Decreasing Inappropriate Behavior Overview

Decreasing Inappropriate Behavior PDF

Guinness, K., Detrich, R., Keyworth, R. & States, J. (2020). Overview of Decreasing Inppropriate Behavior. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/classroom-inappropriate-behaviors.

Introduction

Inappropriate classroom behavior includes calling out, disruption, not following directions, aggression, and property destruction. In this overview, the terms “inappropriate behavior,” “disruptive behavior,” “challenging behavior,” and “problem behavior” are used interchangeably to describe the wide variety of behaviors that are undesirable in the classroom. Inappropriate behavior is challenging for teachers; multiple studies have demonstrated the relationship between high levels of disruptive classroom behavior and teacher stress and burnout (e.g., Friedman-Krauss, Raver, Morris, & Jones, 2014; Hastings & Bham, 2003).

Exclusionary practices such as suspension and expulsion are unlikely to decrease inappropriate behavior. Massar, McIntosh, and Eliason (2015) found that more than half of middle school students who were suspended at the beginning of the school year received at least one more suspension during the school year. Further, exclusionary practices can be disproportionally applied to students who belong to minority groups (Sprague, 2018). Examining research on effective methods for decreasing inappropriate behavior is key for establishing a school-wide system that addresses inappropriate behavior consistently to ensure success for all students.

The first step in decreasing disruptive behavior is to increase appropriate behavior (seeSupporting Appropriate Behavior). Responding effectively when disruptive behavior occurs is also critical to decrease disruptive behavior. Incorporating proactive strategies to increase appropriate behavior as well as effective responses to disruptive behavior is characteristic of the universal tier[C1] of a multitiered system of support (see Multitiered System of[KG2] Support). For students who engage in persistent disruptive behavior even with universal interventions in place, additional assessment and more individualized intervention are warranted. This overview describes strategies for how school personnel can respond when disruptive behavior occurs, including (1) negative consequences that can be applied as primary interventions, (2) functional behavior assessment, and (3) function-based, individualized interventions characteristic of the secondary or tertiary tiers of a multitiered system of support.

Negative Consequences for Disruptive Behavior

When disruptive behavior occurs, teachers can respond in a number of ways, including reprimands, time-outs, and response cost. These strategies are negative consequences or procedures to decrease inappropriate behavior in the future.

Reprimand

A reprimand is a statement of disapproval delivered when challenging behavior occurs (e.g., “Don’t do that”). In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, researchers explored the use of reprimands in classrooms. Some studies demonstrated that reprimands decreased disruptive behavior (Hall et al., 1971). In addition, specific characteristics of how the reprimands were delivered increased their effectiveness. Van Houten, Nau, MacKenzie-Keating, Sameoto, and Colavecchia (1982) found that reprimands delivered with eye contact were more effective than those without eye contact, and reprimands made in close proximity (1 meter away) to the student were more effective than those delivered at a distance (7 meters away). O’Leary, Kaufman, Kass, and Drabman (1970) found that reprimands delivered so only the individual student could hear (soft reprimands) were more effective than reprimands delivered so other students could hear (loud reprimands). In contrast, Thomas, Becker, and Armstrong (1968) found that reprimands increased disruptive behavior. These discrepant results could be due to the fact that reprimands are effective for some students but not others.

More recently, multiple studies have sought to increase teachers’ praise-to-reprimand ratio (Caldarella, Larsen, Williams, Wills, & Wehby, 2019; Rathel, Drasgow, Brown, & Marshall, 2014). Although a number of ratios (3:1, 4:1, 5:1) have been recommended, there is limited empirical support for a “magic ratio” of praise to reprimands (Sabey, Charlton, & Charlton, 2019). However, there is strong support for the use of praise (see Supporting Appropriate Behavior) to increase appropriate behavior.

Mild reprimands (e.g., “Be quiet,” “No running”) can be appropriate in the universal tier, but caution is also warranted when considering an intervention involving reprimands. A particular concern is that reprimands can increase disruptive behavior by providing the student with attention, even if the attention is negative. Attention in some form is a common consequence for inappropriate behavior (Thompson & Iwata, 2001, 2007). Therefore, placing an emphasis on providing attention for appropriate behavior is recommended as an alternative to reprimands.

Time-Out

Another negative consequence that can decrease disruptive behavior is a time-out. When challenging behavior occurs, the student loses the opportunity to access positive reinforcement. Time-outs can be nonexclusionary or exclusionary. A nonexclusionary time-out deprives the student of the opportunity to earn positive reinforcement without removing the student from the classroom environment; for example, contingent observation or “sit and watch.” The student who engages in challenging behavior is required to sit away from the group and watch others participate, then rejoins the group after a specified period of time. White and Bailey (1990) described how this procedure substantially decreased disruptive behavior in a physical education class.

An exclusionary time-out removes the student from the environment, such as sending the student to sit in the hallway. It should be noted that this form of time-out is considerably more intrusive and difficult to implement (e.g., escorting the student to the time-out location). Therefore, this form of time-out should be considered only in the tertiary tier after other options have been exhausted.

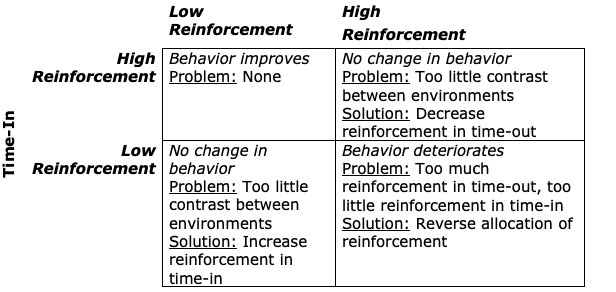

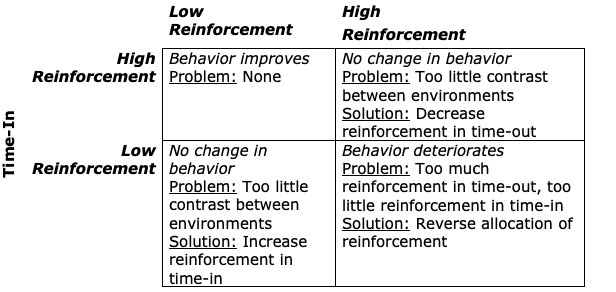

For a time-out to be effective, there must be a contrast between the time-out and the time-in environment. The time-in environment is rich with positive reinforcement, while the time-out environment limits reinforcement. Shriver and Allen (1996) created a time-out grid highlighting this important contrast and provided overall recommendations for effective time-outs:

- Enrich the time-in environment. The time-out will not be effective if the environment the student is removed from is not reinforcing.

- Separate the student from reinforcement to the degree possible and limit attention.

- Keep it short. Make a time-out between 30 seconds and 4 minutes; no research has shown that longer time-outs are more effective.

- Release from a time-out can come after a certain amount of time regardless of the student’s behavior, or it can come after a certain amount of time of quiet, appropriate behavior. More recently, researchers found that requiring a period of appropriate behavior before release from a time-out did not have additional benefits over a fixed-duration time-out (Donaldson & Vollmer, 2011).

Time-Out

Time-out grid adapted from Shriver and Allen (1996)

Although a nonexclusionary time-out could be considered a universal intervention, caution is still recommended. Another important consideration in using a time-out is the function of the disruptive behavior that results in the time-out (see “Determining the Function of Behavior,” below). If the behavior occurs because the student wants to escape work or the classroom environment, a time-out may increase disruptive behavior. Taylor and Miller (1997) determined that two students were engaging in disruptive behavior to escape work. They found that time-outs increased disruptive behavior while working through (prompting the student to complete work) decreased disruptive behavior.

