest in creating variable salary structures to attract teachers to certain districts or areas, and in rewarding teachers for performance (See et al., 2020). Hough (2012) investigated salary increases in San Francisco and found that a differential salary increase, in this case, that aligned the teaching salary in San Francisco with salaries in surrounding communities, can improve a district’s attractiveness to local teachers and increase the size and quality of the applicant pool. This suggests that making sure teaching salaries are consistent across a region has potential to make urban districts more competitive with neighboring districts and increase the quality of new hires (Hough, 2012; Hough & Loeb, 2013).

Not all experts agree on general increases in teacher salaries, however. Hanushek and Rivkin (2007) suggested that overall salary increases for teachers may not be effective. Instead, they suggested removing barriers to becoming a teacher (e.g., certification tests) and linking compensation and career advancement to improve teacher quality and instruction.

Financial incentives

Since the 1944 G.I. Bill of Rights, the federal government has used financial incentives to encourage young adults to go into teaching; the primary methods used have been service payback, loan forgiveness, and grants or fellowships (Sykes & Dibner, 2009). There have also been efforts aimed at increasing the number of STEM and special education teachers to address teacher shortages. Sykes and Dibner (2009) found that high-poverty and high-minority districts were more likely to offer financial incentives.

In their metasynthesis of 120 studies on teacher recruitment and retention, See et al. (2020) found mixed outcomes for providing financial incentives to go into teaching. Financial incentives were a promising way to attract new teachers and to increase the number of teachers in hard-to-staff schools. However, for higher performing schools and schools with lower proportions of low-income students, the effect was higher. This indicates that financial incentives must be large enough to compensate for the challenges of working in hard-to-staff schools or to make teaching more desirable than other professions. This is particularly true for STEM teachers, when science and technology jobs typically provide a much higher salary.

Henry, Bastian, and Smith (2012) examined whether or not college scholarships for teachers were effective in increasing the teaching pool. They found that a merit-based scholarship program attracted candidates with high academic qualifications and produced teachers who were more likely to teach lower performing students, raise test scores in certain areas (math in high school, and third and eighth grades), and stay in classrooms for at least five years.

Liou, Kirchhoff, and Lawrenz (2010) examined a scholarship program to attract STEM majors to high-need schools. They analyzed the perceptions of 555 scholarship recipients and found that the majority of recipients connected their scholarships with completing their teaching certification and working in a high-need school.

On the whole, recruitment strategies should identify those who are committed to teaching in high-need schools and encourage that commitment through financial efforts. For a financial incentive to work over time, teachers must believe that it will stay in place; frequent budget and leadership shifts can make teachers think that financial incentives will not be maintained (Hough & Loeb, 2013).

Accountability measures

Kraft, Brunner, Dougherty, and Schwegman (2020) examined the impact of teacher accountability measures (e.g., student testing, high-stakes teacher evaluations) on teacher recruitment and retention. They found that when accountability measures were in place, fewer people were granted licenses to teach, resulting in fewer but higher quality teachers for high-need schools.

Accountability measures may have discouraged potential candidates because they perceived a decrease in job security and autonomy. More research should be done on the impact of accountability measures on both teacher recruitment and student achievement to examine exactly how these elements intersect, and what level of accountability would have a positive impact on recruitment and achievement.

What Policies Are Effective in Recruiting a More Representative Teaching Workforce?

Given the persistent gap between the percentages of diverse students and diverse teachers, it is important to enact efforts to increase the number of diverse teachers (Ingersoll, May, & Collins, 2017). Efforts to recruit diverse teachers to teach in hard-to-staff schools have been successful. The number of teachers of color has increased, and teachers of color are overwhelmingly employed in public schools that serve high-poverty, high-minority, urban communities.

