Curriculum Content for Teacher Training Overview

Curriculum Content for Teacher Training PDF

Cleaver, S., Detrich, R., States, J. & Keyworth, R. (2021). Curriculum Content for Teacher Training Overview . Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/pre-service-teacher-curriculum-content.

Teachers have the greatest impact on student achievement in schools (Goldhaber, 2016). Most teachers will have completed a university teacher preparation program or an alternative certification program, and what they learned in these programs—that is, the curriculum content—matters. Curriculum content includes the skills that teachers need to know and master to be effective in their own classrooms. They must be taught core competencies that they can immediately apply to the classroom.

It is important to note the limitations in teacher training. First, teacher candidates have only so much time, whether they are completing a 4-year undergraduate degree or a 2-year alternative certification program. Second, teacher candidates are taught curriculum content along with other coursework (e.g., subject matter courses, university requirements) and experiences (e.g., student teaching). Finally, the job of teaching and working in schools is dynamic and responsive to local, state, and federal policies. Because of these limitations, the content that teacher candidates learn must be focused, impactful, and aligned with the realities of the job.

This overview focuses on content that all teachers should know, regardless of grade level or material taught. It does not cover experiences that teacher candidates should have (e.g., student teaching) or content knowledge (e.g., science, math).

Important questions about curriculum content include:

- What knowledge and skills should teacher candidates master?

- Is there alignment between what districts want in new teachers and what teacher education programs teach?

History of Curriculum Content

For much of American history, prospective teachers had to complete relatively few requirements to enter teaching. At the beginning of the 19th century, for example, they had only to convince a local school board to hire them based on a test of general knowledge and their moral character (Ravitch, 2003). In 1834, Pennsylvania was the first state to require teachers to pass a reading test, and by 1867 most states required a state certificate with a focus on content, for example, history, geography, and spelling (Ravitch, 2003). In the 20th century, teacher training became more standardized as schools of education worked to professionalize teaching. Becoming a teacher increasingly involved taking courses in pedagogy and passing tests about methods (Ravitch, 2003).

The localized focus of teacher preparation programs shifted in the 1980s, when, in response to poor test scores and a shortage of certified teachers, federal lawmakers focused on preparation programs as a way to improve student achievement (States et al., 2012). Since then, public policy has focused on teacher quality and preparing effective teachers to raise student achievement (States et al., 2012). Both No Child Left Behind (2001) and the subsequent Every Student Succeeds Act (2015) focused on those aspects (Klein, 2018). Despite the emphasis on high-quality teachers, states have still varied in their requirements for certification; teachers may receive different training and skills depending on which program they attend (States et al., 2012).

In the 21st century, the job of teaching is increasingly complex. Teachers must prepare students to meet standards, reduce achievement gaps and address social inequality, and implement education reforms (Cochran-Smith & Villegas, 2015). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the skills teachers need to be successful, and will likely change the daily work of teaching in the future (Holdheide, 2020).

Teacher preparation programs provide a broad scope of content. In a survey of more than 3,000 teachers, respondents indicated that they had received more instruction in maintaining a positive classroom culture, maximizing learning time, using classroom time productively, and conveying the importance of learning (Goodson et al., 2019). The teachers who were surveyed identified fewer opportunities to learn about effective instruction for English language learners, building comprehension of academic concepts, effective math instruction, and providing feedback that helps students learn.

Research on Curriculum Content

Fortunately, decades of research tell us what teacher candidates need to know and do for success in the classroom. That research can also provide answers to the important questions about curriculum content.

What Knowledge and Skills Should Teacher Candidates Master?

Multiple studies have identified the expertise that teacher candidates should have (Hattie, 2009; Kavale, 2005). The most important topics and skills that teachers must master to support student achievement are:

- Formative assessment,

- Classroom management,

- Teaching strategies, and

- Ability to implement well-designed curriculum instruction in writing, math, science, and reading (e.g., phonics)

Although personal competencies or soft skills are not included in this list, they are also vital for success in teaching (States et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2015). See the section Personal Competencies, below.

Formative Assessment

Also called progress monitoring, formative assessment is a tool that teachers use to monitor student progress; it focuses on learning goals, gauging where students’ current work is in relation to the goal, and taking action to progress toward the goal (Brookhart, 2010). To use formative assessment effectively, teachers must be able to assess student performance, display and analyze data, and use their judgment to develop remedial interventions based on that data (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1986).

The research on the size of formative assessment’s impact on learning is mixed (Hattie, 2009; Kingston & Nash, 2011). Across multiple meta-analyses, the effect sizes ranged from small, at 0.2 (Kingston & Nash, 2011) to large, at 0.9 (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1986; Hattie, 2008) and 1.09 (Scheerens & Bosker, 1997). In the first quantitative analysis of formative assessment, Fuchs and Fuchs (1986) found that the full impact came from teachers collecting data (0.26), graphing it (0.7) and then analyzing it using a structured procedure (0.9).

In the classroom, collecting weekly progress monitoring data produced medium (0.7) to large (0.91) effect sizes (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1986). To get the most out of formative assessment, teachers should be taught how to collect and analyze data weekly (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1986; Haller et al., 1988; Hattie, 2009; Yeh, 2007).

In today’s classrooms, formative assessment often occurs in larger systemic interventions, like Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS), so teacher candidates must learn how to execute a range of assessments and use the data to support classroom and schoolwide interventions (Hattie, 2009; Marzano et al., 2001). Additional research on how teachers currently use formative assessment and the effect in typical classroom settings is necessary to understand how teachers use these tools and to solidify more best practices for teacher preparation programs.

Classroom Management

Classroom management skills are a prerequisite for creating a classroom where students can learn. The ability to effectively manage a classroom reduces behavior problems and has a moderate effect size (0.521) on student learning and achievement (Marzano et al., 2003). Because classroom management is also a consistent area of concern for school administrators and teachers, it is an important area of focus for teacher preparation programs (Everston & Weinstein, 2013).

Greenberg et al. (2014) reviewed 150 studies spanning six decades and identified the “big five” classroom management strategies for new teachers:

- Rules: Establish and teach classroom rules that communicate expectations for behavior.