Response Cost

Response cost involves removing a specific amount of positive reinforcement when disruptive behavior occurs. For example, Nolan and Filter (2012) provided music to a student with ADHD noncontingently and removed the music when self-stimulatory behavior occurred, resulting in a decrease in this behavior. Another example is the response cost lottery or raffle: The teacher places a fixed number of tickets on the students’ desks at the beginning of the lesson and removes tickets when challenging behavior occurs. At the end of the lesson, students enter any remaining tickets into a raffle for prizes (Proctor & Morgan, 1991; Witt & Elliot, 1982).

Response cost is practical and easy to add to an existing reinforcement system. It is important to note, however, that the reinforcement system alone may be effective without response cost (e.g., Jurbergs, Palcic, & Kelley, 2007; McGoey & DuPaul, 2000). Therefore, reinforcement procedures without response cost should be tried first, and response cost considered only if reinforcement alone is not effective. Moreover, Tanol, Johnson, McComas, and Cote (2010) directly compared the Good Behavior Game implemented with reinforcement versus response cost. The Good Behavior Game involves dividing the class into two or more teams, providing points to the teams based on appropriate behavior, and the team with the most points earning a reward (see Supporting Appropriate Behavior for a more thorough description of the Good Behavior Game). In Tanol et al.’s study, the reinforcement variation involved students starting the day with no stars and earning stars for appropriate behavior; the response cost variation involved students starting the day with four stars and losing stars for inappropriate behavior. Both versions had similar effects, including reducing disruptive behavior and increasing appropriate behavior, but teachers reported they preferred the reinforcement variation.

Ultimately, if reinforcement and response cost procedures produce similar effects, reinforcement procedures are more consistent with a model of positive behavioral supports. Therefore, reinforcement procedures are preferable to response cost as a primary intervention. Response cost can be incorporated as a tier 2 or tier 3 intervention if reinforcement procedures alone are not effective.

Function-Based Interventions

Strategies for increasing appropriate behavior and decreasing inappropriate behavior should be incorporated into the universal tier of a multitiered system of support. Students who continue to engage in disruptive behavior even when universal strategies are in place may require additional support in the form of more individualized interventions. The first step in developing an individualized intervention is determining why the behavior is occurring.

Inappropriate Behavior Happens for a Reason

Inappropriate behavior occurs to get individuals something they want or need. In other words, every behavior serves a function (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). Common functions of behavior include attention, escape, items/activities, and sensory.

Attention. Attention can come from a variety of sources (teachers, peers) and can take a variety of forms (praise, assistance). Even negative attention (e.g., “Don’t do that”) can be reinforcing for some students.

Escape. Escape from something the student does not like is another common function of challenging behavior. The student may seek to escape from work or tasks, from attention (i.e., to be left alone), or from an undesirable environment (e.g., a noisy classroom).

Items/Activities. Students can also engage in disruptive behavior to access physical items that they want or need, such as food or toys. This function also encompasses access to movement (e.g., the freedom to move around the room instead of sitting at a desk) or specific activities.

Sensory. Disruptive behavior sometimes occurs because the behavior itself feels good. Everyone engages in sensory behavior to some degree; examples include humming, foot tapping, and nail biting. Students with developmental or intellectual disabilities may engage in stereotypy (e.g., hand flapping, rocking, noncontextual vocalizations), which is most often reported to be sensory in nature (DiGennaro Reed, Hirst, & Hyman, 2012). This function also can involve the removal of unpleasant sensory stimulation (e.g., scratching an itch, covering ears to muffle loud noise).

Combinations of Reasons for Inappropriate Behavior

Attention, escape, items/activities, and sensory can be considered the four basic functions of behavior but, in the real world, each rarely appears in isolation. Challenging behavior can arise from a combination of functions. For example, a student makes an inappropriate comment during a math lesson. The other students in the class laugh, and the teacher sends the student to sit in the hall. The reason the student made the inappropriate comment could be for peer attention, to escape the math lesson, or a combination of the two.

How the behavior looks does not necessarily suggest why it is happening, and the same behavior can serve different functions for different students. For example, Broussard and Northup (1995) conducted functional assessments of three students who engaged in disruptive classroom behavior. They found that although the behaviors looked similar across the three students, the functions of the behavior varied: teacher attention for one student, peer attention for another student, and escape from work for the third student. Therefore, additional information beyond the form of the behavior is needed to determine the function of behavior.

Determining the Function of Behavior

Functional behavior assessment (FBA) refers to a variety of assessment strategies that involve observing the environment in which the challenging behavior occurs to identify potential reasons for the behavior (Anderson, Rodriguez, & Campbell, 2015; Cooper et al., 2007). In some cases, conducting an FBA may be legally required under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; see Collins & Zirkel, 2017, for a discussion of the legal and professional requirements surrounding FBAs).

Conducting an FBA requires specialized training, and attempting to identify the function of an inappropriate behavior may be challenging for teachers. Youngbloom and Filter (2013) found considerable variability in the skills of pre-service teachers in identifying behavior function based on video vignettes. However, because teachers often have the most knowledge of the circumstances under which disruptive behavior occurs, their role in the FBA process is essential. Multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy of coaching teachers to conduct FBAs as part of an interdisciplinary team (e.g., Pence, St. Peter, & Giles, 2014; Rispoli et al., 2015).

FBAs may be conducted as part of the intensive tier of a multitiered system of support. For example, Trussell, Lewis, and Raynor (2016) evaluated the effects of universal teacher practices (including providing instructions, allowing a wait time of 3 seconds for students to respond, providing prompts, and maintaining a 4:1 ratio of praise to negative feedback) and FBA-based interventions on the challenging behavior of three elementary school students. The universal practices resulted in moderate decreases in disruptive behavior by the three students. However, because these decreases were not considered socially significant, FBAs were conducted and function-based interventions developed. These individualized interventions resulted in greater, socially significant decreases in disruptive behavior.

Function-Based Interventions

Function-based interventions involve choosing how to respond to challenging behavior based on why it is happening. Multiple studies have demonstrated that function-based interventions result in greater improvements than non-function-based interventions (Ellingson, Miltenberger, Stricker, Galensky, & Garlinghouse, 2000; Ingram, Lewis-Palmer, & Sugai, 2005). Iwata, Pace, Cowdery, & Miltenberger (1994) highlighted the necessity of determining function when utilizing interventions based on extinction (see discussion below). If the function is not accurately identified, the intervention may be counterproductive. For example, a student yells to access teacher attention. In a non-function-based intervention, the teacher pulls the student aside and explains that yelling is disruptive to the other students. This intervention provides the student with attention for yelling, which will likely increase the behavior. Alternatively, a function-based intervention ignores yelling and provides attention for appropriate behavior. Yelling will likely decrease because it does not get the student what he or she wants whereas appropriate behavior does.

A study by Trussell et al. (2016) highlighted how interventions can be individualized for each student based on the function of the challenging behavior. For two participants whose behaviors were maintained by attention, the intervention called for providing immediate attention for appropriate behavior and withholding attention for inappropriate behavior. One participant’s behavior was maintained by escape from work; the intervention provided opportunities to take breaks when work was completed appropriately. Notably, the intervention for each student was customized based on the students’ motivation, and involved strategies to decrease challenging behavior as well as reinforcement for appropriate behavior.

Noncontingent reinforcement

One type of function-based intervention is noncontingent reinforcement (NCR). It involves identifying why the challenging behavior is occurring, then periodically providing what the student wants, regardless of the student’s behavior (Coy & Kostewicz, 2018). For example, if a student engages in calling out for attention, NCR has the teacher provide attention to the student regularly throughout the day.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of NCR. Austin and Soeda (2008) determined that the off-task behavior of two third graders was maintained by access to teacher attention. The intervention consisted of teachers providing attention every 4 minutes; the researchers used a MotivAider (a small electronic device worn by the teacher that provides vibratory cues) to remind teachers to do this. To deal with disruptive behavior maintained by access to peer attention, a study by Jones, Drew, and Weber (2000) called for a peer to provide attention noncontingently, which reduced disruptive behavior.