One approach to recruiting a teaching workforce that more accurately reflects local communities are Grow Your Own (GYO) programs. Gist, Bianca, and Lynn (2019) examined these programs and found that they did not specifically focus on recruiting and developing teachers of color. There has been little to no research on GYO programs and the types of supports offered to teachers of color, or the impact on future students. Additional research on the effectiveness of GYO programs in the long term and what districts can expect when implementing these programs would help decision making.

Sutton, Bausmith, O’Connor, Pae, and Payne (2014) conducted a study on attracting special education teachers to rural schools in South Carolina through a GYO program. Among the 638 participants in both rural and non-rural districts who completed the special education program across 8 years (2003 to 2011), a significantly higher percentage of completers were in the rural group. The researchers found that the rural group had fewer program completers in the areas of emotional disabilities and more completers in the area of multicategorical disabilities. This was not surprising because teachers of students with emotional disabilities have typically been more difficult to recruit and retain. Overall, the GYO program provided a more equitable distribution of special education teacher program completers across the state, and increased teacher capacity building in high-needs districts (e.g., rural, higher poverty).

What Efforts Can Increase Teacher Recruitment to Areas of Shortage?

It is important to recruit teachers for STEM, special education, and other regional areas of shortage. Feng and Sass (2015) studied the effects of the Florida Critical Teacher Shortage Program, an effort to increase the supply of teachers in hard-to-staff areas. The program provided loan forgiveness, compensation for tuition costs, and bonuses to high school teachers who taught in designated subject areas. The loan forgiveness program decreased attrition, and effects were larger when loan forgiveness payments were larger. Tuition reimbursement had modest positive effects on the likelihood that a teacher would get certified in an area of shortage. The program improved the quality of teachers but did not recruit more teachers to apply to the district.

Another way to increase teacher quality in hard-to-staff schools is by encouraging established teachers to transfer to these schools. Glazerman, Protik, Teh, Bruck, and Max (2013) studied the use of selective transfer initiatives to increase access to effective teachers. These incentives provided bonuses for high-performing teachers to move into hard-to-staff schools. The intervention, Talent Transfer Initiative (TTI), was implemented in 10 districts across seven states. The highest performing teachers in each district (teachers who were in the top 20% in subject and grade in terms of raising student achievement) were offered $20,000 to transfer to schools with lower test scores. They found that the transfer initiative successfully attracted high-performing teachers to targeted vacancies. A large majority (88%) of vacancies were filled through this intervention.

Glazerman et al. also found a positive impact on test scores (math and reading) in targeted elementary classrooms. Two years after the teachers transferred, the result was equivalent to moving each student up by 4 to 10 percentile points relative to all students in their state. Finally, the transfer incentive had a positive impact on teacher retention rates during the payout period. After payments stopped, the difference in retention between teachers who had and had not received the payment was not significant.

Is There a Difference Between Traditionally and Alternatively Certified Teachers?

Teacher certification serves as a proxy for the knowledge and skills that teachers have when they start teaching (Darling-Hammond, Berry, and Thoreson, 2001).

Alternative certification refers to programs that provide teaching certification after a brief training, such as Teach for America (TFA). High-poverty and high-minority schools are more likely to have teachers who completed alternative certification programs (Sykes & Dibner, 2009). On the whole, alternative certification programs do recruit more teachers for a district, and teacher recruits have higher academic qualifications than traditionally certified teachers (See et al., 2020). For example, the New York City Mathematics Immersions program attracted more teachers to teach math, a critical area of need (Boyd et al., 2012).

Both traditional and alternative certification programs provide paths to teaching certification, but is there a difference in between traditionally and alternatively certified teachers’ outcomes in the classroom? In short, the answer is no. A study of K–5 teachers found no difference between the two cohorts of alternate and traditional certification teachers on important educational criteria (Constantine et al., 2009). There was also no statistically significant difference in student outcomes produced by the teachers (Constantine et al., 2009).

Bos and Gerdeman (2017) matched teachers trained through the New Teachers Project (now TNTP) in their first 2 years of teaching with traditionally trained teachers in their first two years of teaching and found no difference in teacher performance or student achievement.