- Routines: Build structure and routines to guide students in a variety of situations.

- Praise: Reinforce positive behavior.

- Interventions: Consistently impose consequences for misbehavior.

- Engagement: Foster and maintain student engagement by teaching interesting lessons with opportunities for student participation.

Rules and routines. Having rules and procedures in place is important in establishing a classroom where students can learn, a concept supported in the research. When classroom rules and routines were applied systematically, teachers’ active monitoring of behavior, or classroom management was associated with a 20% increase in student achievement (Hattie, 2009).

When classrooms are highly structured through rules and routines, students are more on-task and their behavior is more attentive (Simonsen et al., 2008). Structure includes the physical arrangement of space, minimized distractions, and an appropriate balance of teacher-directed and student-directed tasks.

Praise. Simonsen et al. (2008) identified specific, contingent praise as “a positive statement, typically provided by the teacher, when a desired behavior occurs to inform students specifically what they did well” (p. 362). There are various ways to provide students with praise, including individual praise, group reinforcement contingencies given to a group when an expectation is met, behavior contracts, and token economies.

Praise is a simple yet powerful strategy with a strong foundation in research (Simonsen et al., 2008). Delivering contingent praise in a school setting increased the amount of desired behavior, whether that was academic performance or completion of classwork (Ferguson & Houghton, 1992; Sutherland et al., 2000).

Behavior-specific praise, or stating a desired behavior paired with praise (e.g., “You did a great job writing your words. I can tell you have been practicing), reinforces behavior that a student can control (Royer et al., 2019). Praise is also a behavior intervention that can be delivered individually or to a group, and verbally, written, or in another way, depending on the student and situation (Haydon & Musti-Rao, 2011; Houghton et al., 1990).

Even though praise is a simple strategy to implement, teacher candidates should be taught how to deliver praise and should receive feedback on their use of praise while teaching. Myers et al. (2011) found that some teachers required additional support to deliver behavior-specific praise effectively.

Interventions to address misbehavior. Just as teachers must acknowledge students’ positive behavior, they must also address behavior that disrupts the learning environment. These interventions include strategies to reduce behavior disruptions (Wing Institute, 2021). There are key strategies that reduced the likelihood that an inappropriate behavior would continue.

- Error correction: When a negative behavior occurs, provide an informative statement that tells the student what to do in the future.

- Performance feedback: Provide information to a student about a target behavior, a goal for that behavior, and a reward if the goal is met.

- Differential reinforcement: Provide reinforcement when a student engages in low rates of a negative behavior, a positive behavior, or an alternative behavior.

- Planned ignoring: Withhold attention from a misbehaving student who is seeking attention.

- Response cost: Remove a stimulus when a student engages in a negative behavior.

- Time-out from reinforcement: Remove a student from an environment that provides positive reinforcement, either by removing the student or removing the element that is reinforcing (Alberto & Troutman, 2006; Cooper et al., 2007).

Positive teacher-student rapport. Positive relationships are another key to learning. One way to explicitly foster such relationships is for teachers to provide positive and timely feedback for appropriate behavior and respond consistently to inappropriate behavior (Simonsen et al., 2008). An easy way to do this to greet students at the classroom door. Cook et al. (2018) showed that providing positive greetings improved the time that middle school students spent engaged in academics and reduced disruptive behavior.

What Do Teachers Candidates Learn About Classroom Management During Their Training?

What teacher candidates learn about classroom management matters. Goodson et al. (2019) surveyed more than 3,000 teachers about what they had learned in teacher training. Teachers who reported more experiences in creating a productive learning environment than in promoting analytical thinking skills were more effective in the classroom, as measured by higher student test scores.

Although most teacher preparation programs claim to address classroom management, unfortunately not many have incorporated it effectively. Greenberg et al. (2014) found that in 122 teacher preparation programs, the instruction and application of classroom management strategies were scattered across the curriculum rather than being the focus of one class. The practice of spreading classroom management skills across the program did not produce coherent instruction and application of classroom management. As Greenberg and colleagues noted, “Embedding training everywhere is a recipe for having effective training nowhere” (p. ii).

There were no programs that identified classroom management as a priority, effectively taught classroom management using research-based strategies, and provided teacher candidates with feedback. Most programs did not draw from research to decide what to teach; for example, programs asked candidates to develop their own philosophy of classroom management rather than teaching evidence-based practices. In many programs, instruction was separate from practice and vice versa; there was little evidence that what was taught was practiced. Only one third of programs required teacher candidates to practice classroom management skills. This disconnect extended into student teaching (Greenberg et al., 2014). [End sidebar]