NCR can also be implemented for behaviors that occur to escape work. Waller and Higbee (2010) provided participants with noncontingent breaks, which reduced disruptive behavior and increased appropriate academic behavior. In addition, after the initial success of NCR, the researchers gradually decreased the number and duration of the breaks, so the students accessed more academic time while maintaining low levels of disruptive behavior.

Extinction-Based Interventions

Another type of function-based intervention is extinction, which is employed after identifying why the behavior is happening. Extinction involves changing the environment so the inappropriate behavior no longer produces the desired result. If applied consistently, extinction results in a decrease in the challenging behavior over time. It is extremely important to withhold the reinforcer every time the behavior occurs. If extinction is not implemented consistently, it is unlikely to be effective and may even make the behavior worse (Cooper et al., 2007).

Planned Ignoring. The teacher withholds attention (talking to, looking at the student) when challenging behavior occurs. Therefore, the challenging behavior no longer produces the result of attention.

It is crucial that teachers ignore the specific disruptive behavior of students, not the students themselves. As soon as a student engages in appropriate behavior, the teacher should provide attention (Hester, Hendrickson, & Gable, 2009).

Planned ignoring should be used in combination with other strategies to increase appropriate alternative behavior. For example, Schumate and Wills (2010) determined that the disruptive behavior of three elementary school students occurred to access teacher attention. The intervention called for the teacher to provide attention periodically when disruptive behavior was not occurring, provide attention when students raised their hands, and withhold attention when disruptive behavior occurred.

Planned ignoring, when combined with providing attention for appropriate behavior, can be utilized as a universal strategy (tier 1 intervention), as well as part of an intervention package in tier 2 or 3 supports.

Escape Extinction. Escape extinction is an intervention to address challenging behavior related to escape from work or other undesirable environments. When challenging behavior occurs, the teacher does not remove the task.

Guided compliance or tell-show-help is an effective strategy to increase following directions. The teacher tells the student to complete the task (e.g., “Open your book”). If the student does not follow the direction, the teacher shows the student how to complete the task (e.g., “Open your book like this”—the teacher models opening a book). If the student still does not follow the direction, the teacher helps the student complete the task (e.g., the teacher guides the student’s hands to open the book). The effectiveness of guided compliance has been demonstrated with young children (Cote, Thompson, & McKerchar, 2005; Wilder & Atwell, 2006) and has been found to enhance the effectiveness of other interventions, such as providing reinforcement for compliance (Wilder, Myers, Nicholson, Allison, & Fischerti, 2012).

It is important to note that guided compliance is only practical to implement with younger students and with instructions that can be prompted by physically moving the students’ hands. Guided compliance would likely be used in tier 3 as it requires considerable individualization and one-on-one implementation.

Escape extinction can also be implemented without hand-over-hand guidance. In a study by Wright-Gallo, Higbee, Reagon, and Davey (2006), FBAs revealed that the two participants engaged in disruptive behavior to access attention and escape from work. The intervention involved teaching the students to appropriately request attention or a break from work. If disruptive behavior occurred, the teacher provided a brief instruction to “get back on task,” but did not provide further attention or a break from work.

Escape extinction is an intensive intervention that is challenging to implement. It also can produce a number of undesirable side effects (see the next section). Therefore, escape extinction should be considered only in the intensive tier in a multitiered system of support after other options have been explored.

Side Effects of Extinction-Based Interventions

Extinction-based interventions can produce the following undesirable side effects (Cooper et al., 2007):

- Getting worse before getting better. The inappropriate behavior may increase in frequency or intensity (e.g., louder yelling) when extinction is first implemented.

- Trying something different. Students may engage in new forms of inappropriate behavior because their original behavior is not working to get what they want.

- Emotional behavior. Students may cry or engage in other emotional responses.

Important Considerations for Behavior Reduction Procedures

- Beware of undesirable side effects. Negative consequences can potentially harm the teacher-student relationship. The student may become withdrawn or begin to avoid the teacher delivering the negative consequence. Also, the teacher may be inclined to overuse negative consequences if they result in an immediate cessation of inappropriate behavior (Cooper et al., 2007). For example, if a teacher shouts “Be quiet!” and talking immediately stops, the teacher is more likely to shout the same command in the future. Negative consequences may involve modeling undesirable behavior for students (Cooper et al., 2007). For example, if a teacher yells, the students may attempt to imitate the teacher, leading to additional inappropriate behavior.

Extinction-based interventions, in particular, can be difficult to implement and produce a number of side effects such as an initial increase in disruptive behavior, emergence of new disruptive behavior, and emotional behavior.

- Try positive strategies first. Using strategies based on reinforcement to increase appropriate behavior first before considering additional behavior reduction strategies is consistent with a multitiered system of support. Further, some reinforcement-based interventions may be just as effective if not more effective than interventions incorporating negative consequences or extinction (e.g., Jurbergs et al., 2007; McGoey & DuPaul, 2000; Tanol et al., 2010).

- Increase an appropriate alternative. Behavior reduction strategies should never be implemented in isolation. When decreasing an inappropriate behavior, always identify an appropriate replacement behavior to increase; this teaches the student what to do in addition to what not to do. A replacement behavior should serve the same function as the inappropriate behavior. For example, if yelling functions to access teacher attention, the replacement behavior (e.g., appropriate requesting, tapping on the shoulder) should also access teacher attention.

Teaching appropriate replacement behavior can also help to mitigate the side effects associated with these interventions. Lerman, Iwata, and Wallace (1999) found that side effects of extinction (e.g., increase in disruptive behavior, new forms of disruptive behavior) were less likely to occur when interventions also included reinforcement for appropriate behavior than when extinction was applied alone.

Conclusions and Implications

Decreasing inappropriate behavior is vital to creating a positive school environment where all students can learn. The first step in decreasing inappropriate behavior is supporting appropriate behavior (see Supporting Appropriate Behavior). However, responding effectively when challenging behavior occurs is another critical component of interventions to decrease the behavior. Applying negative consequences such as reprimands, time-outs, or response cost can reduce the occurrence of challenging behavior in the future.

For students who continue to engage in disruptive behavior with universal strategies in place (i.e., a combination of reinforcement for appropriate behavior and negative consequences for challenging behavior), additional support may be needed. Determining the function, or why the behavior is happening, prior to implementing an intervention allows for the selection of the most effective intervention. Disruptive behavior can occur for a number of reasons and the same behavior may function differently for different students (Broussard & Northup, 1995; Iwata et al., 1994; Trussell et al., 2016). Strategies based on the function of the student’s behavior are more effective than non-function-based interventions (Ellingson et al., 2000; Ingram et al., 2005; Taylor & Miller, 1997)

Function-based interventions to decrease challenging behavior include NCR and extinction-based interventions. NCR involves providing the student with what they want (e.g., attention, escape from work) periodically throughout the day regardless of the student’s behavior. Extinction-based interventions involve identifying why the behavior is happening, then changing the environment so the behavior no longer produces that result, and include planned ignoring and guided compliance or working through.

Side effects such as an initial increase in inappropriate behavior, new forms of disruptive behavior, or emotional behavior can occur with extinction-based interventions. Negative consequences can also produce side effects, such as student withdrawal, teacher overuse, and undesirable modeling. Combining behavior reduction procedures with reinforcement for appropriate behavior mitigates these side effects, teaches students what to do in addition to what not to do, and aligns with a system of positive behavioral support.