Whether teachers come into the profession through traditional or alternative programs, preparation and certification do have an impact. Darling-Hammond, Holtzman, Gatlin, and Heilig (2007) analyzed the achievement gains of fourth and fifth-grade reading and math scores across a six-year period in Texas. They found that, overall, the effects of teachers, either TFA or traditionally certified, depended on their level of preparation. Also, teachers who were fully certified through traditional or alternative programs, produced stronger achievement gains than teachers who had not completed their certification process and were un-certified or who had less than a standard certification.

What Factors Are Most Important When Considering Teacher Candidates?

A teaching credential and some sort of training are prerequisites for applying for a teaching job. Research does not provide decisive direction on the impact of credentials and pre-service training on teacher quality. In general, there are mixed results regarding teacher credentials and small positive effects with subject-area preparation (Guarino et al., 2004).

On the whole, a master’s degree program in teaching does not produce teachers who are more effective (Clotfelter, Ladd, & Vigdor, 2007a, 2007b; Goldhaber, 2002). Chingos and Peterson (2011) found that majoring in education or earning a master’s degree in education was not associated with greater effectiveness. The university that a teacher candidate attended was also not associated with greater effectiveness in the classroom. Similarly, Clotfelter et al. (2007a) studied the effect of teaching credentials on the achievement of students in grades 3, 4, and 5 across North Carolina from 1994 to 2003. They found that having a graduate degree had little effect on student achievement. Teachers who entered teaching with a master’s degree, or who earned it within their first 5 years of teaching, were no more effective than teachers without a master’s degree.

On the other hand, experience in the classroom did improve teachers’ performance (Chingos & Peterson, 2011; Kini & Podolsky, 2016). Kini and Podolsky reviewed 30 studies over 15 years that addressed how teacher experience impacted student achievement. Teaching experience was positively associated with student achievement gains throughout a career. The gains were steepest in the initial years but continued into subsequent decades. As teachers gained experience, students did better on achievement tests and other measures (e.g., attendance). Teacher effectiveness increased when teachers accumulated experience in the same grade level, subject, or district.

Teacher experience has demonstrated a connection with student achievement (Guarino et al., 2004). For example, Fetler (1999) found a positive relationship between number of years of teaching high school and students’ math scores. Rowan, Correnti, and Miller (2002) found a positive effect of teachers’ experience on student growth in math achievement in grades 3 to 6.

Staffing all positions with teachers who have years of experience may be difficult. Recent university graduates will not have that level of experience but must be hired to build a sustainable teaching workforce. When evaluating teacher candidates who are moving from one school to another, it may be worth considering years of experience over education. Not enough is known about how student teaching prepares teachers to be highly effective teachers (Cleaver, Detrich, States, & Keyworth, 2020). However, having a math teacher who is not well qualified (e.g., low scores on a licensing exam, little experience, a degree from a non-competitive university, emergency license) reduces the likelihood that students will make progress in math. This suggests that having teachers with weak credentials in classrooms with low-income students could widen existing achievement gaps already associated with socioeconomic differences (Clotfelter et al., 2007a). This also points to the importance of hiring the strongest teaching candidates for the schools and students that most need them.

Recommendations for Teacher Outreach

Policies do have an impact on whether individuals decide to enter teaching (or not), and districts and schools can implement policies to increase their attractiveness to prospective teachers (Guarino et al., 2004). These policies must address salary, working conditions, preparation, and mentoring and support (Darling-Hammond, 2010). On a broader scale, policies should also work to equalize the job market for hard-to-staff schools, primarily in urban and rural districts.

Set Policy to Support Staffing High-Need Schools

Darling-Hammond and Sykes (2003) suggested that teacher recruitment policy focus on attracting well-prepared teachers to the highest need schools, for example, urban schools and schools with high percentages of minority students (Guarino et al., 2004). Ensuring that teacher pay is competitive in each local job market, and incentivizing teacher hires to be fully certified will increase the quality of teachers and make it easier for low-income districts to recruit teachers.