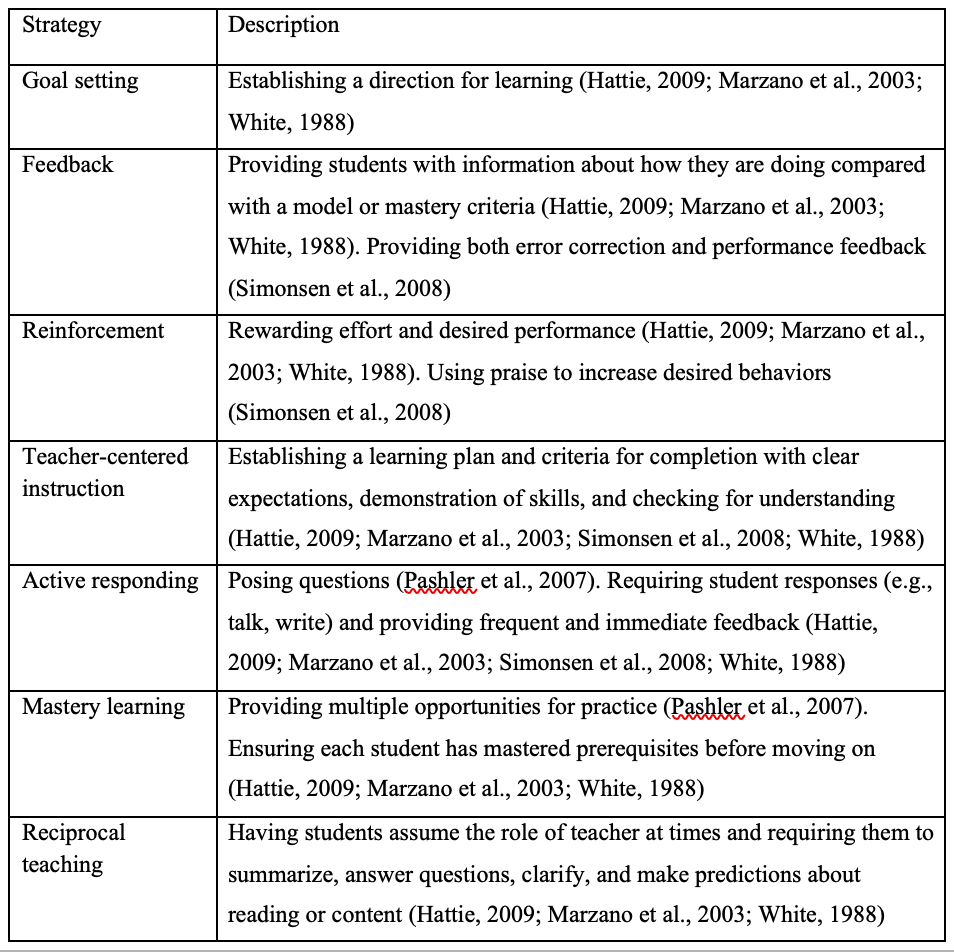

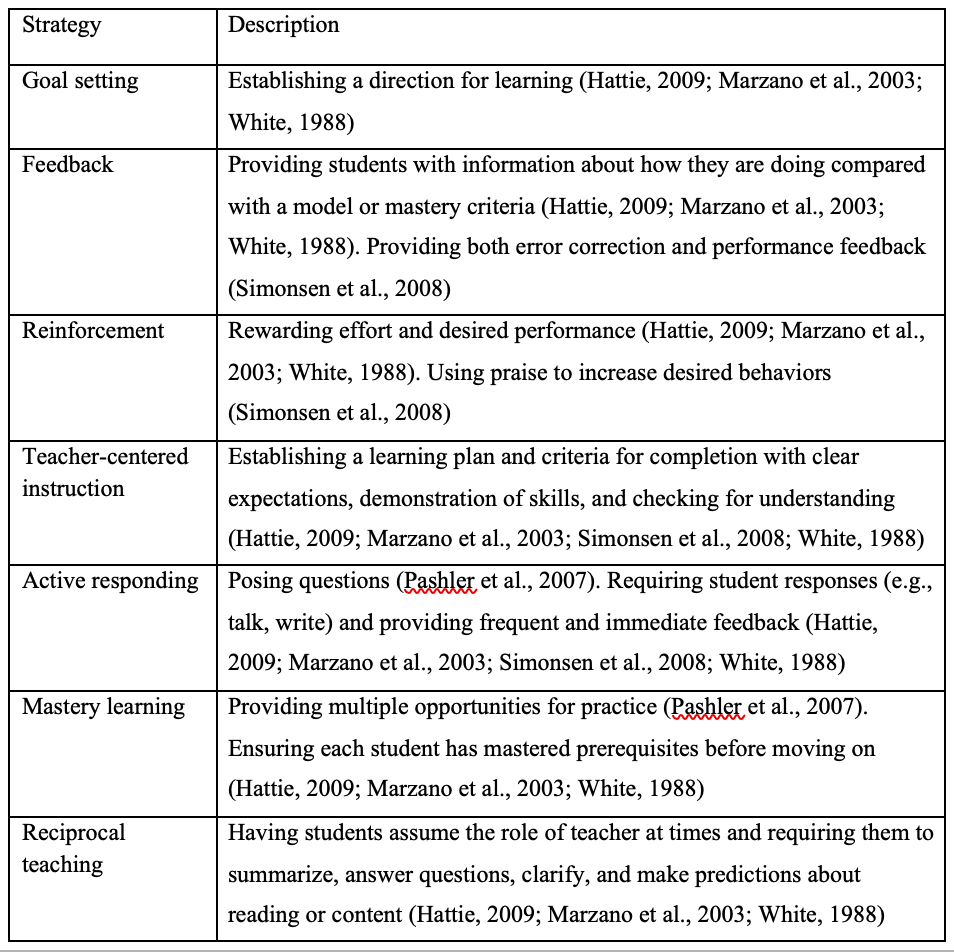

Teaching Strategies

Teaching strategies, or instructional strategies, are how teachers teach. Hattie (2009) found a moderate effect size (0.6) for teaching strategies. Marzano (1998) also found a moderate effect size (0.52). Teacher candidates need to learn the instructional strategies that are most effective (Table 1).

Table 1

Teaching strategies

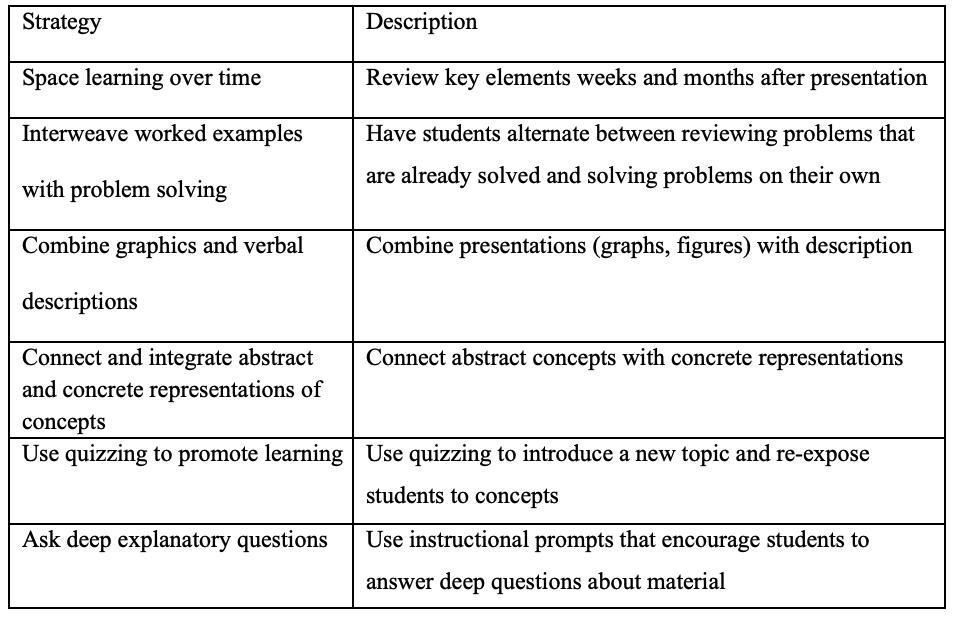

Pashler et al. (2007) identified six core ways teachers can organize learning based on research evidence (Table 2).