Citations

Anderson, C. M., Rodriguez, B. J., & Campbell, A. (2015). Functional behavior assessment in schools: Current status and future directions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 24(3), 338–371. doi: 10.1007/s10864-015-9226-z

Austin, J. L., & Soeda, J. M. (2008). Fixed-time teacher attention to decrease off-task behaviors of typically developing third graders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(2), 279–283. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-279

Broussard, C. D., & Northup, J. (1995). An approach to functional assessment and analysis of disruptive behavior in regular education classrooms. School Psychology Quarterly, 10(2), 151–164. doi: 10.1037/h0088301

Caldarella, P., Larsen, R. A. A., Williams, L., Wills, H. P., & Wehby, J. H. (2019). Teacher praise-to-reprimand ratios: Behavioral response of students at risk for EBD compared with typically developing peers. Education and Treatment of Children, 42(4), 447–468.

Collins, L. W., & Zirkel, P. A. (2017). Functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans: Legal requirements and professional recommendations. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions, 19(3), 180–190. doi: 10.1177/1098300716682201

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Cote, C. A., Thompson, R. H., & McKerchar, P. M. (2005). The effects of antecedent interventions and extinction on toddlers’ compliance during transitions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38(2), 235–238. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.143-04

Coy, J. N., & Kostewicz, D. E. (2018). Noncontingent reinforcement: Enriching the classroom environment to reduce problem behaviors. Teaching Exceptional Children, 50(5), 301–309.

DiGennaro Reed, F. D., Hirst, J. M., & Hyman, S. R. (2012). Assessment and treatment of stereotypic behavior in children with autism and other developmental disabilities: A thirty year review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.07.003

Donaldson, J. M., & Vollmer, T. R. (2011). An evaluation and comparison of time-out procedures with and without release contingencies. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(4), 693–705. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-693

Ellingson, S. A., Miltenberger, R. G., Stricker, J., Galensky, T. L., & Garlinghouse, M. (2000). Functional assessment and intervention for challenging behaviors in the classroom by general classroom teachers. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(2), 85–97. doi: 10.1177/109830070000200202

Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Raver, C. C., Morris, P. A., & Jones, S. M. (2014). The role of classroom-level child behavior problems in predicting preschool teacher stress and classroom emotional climate. Early Education and Development, 25(4), 530–552.

Hall, R., Axelrod, S., Foundopoulos, M., Shellman, J., Campbell, R., & Cranston, S. (1971). The effective use of punishment to modify behavior in the classroom. Educational Technology, 11(4), 24–26.

Hastings, R. P., & Bham, M. S. (2003). The relationship between student behaviour patterns and teacher burnout. School Psychology International, 24(1), 115–127.

Hester, P. P., Hendrickson, J. M., & Gable, R. A. (2009). Forty years later: The value of praise, ignoring, and rules for preschoolers at risk for behavior disorders. Education and Treatment of Children, 32(4), 513–535. doi: 10.1353/etc.0.0067

Ingram, K., Lewis-Palmer, T. & Sugai, G. (2005). Function-based intervention planning: Comparing the effectiveness of FBA function-based and non-function-based intervention plans. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7(4), 224–236. doi: 10.1177/10983007050070040401

Iwata, B. A., Pace, G. M., Cowdery, G. E., & Miltenberger, R. G. (1994). What makes extinction work: An analysis of procedural form and function. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(1), 131–144. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27–131

Jones, K. M., Drew, H. A., & Weber, N. L. (2000). Noncontingent peer attention as treatment for disruptive classroom behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33(3), 343–346.

Jurbergs, N., Palcic, J., & Kelley, M. L. (2007). School-home notes with and without response cost: Increasing attention and academic performance in low-income children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(3), 358–379. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.22.3.358

Lerman, D. C., Iwata, B. A., & Wallace, M. D. (1999). Side effects of extinction: Prevalence of bursting and aggression during the treatment of self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-1

Massar, M. M., McIntosh, K., & Eliason, B. M. (2015). Do out-of-school suspensions prevent further exclusionary discipline? PBIS evaluation brief. Eugene, OR: OSEP Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports.

McGoey, K. E., & DuPaul, G. J. (2000). Token reinforcement and response cost procedures: Reducing the disruptive behavior of preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Quarterly, 15(3), 330–343. doi: 10.1037/h0088790

Nolan, J. D., & Filter, K. J. (2012). A function-based classroom behavior intervention using non-contingent reinforcement plus response cost. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(3), 419–430.

O’Leary, K. D., Kaufman, K. F., Kass, R. E., & Drabman, R. S. (1970). The effects of loud and soft reprimands on the behavior of disruptive students. Exceptional Children, 37(2), 145–155.

Pence, S. T., St. Peter, C. C., & Giles, A. F. (2014). Teacher acquisition of functional analysis methods using pyramidal training. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23(1), 132–149. doi: 10.1007/s10864-013-9182-4

Proctor, M. A., & Morgan, D. (1991). Effectiveness of a response cost raffle procedure on the disruptive classroom behavior of adolescents with behavior problems. School Psychology Review, 20(1), 97.

Rathel, J. M., Drasgow, E., Brown, W. H., & Marshall, K. J. (2014). Increasing induction-level teachers’ positive-to-negative communication ratio and use of behavior-specific praise through e-mailed performance feedback and its effect on students’ task engagement. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 16(4), 219–233. doi:10.1177/1098300713492856

Rispoli, M., Burke, M. D., Hatton, H., Ninci, J., Zaini, S., & Sanchez, L. (2015). Training Head Start teachers to conduct trial-based functional analysis of challenging behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17(4), 235–244. doi: 10.1177/1098300715577428

Sabey, C. V., Charlton, C., & Charlton, S. R. (2019). The “magic” positive-to-negative interaction ratio: Benefits, applications, cautions, and recommendations. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 27(3), 154-164. doi: 10.1177/1063426618763106

Schumate, E. D., & Wills, H. P. (2010). Classroom-based functional analysis and intervention for disruptive and off-task behaviors. Education and Treatment of Children, 33(1), 23–48.

Shriver, M. D., & Allen, K. D. (1996). The time-out grid: A guide to effective discipline. School Psychology Quarterly, 11(1), 67–74.

Sprague, J. R. (2018). Closing in on discipline disproportionality: We need more theoretical, methodological, and procedural clarity. School Psychology Review, 47(2), 196–198. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2018-0017.V47-2

Tanol, G., Johnson, L., McComas, J., & Cote, E. (2010). Responding to rule violations or rule following: A comparison of two versions of the Good Behavior Game with kindergarten students. Journal of School Psychology, 48(5), 337–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.06.001

Taylor, J., & Miller, M. (1997). When timeout works some of the time: The importance of treatment integrity and functional assessment. School Psychology Quarterly, 12(1), 4–22.

Thomas, D. R., Becker, W. C., & Armstrong, M. (1968). Production and elimination of disruptive classroom behavior by systematically varying teacher’s behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 35–45. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-35

Thompson, R. H., & Iwata, B. A. (2001). A descriptive analysis of social consequences following problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(2), 169–178. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-169

Thompson, R. H., & Iwata, B. A. (2007). A comparison of outcomes from descriptive and functional analyses of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(2), 333–338. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.56-06

Trussell, R. P., Lewis, T. J., & Raynor, C. (2016). The impact of universal teacher practices and function-based behavior interventions on the rates of problem behavior among at-risk students. Education and Treatment of Children, 39(3), 261–282.

Van Houten, R., Nau, P. A., MacKenzie-Keating, S. E., Sameoto, D., & Colavecchia, B. (1982). An analysis of some variables influencing the effectiveness of reprimands. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 15(1), 65–83. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1982.15-65

Waller, R. D., & Higbee, T. S. (2010). The effects of fixed-time escape on inappropriate and appropriate classroom behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(1), 149–153. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-149

White, A. G., & Bailey, J. S. (1990). Reducing disruptive behaviors of elementary physical education students with sit and watch. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23(3), 353–359. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-353

Wilder, D. A., & Atwell, J. (2006). Evaluation of a guided compliance procedure to reduce noncompliance among preschool children. Behavioral Interventions, 21(4), 265–272. doi: 10.1002/bin.222

Wilder, D. A., Myers, K., Nicholson, K., Allison, J., & Fischerti, A. T. (2012). The effects of rationales, differential reinforcement, and a guided compliance procedure to increase compliance among preschool children. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(1), 111–122. doi: 10.1353/etc.2012.0005

Witt, J. C., & Elliott, S. N. (1982). The response cost lottery: A time efficient and effective classroom intervention. Journal of School Psychology, 20(2), 155–161.