To increase the number of teacher candidates and the equity of teacher candidates for hard-to-staff schools, Adamson and Darling-Hammond (2011) recommended:

- Federal strategies: Equalize federal (e.g., ESSA) funding and resources across states so that all states can recruit high-quality teachers.

- State and district strategies: Improve salaries to increase the teacher pool across districts and align teacher salaries with the local cost of living. Simultaneously increase teacher standards as well as knowledge and skills through licensing standards, evaluations, and professional development.

Use Financial Incentives Strategically

While the overall results are mixed, financial incentives are a promising way to encourage more teachers to apply to hard-to-staff schools (See et al., 2020). They include increasing salaries to attract more people to teaching (Aragon, 2016), and raising local salaries in relation to neighboring districts to increase the teaching pool in a specific area (Hough, 2012). Financial incentives must occur within broader policies that support teacher recruitment (Hough & Loeb, 2013) and should be combined with other less costly reforms (Aragon, 2016).

Set Policies for Rural Districts

Salaries are typically lower in rural districts, discouraging teacher candidates from applying there (Provasnik et al., 2007; Player, 2015). Providing bonuses (e.g., shortage pay) could help rural districts attract teachers, particularly as these districts do not use bonuses as frequently as urban districts (Player, 2015).

Focus on Working Conditions

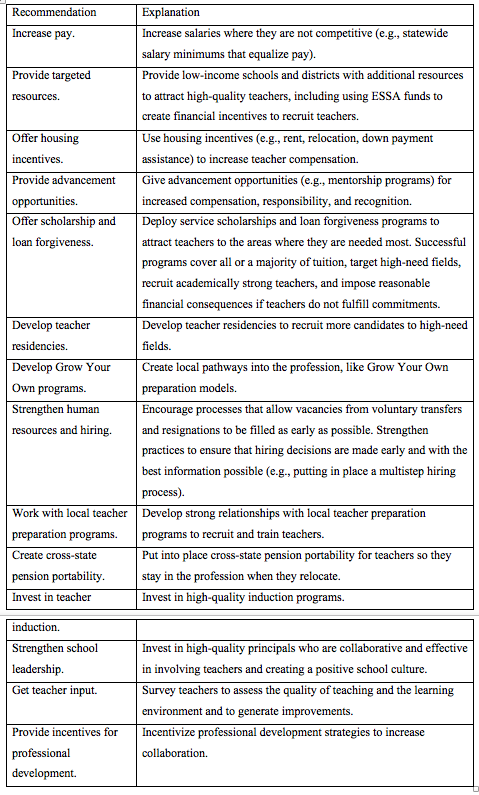

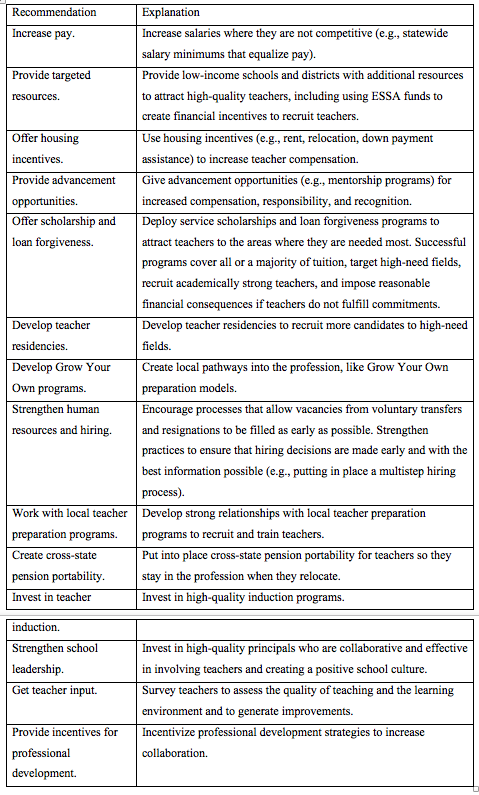

Supportive working conditions (e.g., administrative support, resources provided, teacher input in decision making) can impact teacher recruitment (Darling-Hammond, 2010). Federal, state, and local governments could put in place various policies to increase teacher recruitment and retention (Podolsky, Kini, Bishop, & Darling-Hammond, 2016; Table 2).