Table 2

Teaching strategies with moderate to strong evidence (Pashler et al., 2007)

Pomerance et al. (2016) outlined six practices found to be effective in helping students learn. Six overarching strategies that are grouped into various themes:

- Strategies that help students take in new information:

- o Pairing graphics with words and

- o Connecting abstract concepts with concrete representations.

- Strategies that help students connect information to deepen understanding:

- o Posing questions (why, how, what if, and how do you know) and

- o Providing problems for students to solve.

- Strategies to help students remember what they have learned:

- o Making sure students practice material several times after learning, and

- o Using assessments that require students to recall material.

How many of these strategies teacher candidates are learning is unclear. Pomerance et al. (2016) reviewed 48 textbooks used in elementary and secondary teacher education programs because textbooks often drive what teacher candidates learn about how to teach. They found that no textbooks accurately described and addressed all the strategies. At most, two strategies were addressed. The strategy that was most frequently addressed was questioning.

Explicit instruction. A research-based approach to teaching, explicit instruction includes structured and systematic teaching that emphasizes mastery of the lesson to ensure student understanding. It builds from small to larger ideas with a focus on mastering foundational content before applying it.

When teachers use explicit instruction, they do the following (Archer & Hughes, 2011; Knight, 2012):

- Select the learning area to teach and set a criterion for success.

- Inform students of the criterion prior to the lesson.

- Model the successful use of knowledge or skills.

- Assesses or evaluate student learning.

- Provide support or remediation.

- Provide a closure at the end of the lesson.

To deliver effective explicit instruction, teachers must be able to do the following (Archer & Hughes, 2011; Knight, 2012):

- Prepare well-designed lessons that move students from one level of knowledge to another. This involves having clear objectives, scope, and sequence to teach the range of skills in an order that progresses sequentially.

- Plan instruction that provides sufficient opportunities for practice.

- Plan instruction that provides enough time for students to master the material.

Teaching reading. All teachers should know how to effectively teach students to read (Drake & Walsh, 2020; Giles et al., 2013). Despite concerns that nearly two-thirds of fourth graders read below grade level, and this has remained consistent over time (Rea, 2020), teachers often reported leaving teacher preparation without a strong understanding of the core aspects of reading instruction (Will, 2019).

The National Reading Panel (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [NICHHD], 2000) identified five aspects of reading that impact student success: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. These five components along with the use of explicit instruction to teach them are often called the science of reading. Teachers should be trained in how to teach these five aspects of reading (Hattie, 2009).

The National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ; Drake & Walsh, 2020) surveyed university undergraduate programs in 2013 and 2020; it assigned scores to assess how much and how well the programs taught the science of reading. Teacher preparation programs that earned an A taught the five aspects of reading through coursework and textbooks. Lectures and discussion included explicit instruction in the five components and teacher candidates were required to demonstrate mastery of the concepts through teaching activities, not just assessments. In 2020, more than half of teacher preparation programs taught the science of reading with an A or B rating, compared with 35% in 2013 (Drake & Walsh, 2020). Undergraduate programs were twice as likely to teach the science of reading compared with graduate programs and 4 times as likely as alternative certification programs (Drake & Walsh, 2020). However, there were gaps in the aspects that teacher candidates learned about; teacher preparation programs were more likely to include instruction in how to teach phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension. Only 51% of programs provided instruction in how to teach phonemic awareness, a foundational reading skill, and only 53% spent provided instruction on fluency.

Implementing a well-designed curriculum

The curriculum is what teachers teach. It is unreasonable to require teachers to be trained in every available curriculum. However, teachers can be trained in how to deliver instruction in core areas using research-based methods (NICHHD, 2000). And they can be trained in how to deliver instruction using strategies that are common across multiple curricula. One way to look at this is to think about kernels, or core behaviors, that have been found reliable and necessary (Embry & Biglan, 2008). For example, being able to deliver explicit instruction can be a kernel skill in teaching a variety of different topics. Other kernel behaviors in education could be including active student responding, providing immediate feedback, and promoting self-monitoring. All of those behaviors can be used to teach content from reading to science. Teacher candidates can be trained to look for kernels in thinking about how to administer the content of each curriculum.

In short, teachers can be taught aspects of curriculum that we know are effective (e.g., those included in What Works Clearinghouse database). And they can be taught which methods are ineffective, for example, whole language, so they can avoid them (Hattie, 2009).