Wright-Gallo, G. L., Higbee, T. S., Reagon, K. A., & Davey, B. J. (2006). Classroom-based functional analysis and intervention for students with emotional/behavioral disorders. Education and Treatment of Children, 29(3). 421–436.

Youngbloom, R. & Filter, K. J. (2013). Pre-service teacher knowledge of behavior function: Implications within the classroom. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 11(3), 631–648. doi: 10.14204/ejrep.31.13063

TITLE

SYNOPSIS

CITATION

LINK

Mystery motivator: An effective and time efficient intervention.

Systematically applied W. R. Jenson's (1990, unpublished; see also G. Rhode et al, 1992) Mystery Motivator (MM) across 9 Ss (5 3rd-grade boys and 4 5th-grade boys) from 2 classrooms.

Moore, L. A., Waguespack, A. M., Wickstrom, K. F., Witt, J. C., et al. (1994). Mystery motivator: An effective and time efficient intervention. School Psychology Review, 23(1), 106–118.

Extrinsic Reinforcement in the Classroom: Bribery or Best Practice

The debate over the effects of the use of extrinsic reinforcement in classrooms, businesses, and societal settings has been occurring for over 30 years. This article examines the debate with an emphasis on data-based findings. The extrinsic/intrinsic dichotomy is explored along with seminal studies in both the cognitive and behavioral literature.

Akin-Little, K. A., Eckert, T. L., Lovett, B. J., & Little, S. G. (2004). Extrinsic reinforcement in the classroom: Bribery or best practice. School Psychology Review, 33(3), 344-362.

Applied behavior analysis for teachers

Scholarly and empirically based, this market-leading text gives students what they need to understand using the principles and practices of applied behavioral management in the classroom. The book covers: identifying target behavior, collecting and graphing data, functional assessment, experimental design, arranging antecedents and consequences, generalizing behavior change and discusses the importance of ethical considerations in using applied behavior analysis in the classroom.

Alberto, P., & Troutman, A. C. (2006). Applied behavior analysis for teachers (pp. 1-474). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

Effects of teacher greetings on student on-task behavior.

A multiple baseline design across participants was used to determine how teacher greetings affected on‐task behavior of 3 middle school students with problem behaviors.

Allday, R. A., & Pakurar, K. (2007). Effects of teacher greetings on student on-task behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(2), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2007.86-06

Applying Positive Behavior Support and Functional Behavioral Assessments in Schools

The purposes of this article are to describe (a) the context in which PBS and FBA are needed and (b) definitions and features of PBS and FBA.

applying positive behavior support

Using differential reinforcement of low rates to reduce children’s requests for teacher attention

We evaluated the effectiveness of full-session differential reinforcement of low rates of behavior (DRL) on 3 primary school children's rates of requesting attention from their teacher. Using baseline rates of responding and teacher recommendations, we set a DRL schedule that was substantially lower than baseline yet still allowed the children access to teacher assistance.

Austin, J. L., & Bevan, D. (2011). Using differential reinforcement of low rates to reduce children's requests for teacher attention. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 44(3), 451-461.

Effects of immediate and delayed error correction on the acquisition and maintenance of sight words by students with developmental disabilities

We compared immediate and delayed error correction during sight-word instruction with 5 students with developmental disabilities. Whole-word error correction immediately followed each error for words in the immediate condition. In the delayed condition, whole-word error correction was provided at the end of each session's three practice rounds. Immediate error correction was superior on each of the four dependent variables.

Barbetta, P. M., Heward, W. L., Bradley, D. M., & Miller, A. D. (1994). Effects of immediate and delayed error correction on the acquisition and maintenance of sight words by students with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(1), 177-178.

Good behavior game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom.

The present study investigated the effects of a classroom behavior management technique based on reinforcers natural to the classroom, other than teacher attention.

Barrish, H. H., Saunders, M., & Wolf, M. M. (1969). Good behavior game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom 1. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 2(2), 119-124.

Decreasing excessive bids for attention in a simulated early education classroom

Differential-reinforcement-of-low-rate (DRL) schedules can be used to decrease, but not eliminate, excessive bids for teacher attention in a classroom. There are two primary methods of implementing a DRL: full session and spaced responding.

Becraft, J. L., Borrero, J. C., Mendres-Smith, A. E., & Castillo, M. I. (2017). Decreasing excessive bids for attention in a simulated early education classroom. Journal of Behavioral Education, 26(4), 371-393.

Reducing severe aggressive and self-injurious behaviors with functional communication training.

Functional communication training incorporates a comprehensive assessment of the communicative functions of maladaptive behavior with procedures to teach alternative and incompatible responses.

Bird, F., Dores, P. A., Moniz, D., & Robinson, J. (1989). Reducing severe aggressive and self-injurious behaviors with functional communication training. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 94(1), 37-48.

Nine Competencies for Teaching Empathy.

The author shares nine teachable competencies that can serve as a principal's guide for empathy education. This paper will help answer which practices enhance empathy and how will principals know if teachers are implementing them effectively.

Borba, M. (2018). Nine Competencies for Teaching Empathy. Educational Leadership, 76(2), 22-28.

Blueprints for Violence Prevention, Book Five: Life Skills Training

This volume describes research aimed at identifying 10 model programs proven effective for violence prevention; describes the 10 programs selected from the more than 400 reviewed; and details the goals, targeted risk and protective factors, design, and other aspects of Life Skills Training, one of the model programs selected.

Botvin, G. J., Mihalic, S. F., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1998). Blueprints for violence prevention: Book five: Life skills training. Boulder, CO: Center for Study and Prevention of Violence.

Promoting Positive Behavior Using the Good Behavior Game: A Meta-Analysis of Single-Case Research

This meta-analysis synthesized single-case research (SCR) on The Good Behavior Game across 21 studies, representing 1,580 students in pre-kindergarten through Grade 12.

Bowman-Perrott, L., Burke, M. D., Zaini, S., Zhang, N., & Vannest, K. (2016). Promoting positive behavior using the Good Behavior Game: A meta-analysis of single-case research. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(3), 180-190.

A state-wide partnership to promote safe and supportive schools: The PBIS Maryland initiative

This paper summarizes an approach to prevention partnerships developed over a decade and centered on the three-tiered Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) model.

Bradshaw, C. P., Pas, E. T., Bloom, J., Barrett, S., Hershfeldt, P., Alexander, A., ... & Leaf, P. J. (2012). A state-wide partnership to promote safe and supportive schools: The PBIS Maryland initiative. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(4), 225-237.

Effects of School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports on Child Behavior Problems

The current study reports intervention effects on child behaviors and adjustment from an effectiveness trial of School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports.

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & Leaf, P. J. (2012). Effects of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior problems. Pediatrics, 130(5), e1136-e1145.

Further investigation of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without extinction for escape-maintained destructive behavior

Previous research indicates that manipulating dimensions of reinforcement during differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) for situations in which extinction cannot be implemented is a potential approach for treating destructive behavior.

Briggs, A. M., Dozier, C. L., Lessor, A. N., Kamana, B. U., & Jess, R. L. (2019). Further investigation of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without extinction for escape‐maintained destructive behavior. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 52(4), 956-973.

Strategies and tactics for promoting generalization and maintenance of young children's social behavior

Employing a conceptual framework of generalization strategies proposed by Stokes and Osnes (1986), the authors selectively reviewed the research literature concerning interventions to improve young children's social behavior and strategies for promoting generalization and maintenance of young children's social responding. Three basic strategies are discussed.