Table 2: Recommendations to increase teacher recruitment and retention

The Economic Policy Institute (García & Weiss, 2020) has outlined policy proposals to address the teacher shortage:

- Raise pay to attract and retain teachers.

- Elevate teacher voices and cultivate stronger learning communities to increase teachers’ sense of belonging and influence.

- Lower barriers to teaching.

- Design professional supports to strengthen teaching as a career.

Cost of Teacher Recruitment

The cost to recruit new teachers is individual to each district and its needs and resources. Return on investment can be thought of as the cost per application, per qualified applicant, or per hire (Howard & Tam, 2019). When considering cost, it is important to recruit teachers who will stay in the profession to reduce future costs related to turnover, which has negative long-lasting effects for districts (Sorenson & Ladd, 2018).

Conclusion

Teacher recruitment is a high priority for districts, and staffing classrooms with high-quality teachers is especially urgent for high-need schools. Federal, state, and local policies have an impact on how many teachers seek employment. Alternative certification and Grow Your Own programs can provide a way to boost the number of qualified candidates in the teaching pool. Additionally, strategic use of financial incentives is effective in attracting teachers to the profession.

Citations

Adamson, F., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2011). Speaking of salaries: What it will take to get qualified, effective teachers in all communities. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/speaking-salaries-what-it-will-take-get-qualified-effective-teachers-all-communities.pdf

Aragon, S. (2016). Mitigating teacher shortages: Financial incentives. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States. https://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/Mitigating-Teacher-Shortages-Financial-incentives.pdf

Aragon, S. (2018). Targeted teacher recruitment. What is the issue and why does it matter? Policy Snapshot. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States. http://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/Targeted_Teacher_Recruitment.pdf

Aspegren, E. (2020, October 8). Fears of a mass exodus of retiring teachers during COVID-19 may have been overblown. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/10/08/fear-mass-teacher-retirements-covid-19-may-have-been-overblown/3433963001/

Batterman, S., Su, F. C., Waid, A., Watkins, F., Godwin, C., & Thun, G. (2017). Ventilation rates in recently constructed U.S. school classrooms. Indoor Air, 27 (5), 880–890.

Behrstock-Sherratt, E. (2016). Creating coherence in the teacher shortage debate: What policy leaders should know and do. Washington, DC: Education Policy Center at American Institutes for Research. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED582418.pdf

Berg-Jacobson, A. (2016). Teacher effectiveness in the Every Student Succeeds Act: A discussion guide. Washington, DC: Center on Great Teachers and Leaders at American Institutes for Research. https://gtlcenter.org/sites/default/files/TeacherEffectiveness_ESSA.pdf

Black, S., Giuliano, L., & Narayan, A, (2016, December 9). Civil rights data show more work is needed to reduce inequities in K–12 schools. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/12/08/civil-rights-data-show-more-work-needed-reduce-inequities-k-12-schools

Bos, H., & Gerdeman, D. (2017). Alternative teacher certification: Does it work? Washington, DC: American Institutes of Research. https://www.air.org/resource/alternative-teacher-certification-does-it-work

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Ronfeldt, M., & Wyckoff, J. (2012). Recruiting effective math teachers: Evidence from New York City. American Education Research Journal, 49(6), 1008–1047.

Boyd, D., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Ronfeldt, M., & Wyckoff, J. (2010). The role of teacher quality in retention and hiring: Using applications-to-transfer to uncover preferences of teachers and schools. Working Paper No. 15966. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w15966.pdf

Buckley, J., Schneider, M., & Shang, Y. (2004). The effects of school facility quality on teacher retention in urban school districts. Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for Educational Facilities.