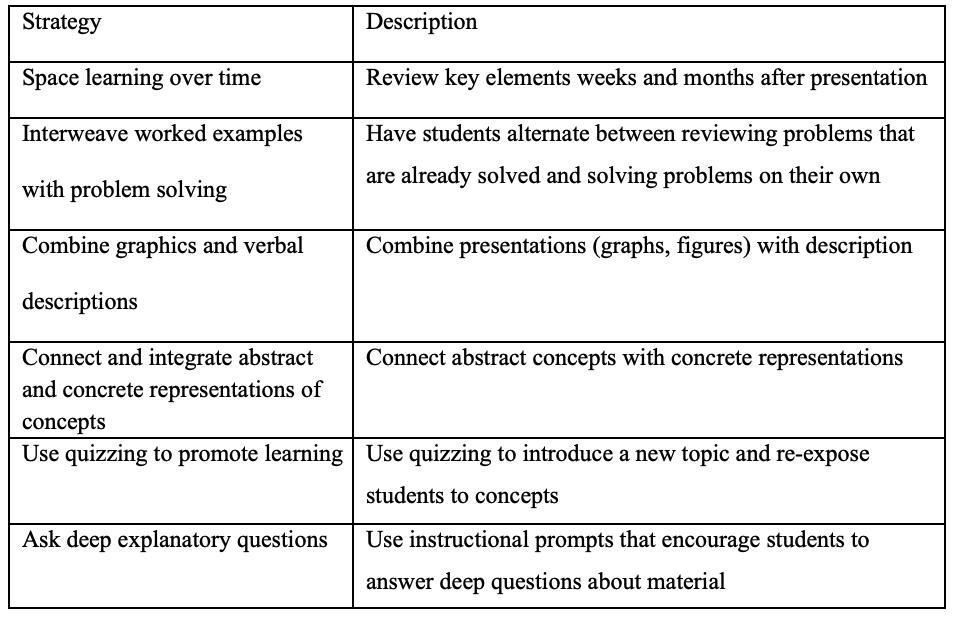

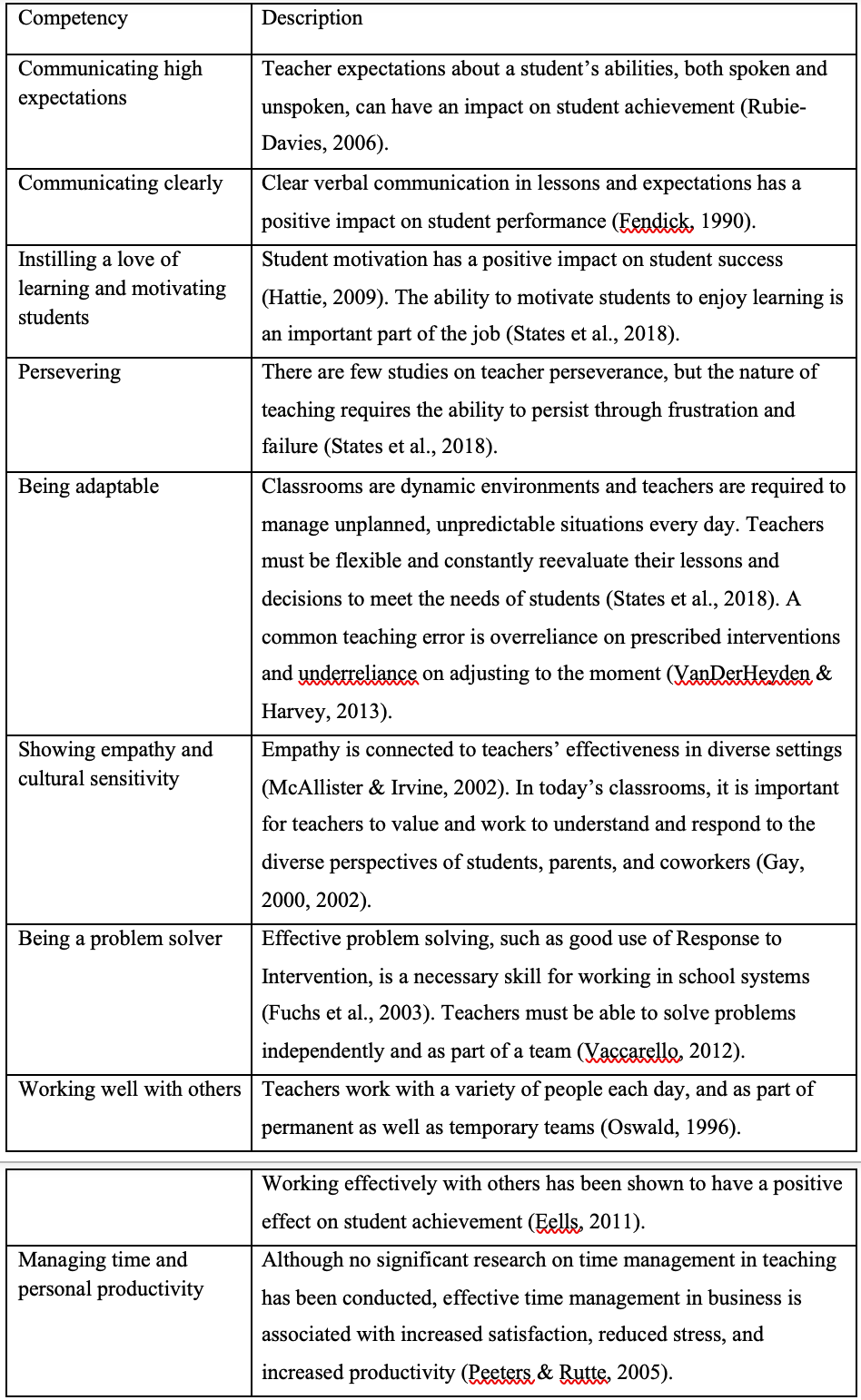

Personal Competencies

The things that teachers do to help students in their classrooms—their people management skills—are known as personal competencies, or soft skills. They include the following (Attakorn et al., 2014):

- Establishing high yet achievable expectations

- Encouraging a love of learning

- Listening

- Being flexible and adaptable

- Showing empathy

- Displaying cultural sensitivity

- Having a positive regard for students

These personal skills promote teacher-student relationships, which improve student achievement and classroom climate (Cornelius-White, 2007; Marzano, et al., 2003). Soft skills have also been linked to effective teaching (see Table 3).

To some degree, personal competencies cannot be taught and may even be technically the same from teacher to teacher but with differing results in the classroom (e.g., two teachers may show empathy, even though the students of one have higher achievement scores than the other; Matteson et al., 2016). Perhaps the most important thing that soft skills do is help teachers develop relationships with their students; large effect sizes (0.72 to 0.87) have been reported for the impact of positive teacher-student relationships on student achievement (Cornelius-White, 2007; Marzano et al., 2003) and moderate effect sizes on classroom behavior (0.52; Hattie, 2009).