Brown, W. H., & Odom, S. L. (1994). Strategies and tactics for promoting generalization and maintenance of young children's social behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 15(2), 99-118.

A randomized trial of case management for youths with serious emotional disturbance

Reports on a randomized trial of case management carried out in conjunction with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Mental Health Services Program for Youth in North Carolina (RWJ MHSPY).

Burns, B. J., Farmer, E. M., Angold, A., Costello, E. J., & Behar, L. (1996). A randomized trial of case management for youths with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(4), 476-486.

Pervasive Negative Effects of Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation: The Myth Continues

The purpose of the present article is to resolve differences in previous meta-analytic findings and to provide a meta-analysis of rewards and intrinsic motivation that permits tests of competing theoretical explanations.

Cameron, J., Banko, K. M., & Pierce, W. D. (2001). Pervasive negative effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation: The myth continues. The Behavior Analyst, 24(1), 1-44.

Enhancing Effects of Check-in/Check-out with Function-Based Support

The authors evaluating effects of a school's implementation of check-in/check-out with two typically developing students in the school.

Campbell, A., & Anderson, C. M. (2008). Enhancing effects of check-in/check-out with function-based support. Behavioral Disorders, 33(4), 233-245.

Positive practice overcorrection: The effects of duration of positive practice on acquisition and response reduction

The effects of long and short durations of positive practice overcorrection were studied, for the reduction of off-task behavior after an instruction to perform an object-placement task.

Carey, R. G., & Bucher, B. (1983). Positive practice overcorrection: The effects of duration of positive practice on acquisition and response reduction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 16(1), 101-109.

Reducing Behavior Problem Through Functional Communication

It is generally agreed that serious misbehavior in children should be replaced with socially appropriate behaviors, but few guidelines exist with respect to choosing replacement behaviors. The authors address this issue in two experiments.

Carr, E. G., & Durand, V. M. (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 18(2), 111-126.

Positive Behavior Support: Evolution of an Applied Science

This article (a)provide a definition of the evolving applied science of positive behavior support (PBS); (b)describe the background sources from which PBS has emerged; (c)give an overview of the critical features that, collectively, differentiate PBS from other approaches; and (d) articulate a vision for the future of PBS.

Carr, E. G., Dunlap, G., Horner, R. H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A. P., Sailor, W., ... & Fox, L. (2002). Positive behavior support: Evolution of an applied science. Journal of positive behavior interventions, 4(1), 4-16.

Comprehensive Multisituational Intervention for Problem Behavior in the Community: Long-Term Maintenance and Social Validation

Assessment and intervention approach for dealing with problem behavior need to be extended so that they can be effectively and comprehensively applied within the community. To meet assessment needs, the authors developed a three-component strategy: description, categorization, and verification.

Carr, E. G., Levin, L., McConnachie, G., Carlson, J. I., Kemp, D. C., Smith, C. E., & McLaughlin, D. M. (1999). Comprehensive multisituational intervention for problem behavior in the community: Long-term maintenance and social validation. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1(1), 5-25.

Performance Feedback and Teachers' Use of Praise and Opportunities to Respond: A Review of the Literature

This review of the literature examines the impact of performance feedback on two evidence-based classroom management strategies: praise and opportunities to respond (OTRs).

Cavanaugh, B. (2013). Performance feedback and teachers' use of praise and opportunities to respond: A review of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children, 111-137.

Comparison of Two Community Alternatives to Incarceration for Chronic Juvenile Offenders.

The relative effectiveness of group care (GC) and multidimensional treatment foster care (MTFC) was compared in terms of their impact on criminal offending, incarceration rates, and program completion outcomes for 79 male adolescents who had histories of chronic and serious juvenile delinquency.

Chamberlain, P., & Reid, J. B. (1998). Comparison of two community alternatives to incarceration for chronic juvenile offenders. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 66(4), 624.

A systematic review of peer-mediated interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder

Peer mediated intervention (PMI) is a promising practice used to increase social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). PMIs engage typically developing peers as social models to improve social initiations, responses, and interactions.

Chang, Y. C., & Locke, J. (2016). A systematic review of peer-mediated interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in autism spectrum disorders, 27, 1-10.

An Assessment of the Evidence-Base for School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

This study sought to extend the work of Horner et al. (2010) in assessing the evidence base for SWPBS. However, unlike in the Horner et al. (2010) study, in this study the proposed criteria were applied to individual studies.

Chitiyo, M., May, M. E., & Chitiyo, G. (2012). An assessment of the evidence-base for school-wide positive behavior support. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(1), 1-24.

Effects of Classwide Positive Peer “Tootling” to Reduce the Disruptive Classroom Behaviors of Elementary Students with and without Disabilities

The purpose of this study was to examine the use of a classwide positive peer reporting intervention known as ‘‘tootling’’ in conjunction with a group contingency procedure to reduce the number of disruptive behaviors in a third-grade inclusive classroom.

Cihak, D. F., Kirk, E. R., & Boon, R. T. (2009). Effects of classwide positive peer “tootling” to reduce the disruptive classroom behaviors of elementary students with and without disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education, 18(4), 267.

Use of Self-Modeling Static-Picture Prompts via a Handheld Computer to Facilitate Self-Monitoring in the General Education Classroom

This study was designed to evaluate the effects of a combined self-monitoring and static self-model prompts procedure on the academic engagement of three students with autism served in general education classrooms

Cihak, D. F., Wright, R., & Ayres, K. M. (2010). Use of self-modeling static-picture prompts via a handheld computer to facilitate self-monitoring in the general education classroom. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 136-149.

Opportunities suspended: The devastating consequences of zero tolerance and school discipline policies. Report from a national summit on zero tolerance.

This is the first comprehensive national report to scrutinize the impact of strict Zero Tolerance approach in the America public school. This report illustrate that Zero Tolerance is unfair, is contrary to developmental needs of children, denies children educational opportunities, and often results in the criminalization of children.

Civil Rights Project. (2000). Opportunities suspended: The devastating consequences of zero tolerance and school discipline policies.

Assessing the Implementation of the Good Behavior Game: Comparing Estimates of Adherence, Quality, and Exposure

Treatment fidelity assessment is critical to evaluating the extent to which interventions, such as the Good Behavior Game, are implemented as intended and impact student outcomes. The assessment methods by which treatment fidelity data are collected vary, with direct observation being the most popular and widely recommended.

Collier-Meek, M. A., Fallon, L. M., & DeFouw, E. R. (2020). Assessing the implementation of the Good Behavior Game: Comparing estimates of adherence, quality, and exposure. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 45(2), 95-109.

Development and initial evaluation of the measure of active supervision and interaction.

Collier-Meek, M. A., Johnson, A. H., & Farrell, A. F. (2018). Development and initial evaluation of the measure of active supervision and interaction. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 43(4), 212-226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508417737516

Using active supervision and precorrection to improve transition behaviors in an elementary school.

Investigated the effect of a school-wide intervention plan, consisting of pre-correction and active supervision strategies, on the social behavior of elementary students in major transition settings.

Colvin, G., Sugai, G., Good, R. H., & Lee, Y. (1997). Using active supervision and precorrection to improve transition behaviors in an elementary school. School Psychology Quarterly, 12(4), 344–363. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088967

Positive greetings at the door: Evaluation of a low-cost, high-yield proactive classroom management strategy

The purpose of this study was to conduct an experimental investigation of the Positive Greetings at the Door (PGD) strategy to improve middle school students’ classroom behavior.