Carver-Thomas, D. & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Turnover_REPORT.pdf

Chingos, M. M., & Peterson, P. E. (2011). It’s easier to pick a good teacher than to train one: Familiar and new results on the correlates of teacher effectiveness. Economics of Education Review, 30(3), 449–465.

Cleaver, S., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, R. (2020). Overview of teacher induction.

Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.winginstitute.org/pre-service-student

Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007a). How and why do credentials matter for student achievement? Working Paper No. 12828. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w12828

Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H.F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007b). Teacher credentials and student achievement: Longitudinal analysis with student fixed effects. Economics of Education Review, 26(6), 673–682.

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J., & Wheeler, J. (2006). High-poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. North Carolina Law Review, 85(5), 1345–1379.

Comte, A. (1875). System of positive polity. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Congressional Research Service. (2019, September 4). K-12 teacher recruitment and retention policies in the Higher Education Act: In brief. https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R45914.html

Constantine, J., Player, D., Silva, T., Hallgren, K., Grider, M., & Deke, J. (2009). An evaluation of teachers trained through different routes to certification (NCEE 2009- 4043). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20094043/pdf/20094044.pdf

Cowan, J., Goldhaber, D., Hayes, K., & Theobald, R. (2016). Missing elements in the discussion of teacher shortages. Educational Researcher, 45(8), 460–462.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1997). Doing what matters most: Investing in quality teaching. New York, NY: National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Recruiting and retaining teachers: Turning around the race to the bottom in high-need schools. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 4(1), 16–32.

Darling-Hammond, L., Berry, B., & Thoreson, A. (2001). Does teacher certification matter? Evaluating the evidence. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(1), 57–77.

Darling-Hammond, L., Holtzman, D. J., Gatlin, S. J., & Heilig, J. V. (2005). Does teacher preparation matter? Evidence about teacher certification, Teach For America, and teacher effectiveness. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13(42), 1-47. Retrieved from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ846746

Darling-Hammond, L., and Sykes, G. (2003). Wanted: A national teacher supply policy for education: The right way to meet the “highly qualified teacher” challenge. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11(33), 1–55.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Wei, R. C. (2009). Teacher preparation and teacher learning: A changing policy landscape. In G. Sykes, B. Schneider, & D. N. Plank (Eds.), The Handbook of Education Policy Research (pp. 613–636). Washington, DC: American Education Research Association.

Every Student Succeeds Act. (2015). Pub. L. 1114–95. Retrieved from: https://congress.gov/114/plaws/publ95/PLAW-114publ95.pdf

Feng, L., & Sass, T. R. (2015). The impact of incentives to recruit and retain teachers in “hard-to-staff” subjects: An analysis of the Florida Critical Teacher Shortage Program. Working Paper No. 141. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED587182.pdf

Ferguson, R. F. (1991). Paying for public education: New evidence on how and why money matters. Harvard Journal on Legislation, 28(2), 465–498.

Fetler, M. (1999). High school staff characteristics and mathematics test results. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 7(9). Retrieved from: http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/viewFile/544/667

Filardo, M., Vincent, J. M., & Sullivan, K. J. (2019). How crumbling school facilities perpetuate inequality. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (8), 27–31. https://kappanonline.org/how-crumbling-school-facilities-perpetuate-inequality-filardo-vincent-sullivan/

Fowles, J., Butler, J. S., Cowen, J. M. Streams, M. E., & Toma, E. F. (2013). Public employee

quality in a geographic context: A study of rural teachers. The American Review of Public Administration, 44(5), 503-521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074012474714

Freeman, H. R. (1988). Perceptions of teacher characteristics and student judgments of teacher effectiveness. Teaching of Psychology, 15(3), 158–160.