Table 3

Personal competencies

Teaching Diverse Classrooms

Today’s teachers must be prepared to address the needs of increasingly diverse classrooms. This involves understanding the diversity of students in terms of abilities, interests, and response to various situations. It also involves applying teaching strategies and managing a classroom with student diversity in mind. Despite an increase in teaching about diverse learners in teacher preparation programs, knowledge about how to develop teacher capacity to teach diverse learners is still being developed (Rahman et al., 2010).

One specific area of diversity that teachers will encounter is ability. The majority of students with disabilities learn in the general education classroom (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020). Teacher preparation programs must cover how to teach students with an Individual Education Program (IEP) or 504 Plan. Most teacher preparation programs include instruction in this area. A majority of programs (73% of elementary school and 67% of secondary school) require at least one course in supporting students with disabilities (Government Accountability Office, 2009). Even so, a 2019 teacher survey found that most general education teachers did not feel prepared to successfully teach students with disabilities (Mitchell, 2019).

The number of students who do not speak English at home is also increasing and teachers will likely teach students with linguistic diversity (Mitchell, 2020). They may not feel prepared to teach these students—a feeling expressed by 24 teachers at a rural elementary school in North Carolina (O’Neal et al., 2008).

Is There Alignment Between What Districts Want in New Teachers and What Teacher Preparation Programs Teach?

The goal of training is to produce teachers who can effectively lead classrooms. However, the training that teachers receive and what districts need may not align. For example, Greenberg and Walsh (2012) found a misalignment in terms of assessment and use of data. Specifically, districts require teachers who can understand and utilize a range of classroom and standardized test data, while what teacher candidates learned about assessment did not align with what districts were using.

The evidence indicates that what is taught in teacher preparation programs does not always align with what teachers need to know to be successful from their first day in the classroom. Teacher preparation programs did not always effectively integrate and teach evidence-based classroom management (Greenberg et al., 2014). Teacher preparation programs did not universally teach all five aspects of the science of reading (Drake & Walsh, 2020), and teachers reported feeling unprepared to teach reading (Will, 2019). Also, teachers indicated that they felt unprepared to meet the needs of students with disabilities (Mitchell, 2019). More research is needed on exactly what teacher candidates need, especially in terms of using technology and teaching diverse classes.

Recommendations for Curriculum Content

Teacher preparation programs should focus on teaching those variables that have been shown to influence student achievement: classroom management, formative assessment, teaching strategies, implementing well-designed curriculum (Hattie, 2009; Kavale, 2005; States et al., 2012; Wang et al., 1997). They should also focus on preparing teachers for the job of teaching in today’s schools by teaching soft skills and preparing teachers to teach diverse learners.

Classroom Management

Greenberg et al. (2014) set out the following recommendations:

- Prepare teachers to use research-based classroom management strategies starting in foundational courses and continuing through their training, including student teaching.

- Collect data from school administrators and use it to refine and develop coursework around classroom management. Input from principals can help develop what teacher candidates are learning so that they have the skills to address a school’s current needs.

- Make sure that teacher candidates receive instruction and application in the “big five” classroom management: rules and routines, praise, interventions to address misbehavior, and engagement.

- Use videos of real teachers dealing with behavior concerns to expose teacher candidates to more examples than they could experience on their own.

- Use in-class simulations that allow teacher candidates to practice classroom management strategies.

- Have teacher candidates reflect on the specific strategies they are using rather than reflect generally about classroom management.

- Provide teacher candidates with feedback on their classroom management and use of strategies from cooperating teachers or university supervisors, or both. This requires cooperating teachers selected to work with teacher candidates during student teaching to have strong classroom management skills and to use research-based strategies.

Teachers should also be taught to use evidence-based practices. Those that increase positive behaviors and reduce negative behaviors, such as praise, error correction, and differential reinforcement, are especially important (Cooper et al., 2007; Simonsen et al., 2008).

Formative Assessment

Formative assessment should be collected and analyzed regularly to help teachers effectively make decisions about student learning. Teachers should be taught how to use formative assessment data to provide feedback to students and advance student learning (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1986). In particular, teachers should be taught how to use formative assessment data in ways that are relevant to the type of data that they will be using in classrooms.

Instructional Strategies

In short, teachers should be trained to implement research-based strategies (Hattie, 2009; Marzano et al., 2003; Pashler, 2007; White, 1988). These strategies include goal setting, feedback, reinforcement, teacher-centered strategies, active responding, mastery learning, and reciprocal teaching (Hattie, 2009; Marzano et al., 2003; White, 1988) as well as explicit instruction (Archer & Hughes, 2011; Knight, 2012).

Teacher preparation programs should choose textbooks that incorporate research-based strategies (Pomerance et al., 2016). These include strategies that help students take in new information, connect and deepen understanding, and remember what they have learned (Pashler, 2007). In addition, preparation programs must avoid textbooks promoting instructional strategies that are not supported by research or have weak research support.

Finally, teacher candidates should be well versed in the science of reading (NICHHD, 2000).

Curriculum

While learning every available curriculum is unreasonable, teachers should be trained in how to implement instruction using research-based methods (NICHHD, 2000). Teacher candidates should also be taught how to identify and avoid strategies that are ineffective, for example, whole language instruction (Hattie, 2009).

Personal Competencies

Personal competencies, or soft skills, can be taught to and supported in teacher candidates:

- Building relationships with students, which will improve student achievement and classroom climate (Cornelius-White, 2007; Marzano et al., 2003). One method is to train teachers to support positive communication by maintaining a ratio of 4 to 5 positive interactions with students for every negative interaction (Gable et al., 2009; Kalis et al., 2007).

- Communicating high expectations for students and identifying any biases that could negatively impact student performance (Rubie-Davies, 2006)

- Developing adaptability by reflecting on how to use knowledge to adjust to various situations

- Building problem-solving skills, both in the classrooms and the broader school system (Fuchs et al., 2003; Vaccarello, 2012)

- Working in teams

- Managing time well in the context of actual teaching

Additional Recommendations

Teacher preparation programs should use information from districts to ensure they are teaching skills that teachers will need. For example, teacher preparation programs could collect data about what assessments are given and how the data is used to better prepare teacher candidates to manage formative assessment in today’s classrooms (Greenberg & Walsh, 2012).

Teacher preparation programs should develop strong partnerships with local schools and support bringing together teachers across curriculum areas, bilingual education, English language learners, and special education.

Teacher candidates should be taught how to address the needs of diverse classrooms (Rahman et al., 2010). This means that general education teacher training programs must prepare teachers to teach students with disabilities as well as English language learners (Smith, 2020).

Conclusion

The content that teacher candidates learn during their time in teacher preparation programs is important for their ability to teach effectively from the start of their careers. Focusing on research-based practices in high-leverage skills, including formative assessment, classroom management, and instructional strategies, as well as cultivating personal competencies will best prepare teacher candidates for success in the classroom. Furthermore, collaborating with school leaders to align curriculum content with what districts need in teachers will support successful teaching and learning.

Citations

Alberto, P. A., & Troutman, A. C. (2006). Applied behavior analysis for teachers (7th ed.). Pearson.

Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Explicit instruction: Efficient and effective teaching. Guilford Press.

Attakorn, K., Tayut, T., Pisitthawat, K., & Kanokorn, S. (2014). Soft skills of new teachers in the secondary schools of Khon Kaen Secondary Educational Service Area 25, Thailand. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 1010–1013.

Brookhart, S. M. (2010). Formative assessment strategies for every classroom: An ASCD action tool (2nd ed.). ASCD. http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/111005/chapters/Section-1@-What-Is-Formative-Assessment¢.aspx

Cochran-Smith, M., & Villegas, A. M. (2015). Studying teacher preparation: The questions that drive research. European Educational Research Journal, 14(5), 379–394.

Cook, C. R., Fiat, A., Larson, M., Daikos, C., Slemrod, T., Holland, E. A., Thayer, A. J., & Renshaw, T. (2018). Positive greetings at the door: Evaluation of a low-cost, high-yield proactive classroom management strategy. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(3), 149–159.

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). Pearson/Merrill-Prentice Hall.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143.

Drake, G., & Walsh, K. (2020). 2020 teacher prep review: Program performance in early reading instruction. National Council on Teacher Quality. https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/NCTQ_2020_Teacher_Prep_Review_Program_Performance_in_Early_Reading_Instruction

Eells, R. J. (2011). Meta-analysis of the relationship between collective teacher efficacy and student achievement[Doctoral dissertation, Loyola University Chicago]. Loyola eCommons, 133. https://ecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1132&context=luc_diss

Embry, D. D., & Biglan, A. (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11(3), 75–113.

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. Routledge.

Fendick, F. (1990). The correlation between teacher clarity of communication and student achievement gain: A meta-analysis [Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville]. https://archive.org/details/correlationbetwe00fend/page/n0

Ferguson, E., & Houghton, S. (1992). The effects of contingent teacher praise, as specified by Canter’s Assertive Discipline programme on children’s off-task behavior. Educational Studies, 18(1), 83–93.

Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D., (1986). Effects of systematic formative evaluation: A meta-analysis. Exceptional Children, 53(3), 199–208.

Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Prentice, K., Burch, M., Hamlett, C. L., Owen, R., & Schroeter, K. (2003). Enhancing third-grade students’ mathematical problem solving with self-regulated learning strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 306–315.

Gable, R. A., Hester, P. H., Rock, M. L., Hughes, K. G. (2009). Back to basics: Rules, praise, ignoring, and reprimands revisited. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(4), 195–205.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106–116.

Giles, R. M., Kent, A. M., & Hiberts, M. (2013). Investigating preservice teachers’ sense of reading efficacy. The Reading Professor, 35(1), 18–24.

Goldhaber, D. (2016). In school, teacher quality matters most. Education Next, 16(2), 56–62. https://www.educationnext.org/in-schools-teacher-quality-matters-most-coleman/

Goodson, B., Caswell, L., Price, C., Litwok, D., Dynarski, M., Crowe, E., Meyer, R., & Rice, A. (2019). Teacher preparation experiences and early teacher effectiveness (NCEE 2019-4007). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20194007/pdf/20194007.pdf

Government Accountability Office. (2009). Teacher preparation: Multiple federal education offices support teacher preparation for instructing students with disabilities and English language learners, but systematic departmentwide coordination could enhance this assistance (GAO-09-573). https://www.gao.gov/assets/300/294197.pdf

Greenberg, J., Putnam, H., & Walsh, K. (2014). Training our future teachers: Classroom management. National Council on Teacher Quality. https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/Future_Teachers_Classroom_Management_NCTQ_Report

Greenberg, J. & Walsh, K. (2012). What teacher preparation programs teach about K–12 assessment: A review.National Council on Teacher Quality. https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/What_Teacher_Prep_Programs_Teach_K-12_Assessment_NCTQ_Report

Haller, E. P., Child, D. A., & Walberg, H. J. (1988). Can comprehension be taught? A quantitative synthesis of “metacognitive” studies. Educational Researcher, 17(9), 5–8.

Hattie, J., (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses related to achievement. Routledge.

Haydon, T., & Musti-Rao, S. (2011). Effective use of behavior-specific praise: A middle school case study. Beyond Behavior, 20(2), 31–39.

Holdheide, L. (2020, August 5). Promising strategies to prepare new teachers in a COVID-19 world. American Institutes for Research. https://www.air.org/resource/promising-strategies-prepare-new-teachers-covid-19-world

Houghton, S., Wheldall, K., Jukes, R., & Sharpe, A. (1990). The effects of limited private reprimands and increased private praise on classroom behaviour in four British secondary school classes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 60(3), 255–265.

Kalis, T. M., Vannest, K. J., & Parker, R. (2007). Praise counts: Using self-monitoring to increase effective teaching practices. Preventing School Failure, 51(3), 20–27.

Kavale, K. A. (2005). Effective intervention for students with specific learning disability: The nature of special education. Learning Disabilities, 13(4), 127–138.

Kingston, N., & Nash, B. (2011). Formative assessment: A meta-analysis and a call for research. Educational Measurement Issues and Practice, 30(4), 28–37. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2011.00220.x

Klein, A. (2018, July 16). Does ESSA require teachers to be highly qualified? Education Week.https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/does-essa-require-teachers-to-be-highly-qualified/2018/07

Knight, J. (2012). High-impact instruction: A framework for great teaching. Corwin Press.

Marzano, R. J. (1998). A theory-based meta-analysis of research on instruction. McREL International.

Marzano, R. J., Marzano, J. S., & Pickering, D. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research-based strategies for every teacher. ASCD.

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D., & Pollock, J. E. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. ASCD.

Matteson, M. L., Anderson, L., & Boyden, C. (2016). “Soft skills”: A phrase in search of meaning. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 16(1), 71–88.

McAllister, G., & Irvine, J. J. (2002). The role of empathy in teaching culturally diverse students: A qualitative study of teachers’ beliefs. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(5), 433–443.

Mitchell, C. (2019, May 29). Most classroom teachers feel unprepared to support students with disabilities. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/most-classroom-teachers-feel-unprepared-to-support-students-with-disabilities/2019/05

Mitchell, C. (2020, February 18). The nation’s English-learner population has surged: 3 Things to know. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/the-nations-english-learner-population-has-surged-3-things-to-know/2020/02

Myers, D. M., Simonsen, B., & Sugai, G. (2011). Increasing teachers’ use of praise with a response-to-intervention approach. Education and Treatment of Children, 34(1), 35–59.

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. U.S.C. § 6319 (2008).

National Center for Education Statistics. (2020, May). Students with disabilities.https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: Reports of the subgroups (00-4754). U.S. Government Printing Office.

O’Neal, D. D., Ringler, M., & Rodriguez, D. (2008). Teachers’ perceptions of their preparation for teaching linguistically and culturally diverse learners in rural eastern North Carolina. The Rural Educator, 30(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v30i1.456

Oswald, L. J. (1996). Work teams in schools. ERIC Digest, 103.

Pashler, H., Bain, P., Bottge, B., Graesser, A., Koedinger, K., McDaniel, M., & Metcalfe, J. (2007). Organizing instruction and study to improve student learning (NCER 2007-2004). National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED498555.pdf

Peeters, M. A., & Rutte, C. G. (2005). Time management behavior as a moderator for the job demand-control interaction. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(1), 64–75.

Pomerance, L., Greenberg, J., & Walsh, K. (2016). Learning about learning: What every new teacher needs to know.National Council on Teacher Quality. www.nctq.org/dmsView/Learning_About_Learning_Report

Rahman, F. A., Scaife, J. Yahya, N. A. & Jalil, H. A. (2010). Knowledge of diverse learners: Implications for the practice of teaching. International Journal of Instruction, 3(2), 83–96. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED522935

Ravitch, D. (2003, August 23). A brief history of teacher professionalism. U. S. Department of Education, White House Conference on Preparing Tomorrow’s Teachers. https://www2.ed.gov/admins/tchrqual/learn/preparingteachersconference/ravitch.html

Rea, A. (2020, April 29). How serious is America’s literacy problem? Library Journal. https://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=How-Serious-Is-Americas-Literacy-Problem

Roca, J. V., & Gross, A. M. (1996). Report-do-report: Promoting setting and setting-time generalization. Education and Treatment of Children, 19(4), 408–424.

Royer, D. J., Lane, K. L., Dunlap, K. D., & Ennis, R. P. (2019). A systematic review of teacher-delivered behavior-specific praise on K–12 student performance. Remedial and Special Education, 40(2), 112–128.

Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2006). Teacher expectations and student self-perceptions: Exploring relationships. Psychology in the Schools, 43(5), 537–552.

Scheerens, J., & Bosker. R. J. (1997). The foundations of educational effectiveness. Pergamon.

Simonsen, B., Fairbanks, S, Briesch, A. Myers, D., & Sugai, G. (2008). Evidence-based practices in classroom management: Considerations for research to practice. Education and Treatment of Children, 31(3), 351–380. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236785368_Evidence-based_Practices_in_Classroom_Management_Considerations_for_Research_to_Practice/link/575802c208ae04a1b6b9a5ba/download

Smith, V. (2020, January 23). How teacher preparation programs can help all teachers better serve students with disabilities. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/news/2020/01/23/479675/teacher-preparation-programs-can-help-teachers-better-serve-students-disabilities/

States, J., Detrich, R., & Keyworth, R. (2012). Effective teachers make a difference. In R. Detrich, R. Keyworth, & J. States (Eds.), Advances in evidence-based education: Vol. 2. Education at the crossroads: The state of teacher preparation (pp. 1–45). The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/uploads/docs/Vol2Ch1.pdf

States, J., Detrich, R., & Keyworth, R. (2018). Overview of teacher soft skills. The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/teacher-compentencies-soft-skills

Sutherland, K. S., Webby, J. H., & Copeland, S. R. (2000). Effect of varying rates of behavior-specific praise on the on-task behavior of students with EBD. Journal of Emotional and Behavior Disorders, 8(1), 2–8.

Tang, K. N., Yunus, H. M., & Hashim, N. H. (2015). Soft skills integration in teaching professional training: Novice teachers’ perspectives. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 186, 835–840

Vaccarello, C. A. (2012). Effects of a problem solving team intervention on the problem-solving process: Improving concept knowledge, implementation integrity, and student outcomes [Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin–Madison]. https://www.winginstitute.org/uploads/docs/Cara%20Vaccarello%20Dissertation%20Final%20Deposit-1.pdf

VanDerHayden, A., & Harvey, M. (2013). Using data to advance learning outcomes in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15(4), 205–213.

Wang, M., Haertel, G., & Walberg H. (1997) Learning influences. In H. Walberg & G. Haertel (Eds.), Psychology and educational practice (pp. 199–211). McCutchan Publishing.

White, W. A. T. (1988). A meta-analysis of the effects of direct instruction in special education. Education and Treatment of Children, 11(4), 364–374.

Will, M. (2019, December 3). Will the science of reading catch on in teacher prep? Education Week.https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/will-the-science-of-reading-catch-on-in-teacher-prep/2019/12

Wing Institute. (2021). Effective instruction overview. https://www.winginstitute.org/effective-instruction-overview

Yeh, S. S. (2007). The cost-effectiveness of five policies for improving student achievement. American Journal of Evaluation, 28(4), 416–436.