Cook, C. R., Fiat, A., Larson, M., Daikos, C., Slemrod, T., Holland, E. A., Thayer, A. J., & Renshaw, T. (2018). Positive greetings at the door: Evaluation of a low-cost, high-yield proactive classroom management strategy. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(3), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717753831

Using Parents as a Therapist to Evaluate Appropriate Behavior of Their Children: Application to a Tertiary Diagnostic Clinic

The authors conducted a preliminary analysis of maintaining variables for children with conduct disorders in an outpatient clinic. The assessment focused on appropriate child behavior and was conducted to formulate hypotheses regarding maintaining contingencies.

Cooper, L. J., Wacker, D. P., Sasso, G. M., Reimers, T. M., & Donn, L. K. (1990). Using parents as therapists to evaluate appropriate behavior of their children: Application to a tertiary diagnostic clinic. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23(3), 285-296.

Disproportionality reduction in exclusionary school discipline: A best-evidence synthesis

A full canon of empirical literature shows that students who are African American, Latinx, or American Indian/Alaskan Native, and students who are male, diagnosed with disabilities, or from low socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to experience exclusionary discipline practices in U.S. schools. Though there is a growing commitment to mitigating discipline disparities through alternative programming, it is clear that disproportionality in the application of harmful discipline practices persists.

Cruz, R. A., Firestone, A. R., & Rodl, J. E. (2021). Disproportionality reduction in exclusionary school discipline: A best-evidence synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 91(3), 397-431.

Peer Management Interventions: A Meta-Analytic Review of Single-Case Research

This meta-analysis of single-case research synthesized the results of 29 studies examining the effectiveness of school-based peer management interventions.

Dart, E. H., Collins, T. A., Klingbeil, D. A., & McKinley, L. E. (2014). Peer management interventions: A meta-analytic review of single-case research. School Psychology Review, 43(4), 367-384.

A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Interventions Aimed to Prevent or Reduce Violence in Teen Dating Relationships

The issue of sexual harassment has been front page news this past year. What does the research tell us about school interventions designed to reduce sexual harassment? This meta-analysis examines research on the topic and provides insight into how effective current efforts are at stemming incidents of this serious problem. This review provides a quantitative synthesis of empirical evaluations of school-based programs implemented in middle and high schools designed to prevent or reduce incidents of dating violence. This meta-analysis of 23 studies indicates school-based programs having no significant impact on dating violence perpetration and victimization; however, they can have a positive influence on dating violence knowledge and student attitudes.

De La Rue, L., Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2017). A meta-analysis of school-based interventions aimed to prevent or reduce violence in teen dating relationships. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 7-34.

A Meta-Analytic Review of Experiments Examining the Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation

A meta-analysis of 128 studies examined the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological bulletin, 125(6), 627.

Meta-analytic study on treatment effectiveness for problem behaviors with individuals who have mental retardation

The author's objective is to assess treatment effectiveness for problem behaviours of individuals who have mental retardation.

Didden, R., Duker, P. C., & Korzilius, H. (1997). Meta-analytic study on treatment effectiveness for problem behaviors with individuals who have mental retardation. AJMR-American Journal on Mental Retardation, 101(4), 387-399.

Self-Graphing of On-Task Behavior: Enhancing the Reactive Effects of Self-Monitoring on On-Task Behavior and Academic Performance

This study investigated the effects of self-graphing on improving the reactivity of self-monitoring procedures for two students with learning disabilities.

DiGangi, S. A., Maag, J. W., & Rutherford Jr, R. B. (1991). Self-graphing of on-task behavior: Enhancing the reactive effects of self-monitoring on on-task behavior and academic performance. Learning Disability Quarterly, 14(3), 221-230.

The Effects of Tootling via ClassDojo on Student Behavior in Elementary Classrooms.

The current study was designed to evaluate the effects of a tootling intervention, in which students report on peers' appropriate behavior, modified to incorporate ClassDojo technology, on class-wide disruptive behavior and academically engaged behavior.

Dillon, M. B. M., Radley, K. C., Tingstrom, D. H., Dart, E. H., Barry, C. T., & Codding, R. (2019). The Effects of Tootling via ClassDojo on Student Behavior in Elementary Classrooms. School Psychology Review, 48(1).

Positive Behavior Support and Applied Behavior Analysis A Familial Alliance

The purpose of this article is to address some of the key points of confusion, identify areas of overlap and distinction, and facilitate a constructive and collegial dialog between proponents of the PBS and ABA perspectives.

Dunlap, G., Carr, E. G., Horner, R. H., Zarcone, J. R., & Schwartz, I. (2008). Positive behavior support and applied behavior analysis: A familial alliance. Behavior Modification, 32(5), 682-698.

Choice making to promote adaptive behavior for students with emotional and behavioral challenges

Two analyses investigated the effects of choice making on the responding of elementary school students with emotional and behavioral challenges.

Dunlap, G., DePerczel, M., Clarke, S., Wilson, D., Wright, S., White, R., & Gomez, A. (1994). Choice making to promote adaptive behavior for students with emotional and behavioral challenges. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(3), 505-518.

Functional Communication Training to Reduce Challenging Behavior: Maintenance and Application in New Settings

The authors evaluated the initial effectiveness, maintenance, and transferability of the results of functional communication training as an intervention for the challenging behaviors exhibited by 3 students.

Durand, V. M., & Carr, E. G. (1991). Functional communication training to reduce challenging behavior: Maintenance and application in new settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24(2), 251-264.

The Good Behavior Game: A Best Practice Candidate as a Universal Behavioral Vaccine

Could there be a behavioral vaccine, nearly as simple as antiseptic handwashing, which might significantly reduce the mortality and morbidity of multiproblem behavior? Yes, there could be. This paper details what one might be and how it might become as common as a doctor or nurse washing hands with an antiseptic solution

Embry, D. D. (2002). The Good Behavior Game: A best practice candidate as a universal behavioral vaccine. Clinical child and family psychology review, 5(4), 273-297.

Outcomes for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders and their families : programs and evaluation best practices

Presents some of the current best practices in services for children and their families, as well as in the research and evaluation of these services.

Epstein, M. H., Kutash, K. E., & Duchnowski, A. E. (1998). Outcomes for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders and their families: Programs and evaluation best practices. Pro-Ed.

Reducing Behavior Problems in the Elementary School Classroom

This guide explores the challenges involved in providing the optimum climate for learning and provides recommendations for encouraging positive behavior and reducing negative behavior.

Epstein, M., Atkins, M., Cullinan, D., Kutash, K., & Weaver, K. (2008). Reducing behavior problems in the elementary school classroom. IES Practice Guide, 20(8), 12-22.

An evaluation of the effectiveness of teacher- vs. student-management classroom interventions.

The review contains a comprehensive evaluation of studies that have directly compared school‐based, teacher‐ vs. student‐management interventions.

Fantuzzo, J. W., Polite, K., Cook, D. M., & Quinn, G. (1988). An evaluation of the effectiveness of teacher‐vs. student‐management classroom interventions. Psychology in the Schools, 25(2), 154-163.

Effects of prompting appropriate behavior on the off-task behavior of two middle school students.

This study used a single-subject alternating treatment design, with a baseline phase, to explore the relationship between the presence (or absence) of prompting and off-task behavior of two male middle school students in general education.

Faul, A., Stepensky, K., & Simonsen, B. (2012). Effects of prompting appropriate behavior on the off-task behavior of two middle school students. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions, 14(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300711410702

Teaching behaviors, academic learning time, and student achievement: An overview.

The purpose of the Beginning Teacher Evaluation Study1 (BTES) was to identify teaching activities and classroom conditions that foster student learning in ele-mentary schools. The study focused on instruction in reading and mathematics at grades two and five.

Fisher, C. W., Berliner, D. C., Filby, N. N., Marliave, R., Cahen, L. S., & Dishaw, M. M. (1981). Teaching behaviors, academic learning time, and student achievement: An overview. The Journal of classroom interaction, 17(1), 2-15.

Effects of the Good Behavior Game on Challenging Behaviors in School Settings

The purposes of this review were to (a) describe and quantify the effect of the Good Behavior Game on various challenging behaviors in school and classroom settings and (b) understand characteristics of the intervention that may affect the magnitude of the outcomes

Flower, A., McKenna, J. W., Bunuan, R. L., Muething, C. S., & Vega Jr, R. (2014). Effects of the Good Behavior Game on challenging behaviors in school settings. Review of educational research, 84(4), 546-571.

The utilization and effects of positive behavior support strategies on an urban school playground.

The purpose of this study was to examine how the implementation of a recess intervention within the context of School-wide Positive Behavior Support (SwPBS), a systemwide, team-driven, data-based decision-making continuum of support, affected disruptive student behavior and teacher supervision on the playground in an urban elementary school

Franzen, K., & Kamps, D. (2008). The utilization and effects of positive behavior support strategies on an urban school playground. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10(3), 150-161.

Making life easier with effort: Basic findings and applied research on response effort

This paper summarize basic research on response effort and explore the role of effort in diverse applied areas including deceleration of aberrant behavior, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oral habits, health care appointment keeping, littering, indexes of functional disability, and problem-solving.

Friman, P. C., & Poling, A. (1995). Making life easier with effort: Basic findings and applied research on response effort. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28(4), 583-590.

Back to basics: Rules, praise, ignoring, and reprimands revisited

Research begun in the 1960s provided the impetus for teacher educators to urge classroom teachers to establish classroom rules, deliver high rates of verbal/nonverbal praise, and, whenever possible, to ignore minor student provocations. The research also discuss several newer strategies that warrant attention.

Gable, R. A., Hester, P. H., Rock, M. L., & Hughes, K. G. (2009). Back to basics: Rules, praise, ignoring, and reprimands revisited. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(4), 195-205.

A Review of Schoolwide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports as a Framework for Reducing Disciplinary Exclusions

The purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic meta-analysis of RCTs on SWPBIS. Ninety schools, including both elementary and high schools, met criteria to be included in this study. A statistically significant large treatment effect (g = −.86) was found for reducing school suspension. No treatment effect was found for office discipline referrals.

Gage, N.A., Whitford, D.K. and Katsiyannis, A., 2018. A review of schoolwide positive behavior interventions and supports as a framework for reducing disciplinary exclusions. The Journal of Special Education, p.0022466918767847.

Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy

Despite a significant drop in the use of corporal punishment in schools, a recent study finds corporal punishment is currently legal in 19 states and over 160,000 children are subject to corporal punishment in schools each year. This policy report examines the prevalence and geographic dispersion of corporal punishment in U.S. public schools. The research finds corporal punishment is disproportionately applied to children who are Black, to boys and children with disabilities. Black students experienced corporal punishment at twice the rate of white students, 10 percent versus 5 percent. This report summarizes sources of concern about school corporal punishment, reviewing state policies related to school corporal punishment, and discusses the future of school corporal punishment in state and federal policy.

Gershoff, E. T., & Font, S. A. (2016). Corporal Punishment in US Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy. Social Policy Report, 30(1).

When and why incentives (don't) work to modify behavior.

This book discuss how extrinsic incentives may come into conflict with other motivations and examine the research literature in which monetary incentives have been used in a nonemployment context to foster the desired behavior. The conclusion sums up some lessons on when extrinsic incentives are more or less likely to alter such behaviors in the desired directions.

Gneezy, U., Meier, S., & Rey-Biel, P. (2011). When and why incentives (don't) work to modify behavior. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(4), 191-210.

Interdependent, dependent, and independent group contingencies for controlling disruptive behavior

Three group-oriented contingency systems (interdependent, dependent, and independent) were compared in a modified reversal design to evaluate each system's effectiveness in controlling the disruptive behavior of a self-contained classroom of educable mentally retarded children.

Gresham, F. M., & Gresham, G. N. (1982). Interdependent, dependent, and independent group contingencies for controlling disruptive behavior. The Journal of Special Education, 16(1), 101-110.

Supporting Appropriate Student Behavior Overview.

This overview focuses on proactive strategies to support appropriate behavior in school settings.

Guinness, K., Detrich, R., Keyworth, R. & States, J. (2019). Overview of Supporting Appropriate Behavior. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/classroom-appropriate-behaviors.

Supporting Appropriate Behaviors

This overview focuses on proactive strategies to support appropriate behavior in school settings.

Guinness, K., Detrich, R., Keyworth, R. & States, J. (2019). Overview of Supporting Appropriate Behavior. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/classroom-appropriate-behaviors.

Decreasing Inappropriate Behavior Overview.

This overview describes strategies for how school personnel can respond when disruptive behavior occurs, including (1) negative consequences that can be applied as primary interventions, (2) functional behavior assessment, and (3) function-based, individualized interventions characteristic of the secondary or tertiary tiers of a multitiered system of support.

Guinness, K., Detrich, R., Keyworth, R. & States, J. (2020). Overview of Decreasing Inppropriate Behavior. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/classroom-inappropriate-behaviors.

Rules and Procedures Overview

This overview summarizes research about the effects of rules on appropriate and inappropriate behavior in school settings and provides recommendations for incorporating rules effectively into a behavior management program.

Guinness, K., Detrich, R., Keyworth, R. & States, J. (2020). Overview of Rules and Procedures. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/classroom-rules-procedures.

Structured Environment Overview

This overview summarizes research on the effects of the physical classroom environment on student behavior.

Active Supervision Overview

This overview describes the definitions and importance of active supervision. This overview also provides research and implementations of this strategy.

Guinness, K., Detrich, R., Keyworth, R. & States, J. (2020). Overview of Supporting Appropriate Behavior. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/classroom-active-supervision

Effectiveness of Functional Communication Training With and Without Extinction and Punishment: A Summary of 21 Inpatient Cases

The main purposes of the present study were to evaluate the efficacy of FCT for treating severe problem behavior in a relatively large sample of individuals with mental retardation (N = 21) and to determine the contribution of extinction and punishment components to FCT treatment packages.

Hagopian, L. P., Fisher, W. W., Sullivan, M. T., Acquisto, J., & LeBlanc, L. A. (1998). Effectiveness of functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment: A summary of 21 inpatient cases. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 31(2), 211-235.

Modification of Behavioral Problems in the Home with a Parent as Observer and Experimenter

Four parents enrolled in a Responsive Teaching class carried out experiments using procedures they had devised for alleviating their children's problem behaviors. The techniques used involved different types of reinforcement, extinction, and punishment.

Hall, R. V., Axelrod, S., Tyler, L., Grief, E., Jones, F. C., & Robertson, R. (1972). MODIFICATION OF BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS IN THE HOME WITH A PARENT AS OBSERVER AND EXPERIMENTER 1. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5(1), 53-64.

Reinforcement schedule thinning following treatment with functional communication training

The authors evaluated four methods for increasing the practicality of functional communication training (FCT) by decreasing the frequency of reinforcement for alternative behavior.

Hanley, G. P., Iwata, B. A., & Thompson, R. H. (2001). Reinforcement schedule thinning following treatment with functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(1), 17-38.

Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood

To examine the long-term effects of an intervention combining teacher training, parent education, and social competence training for children during the elementary grades on adolescent health-risk behaviors at age 18 years.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., Kosterman, R., Abbott, R., & Hill, K. G. (1999). Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 153(3), 226-234.

Active supervision, precorrection, and explicit timing: A high school case study on classroom behavior.

This study is a replication of a study that investigated the combination of active supervision, precorrection, and explicit timing. The purpose of the study was to decrease student problem behavior, reduce transition time, and support maintenance of the intervention in the setting.

Haydon, T. & Kroeger, S. D. (2016). Active supervision, precorrection, and explicit timing: A high school case study on classroom behavior. Preventing School Failure, 60(1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2014.977213

Effective Use of Behavior-Specific Praise: A Middle School Case Study.