García, E., & Weiss, E. (2020). A policy agenda to address the teacher shortage in U.S. public schools. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/a-policy-agenda-to-address-the-teacher-shortage-in-u-s-public-schools/

Gist, C. D., Bianco, M., & Lynn, M. (2019). Examining Grow Your Own programs across the teacher development continuum: Mining research on teachers of color and nontraditional educator pipelines. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(1), 13–25. https://sehd.ucdenver.edu/impact/files/JTE-GYO-article.pdf

Glazerman, S., Protik, A., Teh, B., Bruch, J., & Max, J. (2013). Transfer incentives for high- performing teachers: Final results from a multisite randomized experiment (NCEE 2014-4003). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED544269.pdf

Goldhaber, D. (2002). The mystery of good teaching. Education Next, 2(1), 50–55.

Goldhaber, D., Gross, B., & Player, D. (2010). Teacher career paths, teacher quality, and persistence in the classroom: Are public schools keeping their best? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 30(1), 57–87.

Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., Theobald, R., & Brown, N. (2015). Refueling the STEM and special education teacher pipelines. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(4), 56–62.

Goldhaber, D., Quince, V., & Theobald, R. (2018). Has it always been this way? Tracing the evolution of teacher quality gaps in U.S. public schools. American Educational Research Journal, 55(1), 171–201.

Griffith, M. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 recession on teaching positions. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/impact-covid-19-recession-teaching-positions

Guarino, C. M., Santibañez, L., Daley, G. A., & Brewer, D. J. (2004). A review of the research literature on teacher recruitment and retention. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR164.html

Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J., & Rivkin, S. (2004). Why public schools lose teachers. Journal of Human Resources, 39(2), 326–354.

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2007). Pay, working conditions, and teacher quality. The Future of Children, 17(1), 69–86. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ795875.pdf

Henke, R. R., Choy, S. P., Chen, X., Geis, S., & Alt, M. N. (1997). America's teachers: Profile of a profession, 1993–94. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs97/97460.pdf

Henry, G. T., Bastian, K. C., & Smith, A. A. (2012). Scholarships to recruit the “best and brightest” into teaching: Who is recruited, where do they teach, how effective are they, and how long do they stay? Educational Researcher, 41(3), 83–92.

Howard, J., & Tam, W. (2019, September 18). Teacher recruitment ROI: What’s yours?https://blog.getselected.com/2019/09/18/teacher-recruitment-roi/

Hough, H. J. (2012). Salary incentives and teacher quality: The effect of a district-level salary increase on teacher recruitment. Center for Education Policy Analysis. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/salary-incentives-and-teacher-quality-effect-district-level-salary-increase-teacher-recruitment

Hough, H., & Loeb, S. (2013). Can a district-level teacher salary incentive policy improve teacher recruitment and retention? Stanford, CA: Policy Analysis for California Education. https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/can-district-level-teacher-salary-incentive-policy-improve-teacher-recruitment-and-retention

Hussar, W. J., & Bailey, T. M. (2014). Projections of education statistics to 2022 (NCES 2014-051). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014051.pdf

Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499–534.

Ingersoll, R. M. (2002). Out-of-field teaching, educational inequality, and the organization of schools: An exploratory analysis (Document R-02-1). Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from: https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1057&context=cpre_researchreports

Ingersoll, R., May, H., & Collins, G. (2017). Minority teacher recruitment, employment, and retention: 1987 to 2013. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Minority_Teacher_Recruitment_REPORT.pdf

Ingersoll, R. M., Merrill, L., & Stuckey, D. (2014). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force—updated April 2014. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. http://www.cpre.org/sites/default/files/workingpapers/1506_7trendsapril2014.pdf

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., & Collins, G. (2018). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force—updated October 2018. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=cpre_researchreports

Jackson, C. K. (2018). What do test scores miss? The importance of teacher effects on non-test score outcomes. Journal of Political Economy, 126(5), 2072–2107.

Johnson, S. (2018, February 5). These states are leveraging Title II of ESSA to modernize and elevate the teaching profession. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2018/02/05/445891/states-leveraging-title-ii-essa-modernize-elevate-teaching-profession/

Kini, T., & Podolsky, A. (2016). Does teaching experience increase teacher effectiveness? A review of the research. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/does-teaching-experience-increase-teacher-effectiveness-review-research

Kraft, M. A., Brunner, E. J., Dougherty, S. M., Schwegman, D. J. (2020). Teacher accountability reforms and the supply and quality of new teachers. Journal of Public Economics, 188.

Liou, P. Y., Kirchhoff, A., & Lawrenz, F. (2010). Perceived effects of scholarships on STEM majors’ commitment to teaching in high need schools. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 21(4), 451–470.

Locke, T., Vulliamy, G., Webb, R., & Hill, M. (2005). Being a “professional” primary school teacher at the beginning of the 21st century: A comparative analysis of primary teacher professionalism in New Zealand and England. Journal of Education Policy, 20(5), 555–581.

Loeb, S., & Reininger, M. (2004). Public policy and teacher labor markets: What we know and why it matters. East Lansing, MI: Education Policy Center at Michigan State University. https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/public-policy-and-teacher-labor-markets-what-we-know-and-why-it-matters

National Science Board. (2019, September 24). Science and engineering indicators. Public school teacher salaries (dollars). https://ncses.nsf.gov/indicators/states/indicator/public-school-teacher-salaries

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, P.L. 107-110, 20 U.S.C. § 6319 (2002)

Piliavin, J. A., & Charng, H. W. (1990). Altruism: A review of recent theory and research. The Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 27–65.

Player, D. (2015). The supply and demand for rural teachers. Boise, ID: Rural Opportunities Consortium of Idaho. http://www.rociidaho.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ROCI_2015_RuralTeachers_FINAL.pdf

Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Solving_Teacher_Shortage_Attract_Retain_Educators_REPORT.pdf#page=19

Provasnik, S., KewalRamani, A., Coleman, M., Gilbertson, L., Herring, W., & Xie, Q. (2007). Status of education in rural America (No. NCES 2007-040). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2007040

Rowan, B., Correnti, R., & Miller, R. (2002). What large-scale survey research tells us about teacher effects on student achievement: Insights from the Prospects study of elementary schools, teachers. Teachers College Record, 104(8), 1525–1567.

See, B. H., Morris, R., Gorard, S., Kokotsaki, D., & Abdi, S. (2020). Teacher recruitment and retention: A critical review of international evidence of most promising interventions. Education Sciences, 10(10), 262.

Sorensen, L. C., & Ladd, H. F. (2018). The hidden costs of teacher turnover. Working Paper No. 203-0918-1. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). https://caldercenter.org/publications/hidden-costs-teacher-turnover

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Sutton, J. P., Bausmith, S. C., O’Connor, D. M., Pae, H. A., & Payne, J. R. (2014). Building special education teacher capacity in rural schools: Impact of a Grow Your Own program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 33(4), 14–23. http://www.sccreate.org/Research/article.CREATE.RSEQ.14.pdf

Sykes, G., & Dibner, K. (2009). Fifty years of federal teacher policy: An appraisal. Washington, DC: Center on Education Policy. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505035.pdf

U.S. Department of Education. (2016). The state of racial diversity in the educator workforce. Washington, DC: Author. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/highered/racial-diversity/state-racial-diversity-workforce.pdf

Viadero, D. (2018, January 23). Teacher recruitment and retention: It’s complicated. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/teacher-recruitment-and-retention-its-complicated/2018/01

Will, M. (2020, June 3). Teachers say they are more likely to leave the classroom because of coronavirus. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/teachers-say-theyre-more-likely-to-leave-the-classroom-because-of-coronavirus/2020/06

Wilson, S., Floden, R., & Ferrini-Mundy, J. (2001). Teacher preparation research: Current knowledge, gaps, and recommendations. Seattle, WA: Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy.