School Leadership Models

Leadership Models PDF

Donley, J., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, (2020). Leadership Models. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/quality-leadership-leadership-models

Principals exert a strong influence on student learning and achievement through their ability to impact the types of organizational school features necessary for high-quality teaching and learning (Hitt & Tucker, 2016; Leithwood, Harris, & Hopkins, 2020; Leithwood, Harris, & Strauss, 2010; Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008; Supovitz, Sirinides, & May, 2010). While leadership effects on student learning are mediated by other conditions that more directly impact achievement (Hallinger & Heck, 2010; Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom, & Anderson, 2010), principals do exert influence over factors such as school climate and teacher working conditions, and make human capital (i.e., teacher hiring) and professional development decisions that indirectly influence student learning outcomes (Cannata et al., 2017; Sebastian & Allensworth, 2012).

Researchers in educational leadership have proposed theoretical models of school leadership that identify and organize the types of competencies and characteristics desired in school leaders. This review highlights major models that have been influential in the field and discusses evidence for their efficacy in explaining school leaders’ influence.

Historical Overview and Background

Effective principals are effective leaders. While no single definition has been identified in the research literature (Bush, 2008), school leadership has generally been referred to as “the work of mobilizing and influencing others to articulate and achieve the school’s shared intentions and goals” (Leithwood & Riehl, 2005, p. 14). The scholarship on leadership prior to 1950 focused on the personality traits that distinguished leaders from followers, arguing that traits such as charisma and diligence were essential and often found in “great men” serving as leaders (Gümüş, Bellibaş, Esen, & Gümüş, 2018; Krüger & Scheerens, 2012). Attention then shifted to the behaviors that were thought to be indicative of effective school leaders (Krüger & Scheerens, 2012). Other prominent models during this time period included one positing the importance of contingency/situational leadership, which argued that effective leadership was highly dependent on leaders’ school context (Gümüş et al., 2018).

The “effective schools” research of the 1980s followed, providing qualitative evidence for schools that were able to help all students thrive no matter their socioeconomic background (Clark, Lotto, & Astuto, 1984). This body of research determined that strong leaders led these effective schools (Purkey & Smith, 1983) and served as the cornerstone of the development of school leadership models that are well studied today, such as instructional leadership (Gümüş et al., 2018; Hallinger, Gümüş, & Bellibaş, 2020). The transition into the 21st century brought an increased emphasis on accountability in the United States and globally, with the metric of student achievement seen as the basis for assessing educational effectiveness and, in turn, the effectiveness of principals (Hallinger et al., 2020).

Effective school leaders today are thought to have” a set of competencies manifested by behavior that relates to effective or outstanding performance in a specific job or role” (Hitt, Meyers, Woodruff, & Zhu, 2019, p. 190). Principals’ practices represent their competencies in various leadership areas, and research has attempted to investigate the relationship between these behaviors/practices and student, teacher, and school outcomes. Leadership models have helped researchers clarify the definition and practices of effective leadership and how principals influence schools from varying perspectives.

While school leadership has been the object of a great deal of discussion and research in the past few decades, most systematic research reviews have incorporated all types of educational leadership studies without isolating and studying leadership models per se (Gümüş et al., 2018). This overview examines contemporary prevalent school leadership models along with supporting research for their efficacy in explaining principals’ effectiveness.

Instructional Leadership

Defined as “school leadership intended to influence school and classroom teaching and learning processes with the goal of improving learning for all students” (Hallinger et al., 2020, p. 1632), instructional leadership emerged from studies on the characteristics of effective principals to become one of the most intensely studied leadership models (Gümüş et al., 2018; Tian & Huber, 2019). Instructional leadership dominated the field from 1980 to 1995 (Gümüş et al., 2018; Hallinger et al., 2020). After that, scholars focused on other leadership models, for example, distributed or shared leadership, because of policy shifts such as teacher professionalization (Hallinger et al., 2020). However, interest in instructional leadership grew again after 2010 (Gümüş et al., 2018).

The first conceptual model to address instructional leadership grew out of a research synthesis on the topic, proposing how principals’ instructional leadership impacted student learning outcomes, and how this impact depended on variables such as instructional climate and community context (Bossert, Dwyer, Rowan, & Lee, 1982). Hallinger’s Principal Instructional Management Rating Scale (PIMRS) concurrently provided a key research tool and framework that produced abundant lines of research addressing instructional leadership (Hallinger & Heck, 1996, 1998; Hallinger & Murphy, 1985). This framework suggested that instructional leaders must balance three key functions: (1) developing the school’s mission by framing and communicating school goals; (2) managing the instructional program by coordinating curriculum, assessing instructional effectiveness, and monitoring learning; and (3) instilling a positive school climate by maintaining high visibility, enforcing academic standards, and providing professional development coupled with protected teacher instructional time (Hallinger, 2005; Hallinger & Murphy, 1985).

A variety of quantitative research reviews have affirmed positive, though mediated, relationships between principal’s instructional leadership and student learning and other school outcomes (Bossert et al., 1982; Hallinger & Heck, 1996; Leithwood et al., 2020; Liebowiz & Porter, 2019; Louis et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2008; Scheerens, 2012; Witziers, Bosker, & Krüger, 2003). A recent meta-analysis of the empirical literature, for example, documented a strong relationship between principals’ focus on instruction-specific support (including behaviors related to planning and providing professional development) and teaching effectiveness, student achievement, and school organizational health (Liebowitz & Porter, 2019). In their review of qualitative and quantitative research published from 2001 to 2012, Osborne-Lampkin, Folsom, and Herrington (2015) identified instructional management behaviors that addressed classroom instruction and curricula as one of four principal competencies that significantly influenced student achievement.

Recent content analyses of instructional leadership research suggest that these studies have largely shifted toward exploring models that consider how the influence of instructional leadership is moderated by other factors, and the relationship between leadership and student learning and other school and teacher variables (Boyce & Bowers, 2018; Hallinger, 201l). In a review of 109 studies published between 1988 and 2013 that used Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS) data, Boyce and Bowers (2018) noted themes found in the instructional leadership research and confirmed a trend in the field from a narrow focus on instructional leadership toward broader notions of “leadership for learning” (Leithwood, Harris, & Hopkins, 2008; Murphy, Elliott, Goldring, & Porter, 2007)

This broader concept of instructional leaders is reflected in the research on the behaviors of effective principals. Effective school leaders engage in side-by-side professional learning with their faculty as they learn about curricular and instructional improvements (Robinson et al., 2008); this action strengthens principals’ knowledge and capacity to be a resource and support to teachers, and enhances their credibility and legitimacy as instructional leaders in schools (Murphy et al., 2006). Instructional leadership also involves a principal’s active involvement in planning, coordinating, and assessing curriculum and teaching through activities such as discussions about and influence over vertical/horizontal curriculum alignment, and observation of and feedback on classroom teaching (Murphy et al., 2006; Robinson et al., 2008).

School leaders exerting instructional leadership protect instructional time during the school day, limit disruptions, and encourage teacher and student attendance (Hitt & Tucker, 2016). They view assessment as pivotal to evaluating student progress and making adjustments based on regularly collected formative and summative data; they also ensure that this data is disaggregated by indicators important for tracking progress toward school improvement goals, such as by ethnicity, special education status, and socioeconomic status (Murphy et al., 2006). Instructional leaders ensure that students’ backgrounds are incorporated into the instructional program and create personalized and culturally responsive learning environments (Hitt & Tucker, 2008; Leithwood, 2012; Murphy et al., 2006; Sebring, Allensworth, Bryk, Easton, & Luppescu, 2006).

Murphy and Hallinger (1988) were among researchers who took a broader view of instructional leadership to argue for the inclusion of a principal’s skill in organizational management, which includes managing budgets, providing a safe learning environment, acquiring and allocating resources strategically, and building collaborative decision-making processes. The importance of organizational management has been validated in research conducted more recently, and has been shown to have a strong influence on student achievement (Grissom & Loeb, 2011; Horng, Klasik, & Loeb, 2010; Liebowitz & Porter, 2019). Strong organizational management skills allow principals to align support systems so that teachers can maximize instructional best practices and enhance student achievement (Grissom & Loeb, 2011; Horng et al., 2010). In fact, instructional leadership and organizational management are both likely components of the broader construct of leadership effectiveness (Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010; Sebastian, Allensworth, Wiedermann, Hochbein, & Cunningham, 2019).

Distributed or Shared Leadership

As the notion of the need for a strict bureaucratic hierarchy in schools eroded because of the democratic and participative school restructuring movement that called for empowering teachers as professional educators (Marks & Louis, 1997), the concept of instructional leadership as a principal-centered practice evolved into shared instructional leadership, in which the principal and teachers work together to determine the best instructional practices for the school (Marks & Printy, 2003). Also referred to as distributed (Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001, 2004) or collective leadership (Browne-Ferrigno, 2016), this model points out that principals generally are unable to enact instructional leadership alone (Hallinger, 2005) and, in fact, inflexible hierarchies can produce low staff morale and performance (Tian, Risku, & Collin, 2016). Principals need teachers to fulfill leadership roles and perform leadership tasks; teachers are the elements of instructional leadership that form a collaborative school culture (Spillane et al., 2001, 2004).

Distributed leadership is effective when informal responsibilities are shared among educators based on patterns of expertise, such as teams created to solve problems of practice (DeFlaminis, 2013; Hulpia & Devos, 2010). The notion of distributed leadership was operationalized in the Annenberg Foundation’s Distributed Leadership Project (DLP), which sought to build leadership capacity in urban schools with highly diverse student populations and in need of substantial school improvement (DeFlaminis, 2013). The DLP provided principal preparation to establish a distributed leadership mindset, and assisted with the development of distributed leadership teams to build leadership capacity in Philadelphia schools. Positive results in the form of multiple leadership team outcomes (e.g., effective team functioning and trust and efficacy levels among team members) led to the program being replicated in New York in 2015 (Harris & DeFlaminis, 2016).

Distributed leadership has also received an extensive amount of research attention, particularly in the past decade (Gümüş et al., 2018), and the body of research has generally confirmed the leadership potential of teachers (Tian & Huber, 2019). This leadership style has been associated with positive outcomes such as improved student performance in math and reading, teacher satisfaction, enhanced teacher skills, and individual and collective teacher efficacy (Hallinger & Heck, 2010; Heck & Hallinger, 2009; Leithwood & Mascall, 2008; Mascall, Leithwood, Strauss, & Sacks, 2008; Supovitz & Riggan, 2012), as well as teacher retention (Booker & Glazerman, 2009; Cowan & Goldhaber, 2016).

The effectiveness of distributed leadership on school outcomes and student achievement continues to be documented in the recent literature (Leithwood et al., 2020). However, how leadership is distributed produces diverse outcomes and results, and its effectiveness depends on the way in which leadership roles and responsibilities are distributed to optimally address the organization’s needs through staff expertise, which varies from school to school (Eckert, 2019; Heck & Hallinger, 2009; Leithwood & Mascall, 2008; Leithwood et al., 2020). As Harris and DeFlaminis (2016) noted, “distributed leadership is not a panacea, it depends on how it is shared, received and enacted” (p. 143).

Transformational Leadership

As instructional and distributed leadership models grew in prominence, another important line of research addressed the leadership required to turn around poorly performing schools. These researchers suggested that transformational leadership in which principals and other school leaders serve as change agents who inspire and motivate staff to improve organizational performance collaboratively, was required for this Herculean task (Hallinger, 1992; Leithwood, 1994). Transformational leadership stresses the following factors: “building school vision and goals, providing intellectual stimulation, offering individualized support, modeling professional practices and values, demonstrating high performance expectations, and developing structures to foster participation in school decisions” (Urick & Bowers, 2014, p. 100). Transformative school leadership connects leaders to teachers within continual improvement processes so that combined efforts result in a collective efficacy and a positive school trajectory, with teachers motivated to look past their individual interests and invest in the success of the school as a whole (Leithwood, 2012).

A series of meta-analyses showed a modest correlation between transformational leadership and student achievement. However, they showed stronger relationships to teacher and school process outcomes (Leithwood & Sun, 2012; Sun & Leithwood, 2012, 2015); individual direction-setting leadership practices such as “developing a shared vision” and “holding high performance expectations” were strongly related to these outcomes. Robinson et al.’s (2008) meta-analysis of research addressing the impact of leadership styles showed that instructional leadership had 3 to 4 times the effects on student achievement as transformative leadership, although others subsequently argued that the distinctions drawn in the study between instructional and transformational leadership may have been overly rigid (Day, Gu, & Sammons, 2016).

In fact, a study of highly improved schools in England revealed that principals exerted both instructional and transformational leadership strategies to build teachers’ commitment to, and capacity for, improvement by introducing, implementing, and sustaining standards of high-quality teaching and learning (Day et al., 2011). This integrated model was echoed in research by Marks and Printy (2003), who noted that integrated leadership, which stresses the importance of both instructional and transformational principal competencies, was found in schools with higher teaching quality and achievement. Integrated leadership “acknowledges that a solid, results-focused management approach must be in place before, or at least simultaneously to, expecting teachers to engage in transcendental and transformative work” (Hitt & Tucker, 2016, p. 535).

Integrated Leadership

Several lines of research have attempted to unify the results from research on instructional, transformational, and distributed leadership into an integrated model of school leadership while further considering how school context influences principals’ enactment of leadership behaviors. Marks and Printy (2003) found that transformational leadership was a necessary, but not sufficient, component of shared instructional leadership. The investigators suggested that this form of integrated leadership created a synergy among principals and teachers around instructional innovation and improvement. Researchers have extended the work of Marks and Printy, finding that principals’ leadership styles vary depending on their background and school context and needs, and that principals may simultaneously practice different leadership behaviors accordingly to address these factors (Boberg & Bourgeois, 2016; Bruggencate, Luyten, Scheerens, & Sleegers, 2012; Day et al., 2016; Urick & Bowers, 2014). For example, Hallinger (2018) identified several types of contexts that shape leadership practice, including cultural, economic, community, political, and school improvement contexts. Flexibility to consider the school’s context or situation allows leaders to not only understand an issue but also adapt solutions accordingly to optimize outcomes (Daly, 2009; Leithwood, 2012; Marks & Printy, 2003; Murphy et al., 2006; Sebring et al., 2006).

In an analysis of instructional leadership research, Boyce and Bowers (2018) developed an integrated leadership model that attempted to depict the relationship among key factors that emerged from research findings. They noted four instructional leadership themes (principal leadership and influence, teacher autonomy and influence, adult development, and school climate), and described their relationship with three other factors emerging from the literature (teacher satisfaction, commitment, and retention), developing an integrated model that included both shared instructional leadership and human resource management. They found, for example, that teacher autonomy and perceptions of influence combine to form a reciprocal relationship with principal leadership, together forming the foundation for instructional leadership.

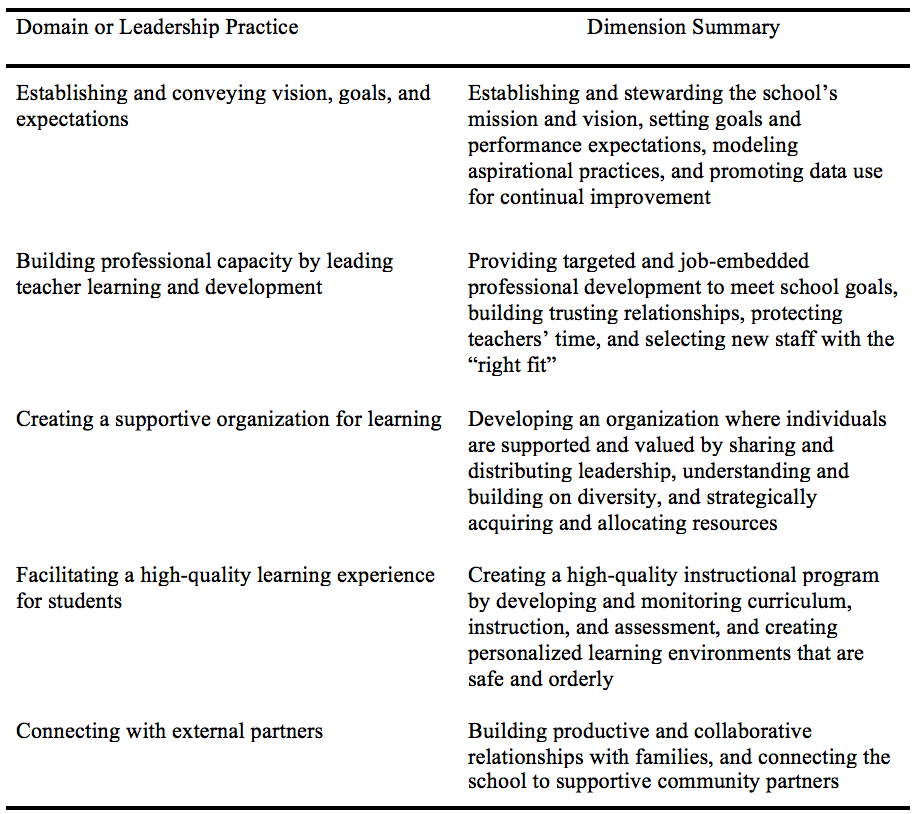

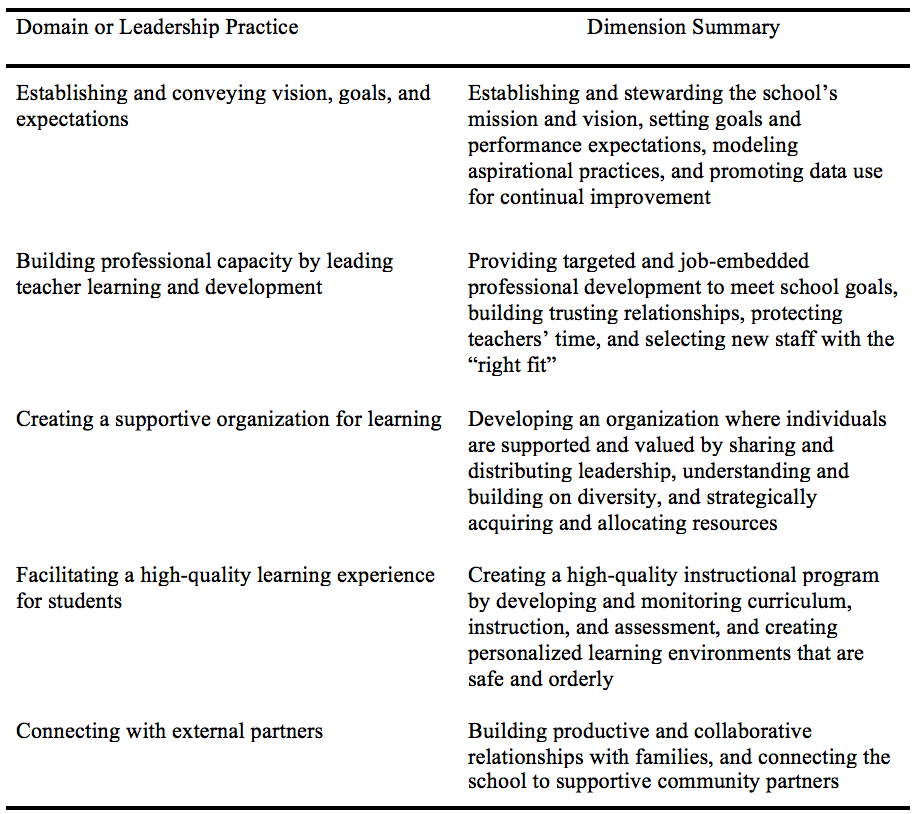

Hitt and Tucker (2016) reviewed 56 studies and three major leadership frameworks in an attempt to synthesize the major findings and frameworks in the field into a unified model of effective leader practices (see Table 1). The three frameworks reviewed were the Ontario Leadership Framework, or OLF (Leithwood, 2012); Learning-Centered Leadership Framework (Murphy et al., 2006); and Essential Supports Framework (Sebring et al., 2006). While a discussion of each of these frameworks is beyond the scope of this paper, Hitt and Tucker’s Unified Framework provides an example of how elements of instructional, distributed or shared, and transformational leadership are integrated into a contemporary leadership framework.

Table 1

Adapted from Hitt and Tucker (2016)

Leadership for Equity

While the cited leadership frameworks and accompanying leadership behaviors have been shown to positively influence school-level achievement measures, schools and school leaders are increasingly held responsible for other outcomes, most prominently equity (Leithwood et al., 2020). Equity has been referred to as “attention to the fairness of outcomes within the context of an unequal playing field” (Ishimaru & Galloway, 2014, p. 94). Leadership for equity has become an emergent focus of research over the past decade, as scholars have attempted to build upon and extend what is known about effective school leadership to include how leaders enact behavior that promotes equitable outcomes for all students (Oplatka, 2014; Tian & Huber, 2019).

Researchers have noted that principals who positively influence student achievement also incorporate students’ backgrounds into the instructional program and create personalized and culturally responsive learning environments (Hitt & Tucker, 2016; Leithwood, 2012; Murphy et al., 2006; Sebring et al., 2006); however, little attention and guidance have been given to how school leaders can most effectively address the frequent disparate academic outcomes observed for marginalized student groups and students of color resulting from persistent and pervasive opportunity gaps in educational systems (Darling-Hammond, 2010; Theoharis, 2007). The topics of culturally responsive school leadership (Khalifa, Gooden, & Davis, 2016) and leadership for social justice (Brayboy, Castagno, & Maughan, 2007; Ryan, 2006; Theoharis, 2007) have emerged as prevalent lines of inquiry addressed by school leadership researchers. For example, Khalifa et al. (2016) reviewed the literature on culturally responsive school leadership, concluding that culturally responsive leaders (1) develop critical awareness of their own values, beliefs and dispositions; (2) ensure that teacher use culturally responsive curricula and instruction; (3) create culturally responsive and welcoming school environments; and (4) engage student and families in community contexts by accepting and embracing students’ home cultures.

Leadership frameworks for educational equity are emerging as efforts to integrate the accumulating body of school leadership research with research addressing leadership for equity. For example, Ishimaru and Galloway (2014), in collaboration with researchers, practitioners, and community leaders with expertise in educational equity, developed a research-based organizational leadership conceptual framework for educational equity; it argues for a central emphasis on leadership practices that foster or inhibit equitable educational systems. This framework proposes 10 high-leverage equitable school leadership practices adapted from and aligned to national standards developed by the Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium (ISLLC):

- Construct and enact an equity vision that explicitly recognizes existing systemic inequities, and demonstrate high expectations for educator practice and student outcomes.

- Supervise for improvement of equitable teaching and learning, to include instructional practices such as culturally responsive teaching and differentiated instruction.

- Develop organizational leadership for equity in others, such as parents, students, and community members, by building their capacity for self-reflection regarding biases and assumptions, and collaborating to move instructional practices to become more equitable.

- Foster an equitable school culture by intentionally deepening the voices of students, families, and staff who have been traditionally marginalized and building relationships across the school community.

- Allocate resources (financial, material, time, human resources) to address the needs of students who traditionally have not been well served because of their ethnicity, language, or economic class.

- Hire, place, and retain personnel of color who also possess strong equity commitments, understanding, and skills.

- Collaborate with families and communities by establishing and maintaining meaningful and sustained relationships, engaging these stakeholders in school improvement for equity, and ensuring plenty of two-way communication.

- Engage in self-reflection and growth by examining one’s own identity, values, biases, and privileges, and developing and understanding how they operate in school and society both historically and currently.

- Model integrity, advocacy, conviction, and tenacity in pursuing equity.

- Influence the sociopolitical context by collaborating with stakeholders to address the roots of systemic inequities and publicly working toward socially just policy and implementation.

These leadership practices are “designed to support the professional growth and practice of leadership teams in creating more equitable education environments” (Ishimaru & Galloway, 2014, p. 120), rather than being entirely focused on the school principal. The framework also has implications for designing principal preparation programs, selecting and developing faculty for these preparation programs, implementing assessment licensure programs, evaluating principal effectiveness, and providing K–12 professional development programs (Galloway & Ishimaru, 2015).

Summary and Conclusions

School leadership has been the subject of extensive research, and several models have been framed to synthesize and organize what is known about how principals and other school leaders influence student, teacher, and school outcomes.

The instructional leadership model, in which principals are thought to exert a highly influential, though mediated, effect on teaching and learning, has received strong support in the research literature. Strong instructional leaders actively plan and participate in professional learning with teachers, involve themselves substantively in curriculum and teaching, and use data to monitor progress toward goals. Research shows that instructional leadership also broadly includes organizational management duties, such as resource acquisition and allocation, and providing safe learning environments.

The distributed or shared leadership model emerged as research accumulated regarding the benefits of teacher leadership and the need to spread the responsibility for school improvement beyond the building principal. Shared leadership has received extensive research support, suggesting that these collaborative leadership cultures are associated with positive teacher and student outcomes; however, leadership roles and responsibilities must be tailored to the needs of the school’s context by appropriately using staff’s areas of expertise.

The transformational leadership model, in which principals or other school leaders act as change agents to inspire and motivate staff to work toward school, rather than individual, success, has become another prominent line of inquiry. Research has consistently documented relationships between key direction-setting leadership practices and teacher and school outcomes; however, it is likely that solid instructional and organizational leadership must form the basis for principals to be able to successfully exert transformative leadership strategies.

The integrated leadership model represents recent efforts to synthesize, organize, and unify the research on effective school leadership that has been addressed in instructional, distributed or shared, and transformational leadership models, as well as incorporate the school context in which leadership takes place. For example, the integrated model has suggested that instructional leadership likely is a result of the degree of teacher autonomy and influence and a principal’s human resource management strategies. Principals likely use elements of all three types of leadership styles or strategies, and recent leadership frameworks clearly reflect this integrated approach. Use of a broad array of leadership strategies is often crucial, particularly for principals leading schools in high-poverty communities.

Increasing attention in the field has been devoted to studying the leadership needed for advancing toward equitable outcomes for all students. Research on culturally responsive school leadership has described, for example, how leaders build bridges with families by embracing students’ home cultures, and develop teachers’ capacity to use culturally responsive instruction. Culturally responsive school leadership is reflected in a recent leadership framework that integrates national school leadership standards with this research, and proposes high-leverage school practices to support leadership teams as they seek to create more equitable school environments.

Citations

Boberg, J. E., & Bourgeois, S. J. (2016). The effects of integrated transformational leadership on achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 54(3), 357–374.

Booker, K., & Glazerman, S. (2009). Effects of the Missouri Career Ladder program on teacher mobility. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507470.pdf

Bossert, S. T., Dwyer, D. C., Rowan, B., & Lee, G. V. (1982). The instructional management role of the principal. Educational Administration Quarterly, 18(3), 34–64.

Boyce, J., & Bowers, A. J. (2018). Toward an evolving conceptualization of instructional leadership as leadership for learning: Meta-narrative review of 109 quantitative studies across 25 years. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(2), 161–182.

Brayboy, B. M. J., Castagno, A. E, & Maughan, E. (2007). Equality and justice for all? Examining race in education research. Review of Research in Education, 31(1), 159–194.

Browne-Ferrigno, T. (2016). Developing and empowering leaders for collective school leadership: Introduction to special issue. Journal of Research in Leadership Education, 11(2), 151-157.

Bruggencate, G. T., Luyten, H., Scheerens, J., & Sleegers, P. (2012). Modeling the influence of school leaders on student achievement: How can school leaders make a difference? Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(4), 699–732. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258132484_Modeling_the_Influence_of_School_Leaders_on_Student_Achievement_How_Can_School_Leaders_Make_a_Difference

Bryk A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bush, T. (2008). Leadership and management development in education. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

Cannata, M., Rubin, M., Goldring, E., Grissom, J. A., Neumerski, C. M., Drake, T. A., & Schuermann, P. (2017). Using teacher effectiveness data for information-rich hiring. Educational Administration Quarterly, 53(2), 180–222.

Clark, D. L., Lotto, L. S., & Astuto, T. A. (1984). Effective schools and school improvement: A comparative analysis of two lines of inquiry. Educational Administration Quarterly, 20(3), 41–68.

Cowan, J., & Goldhaber, D. (2016). National board certification and teacher effectiveness: Evidence from Washington State. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 9(3), 233–258.

Daly, A. J. (2009). Rigid response in an age of accountability: The potential of leadership and trust. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45(2), 168–216.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). The flat world and education: How America’s commitment to equity will determine our future. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Day, C., Gu, Q., & Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(2), 221–258.

Day, C., Sammons, P., Leithwood, K., Harris, A., Hopkins, D., Gu, Q., … Ahtaridou, E. (2011). Successful school leadership: Linking with learning and achievement. London, UK: Open University Press.

DeFlaminis, J. A. (2013). The implementation and replication of the distributed leadership program: More lessons learned and beliefs confirmed. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA.

Eckert, J. (2019). Collective leadership development: Emerging themes from urban, suburban, and rural high schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 55(3), 477–509.

Galloway, M. K., & Ishimaru, A. M. (2015). Radical recentering: Equity in educational leadership standards. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(3), 372–408.

Grissom, J. A., & Loeb, S. (2011). Triangulating principal effectiveness: How perspectives of parents, teachers, and assistant principals identify the central importance of managerial skills. American Educational Research Journal, 48(5), 1091–1123.

Gümüş, S., Bellibaş, M. S., Esen, M., & Gümüş, E. (2018). A systematic review of studies of leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 46(1), 25–48.

Hallinger, P. (1992). The evolving role of American principals: From managerial to instructional to transformational leaders. Journal of Educational Administration, 30(3), 35–48.

Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3), 221–239. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228633330_Instructional_Leadership_and_the_School_Principal_A_Passing_Fancy_that_Refuses_to_Fade_Away

Hallinger, P. (2011). A review of three decades of doctoral studies using the Principal Instructional Management Rating Scale: A lens on methodological progress in educational leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(2), 271–306.

Hallinger, P. (2018). Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 46(1), 5–24.

Hallinger, P., Gümüş, S. & Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2020). Are principals instructional leaders yet? A science map of the knowledge base on instructional leadership, 1940–2018. Scientometrics 122(3), 1629–1650. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338923620_%27Are_principals_instructional_leaders_yet%27_A_science_map_of_the_knowledge_base_on_instructional_leadership_1940-2018

Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1996). Reassessing the principal’s role in school effectiveness: A review of empirical research, 1980–1995. Educational Administration Quarterly, 32(1), 5–44.

Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1998). Exploring the principal’s contribution to school effectiveness: 1980–1995. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 9(2), 157–191.

Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2010). Leadership for learning: Does collaborative leadership make a difference in school improvement? Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 38(6), 654–678.

Hallinger, P., & Murphy, J. F. (1985). Assessing the instructional management behavior of principals. Elementary School Journal, 86(2), 217–247.

Harris, A., & DeFlaminis, J. (2016). Distributed leadership in practice: Evidence, misconceptions and possibilities. Management in Education, 30(4), 141–146.

Heck, R. H., & Hallinger, P. (2009). Assessing the contribution of distributed leadership to school improvement and growth in math achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 46(3), 659–689.

Hitt, D. H., Meyers, C. V., Woodruff, D., & Zhu, G. (2019). Investigating the relationship between turnaround principal competencies and student achievement. NASSP Bulletin, 103(3), 189–208.

Hitt, D. H., & Tucker, P. D. (2016). Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement: A unified framework. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 531–569.

Horng, E. L., Klasik, D., & Loeb, S. (2010). Principal’s time use and school effectiveness. American Journal of Education, 116(4), 491–523. https://cepa.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/Principal%27s%20Time%20Use%20AJE.pdf

Hulpia, H., & Devos, G. (2010). How distributed leadership can make a difference in teachers’ organizational commitment? A qualitative study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 565–575.

Ishimaru, A. M., & Galloway, M. K. (2014). Beyond individual effectiveness: Conceptualizing organizational leadership for equity. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 13(1), 93–146. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262057301_Beyond_Individual_Effectiveness_Conceptualizing_Organizational_Leadership_for_Equity

Khalifa, M. A., Gooden, M. A., & Davis, J. E. (2016). Culturally responsive school leadership: A synthesis of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1272–1311.

Krüger, M., & Scheerens, J. (2012). Conceptual Perspectives on School Leadership. In J. Scheerens (Ed.), School leadership effects revisited: Review and meta-analysis of empirical studies (pp. 1–30). New York, NY: Springer.

Leithwood, K. (1994). Leadership for school restructuring. Educational Administration Quarterly, 30(4), 498–518.

Leithwood, K. (2012). Ontario Leadership Framework 2012 with a discussion of the research foundations. Ottawa, Canada: Institute for Education Leadership. https://www.education-leadership-ontario.ca/application/files/2514/9452/5287/The_Ontario_Leadership_Framework_2012_-_with_a_Discussion_of_the_Research_Foundations.pdf

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership and Management, 28(1), 27–42. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alma_Harris/publication/251888122_Seven_Strong_Claims_about_Successful_School_Leadership/links/0deec5388768e8736d000000/Seven-Strong-Claims-about-Successful-School-Leadership.pdf

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership and Management, 40(1), 5–22.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading school turnaround: How successful school leaders transform low performing schools. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Leithwood, K., & Mascall, B. (2008). Collective leadership effects on student achievement. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 529–561. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b3d8/34602d17a14f306f6961863aef9c7ab9e901.pdf?_ga=2.12843442.469798984.1593548135-1379934943.1547574243

Leithwood, K., & Riehl, C. (2005). What do we already know about educational leadership? In W. A. Firestone & C. Riehl (Eds.), A new agenda for research in educational leadership (pp. 12–27). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Leithwood, K., & Sun, J. (2012). The nature and effects of transformational school leadership: A meta-analytic review of unpublished research. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(3), 387–423.

Liebowitz, D. D., & Porter, L. (2019). The effect of principal behaviors on student, teacher, and school outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 785–827.

Louis, K.S., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K.L., & Anderson, S.E. (2010). Investigating the links to improved student learning. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation. http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Investigating-the-Links-to-Improved-Student-Learning.pdf

Marks, H. M., & Louis, K. S. (1997). Does teacher empowerment affect the classroom? The implications of teacher empowerment for instructional practice and student academic performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 19(3), 245–275.

Marks, H. M., & Printy, S. M. (2003). Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 370–397.

Mascall, B., Leithwood, K., Strauss, T. and Sacks, R. (2008). The relationship between distributed leadership and teachers’ academic optimism. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(2), 214–228. https://www.hsredesign.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/09578230810863271.pdf

Murphy, J., Elliot, S. N., Goldring, E., & Porter, A. C. (2006). Learning-centered leadership: A conceptual foundation. Nashville, TN: Learning Sciences Institute, Vanderbilt University.

Murphy, J., & Hallinger, P. (1988). Characteristics of instructionally effective school districts. Journal of Educational Research, 81(3), 176–181. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270821429_Characteristics_of_Instructionally_Effective_School_Districts

Oplatka, I. (2014). The place of “social justice” in the field of educational administration: A journal-based historical overview of emergent area of study. In I. Bogotch & C. M. Shields (Eds.), International handbook of educational leadership and social (in)justice (pp. 15–35). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Osborne-Lampkin, L., Folsom J. S., & Herrington, C. D. (2015). A systematic review of the relationships between principal characteristics and student achievement (REL 2016-091). Washington, DC: Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED561940.pdf

Purkey, S. C., & Smith, M. S. (1983). Effective schools: A review. Elementary School Journal, 83(4), 427–452.

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on school outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674.

Ryan, J. (2006). Inclusive leadership and social justice for schools. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 5(1), 3–17. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/32335/1/RyanFinal.Inclusive%20Leadership%20and%20Social%20Justice%20for%20schools.pdf

Scheerens, J. (Ed.). (2012). School leadership effects revisited: Review and meta-analysis of empirical studies. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Sebastian, J., & Allensworth, E. (2012). The influence of principal leadership on classroom instruction and student learning: A study of mediated pathways to learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(4), 626–663.

Sebastian, J., Allensworth, E., Wiedermann, W., Hochbein, C., & Cunningham, M. (2019). Principal leadership and school performance: An examination of instructional leadership and organizational management. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 18(4), 591–613. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15700763.2018.1513151?needAccess=true

Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Bryk, A. S., Easton, J. Q., & Luppescu, S. (2006). The essential supports for school improvement. Chicago, IL: Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago.

Spillane, J., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. (2001). Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 23–28. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5283/8fdbf34414a8beb75fed057f4959705215de.pdf?_ga=2.55369006.469798984.1593548135-1379934943.1547574243

Spillane, J., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. (2004). Towards a theory of leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(1), 3–34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233013775_Towards_a_theory_of_leadership_practice_A_distributed_perspective

Sun, J., & Leithwood, K. (2012). Transformational school leadership effects on student achievement. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 11(4), 418–451.

Sun, J., & Leithwood, K. (2015). Direction-setting school leadership practices: A meta-analytic review of evidence about their influence. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 26(4), 499–523.

Supovitz, J., & Riggan, M. (2012). Building a foundation for school leadership: An evaluation of the Annenberg Distributed Leadership Project, 2006–2010. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=cpre_researchreports

Supovitz, J., Sirinides, P., & May, H. (2010). How principals and peers influence teaching and learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(1), 31–56.

Theoharis, G. (2007). Social justice educational leaders and resistance: Toward a theory of social justice leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 43(2), 221–258. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1033.662&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Tian, M., & Huber, S. G. (2019). Mapping educational leadership, administration and management research 2007–2016. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(2), 129–150.

Tian, M., Risku, M., & Collin, K. (2016). A meta-analysis of distributed leadership from 2002 to 2013: Theory development, empirical evidence and future research focus. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 44(1), 146–164.

Urick, A., & Bowers, A. J. (2014). What are the different types of principals across the United States? A latent class analysis of principal perception of leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50(1), 96–134. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1031.4904&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Witziers, B., Bosker, R. J., & Krüger, M. L. (2003). Educational leadership and student achievement: The elusive search for an association. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 398–425.

TITLE

SYNOPSIS

CITATION

LINK

Characteristics of Public, Private, and Bureau of Indian Education Elementary and Secondary School Principals in the United States: Results From the 2007-08 Schools and Staffing Survey. First Look.

This report presents selected findings from the school principal data files of the 2007-08 Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS). It provides the following descriptive information on school principals by school type, student characteristics, and other relevant categories: number, race/ethnicity, age, gender, college degrees, salary, hours worked, focus of work, years experience, and tenure at current school.

Battle, D. (2009). Characteristics of Public, Private, and Bureau of Indian Education Elementary and Secondary School Principals in the United States: Results From the 2007–08 Schools and Staf ng Survey (NCES 2009-323). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC.

A New Approach to Principal Preparation: Innovative Programs Share Their Practices and Lessons Learned

This paper examines a number of promising principal preparation programs to identify lessons for improving the impact of principals on student perrmance.

A new approach to principal preparation: Innovative programs share their practices and lessons learned. Rainwater Leadership Alliance, 2010.

The dilemma of pragmatics: Why schools don’t use quality team consultation practices

Research supports that school districts' prereferral consultation teams adhere less closely to quality consultation procedures and are less effective than those conducted through university research projects. This study investigated whether this finding might be due to incompatibilities between school settings and recommended team consultation practices.

Beth Doll, Kelly Haack, Stacy Kosse, Mary Osterloh, Erin Siemers & Bruce Pray (2005) The Dilemma of Pragmatics: Why Schools Don't Use Quality Team Consultation Practices, Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 16(3), 127–155.

Investigating the influence of distributed leadership on school effectiveness: A mediating role of teachers’ commitment.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the influence of distributed leadership (DL) on school effectiveness (SE) in junior secondary schools in Katsina State, Nigeria. The study also investigates if teachers’ commitment (TC) mediates the relationship between DL and SE.

Ali, H. M., & Yangaiya, S. A. (2015). Investigating the influence of distributed leadership on school effectiveness: A mediating role of teachers’ commitment. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 5(1), 163–174.

A Policymaker’s Guide: Research-Based Policy for Principal Preparation Program Approval and Licensure

Intended as a formative assessment tool, this guide provides detailed, individual state profiles and state-to-state comparisons of 8 policy areas and 21 policy criteria that support the development of effective leaders.

Anderson, E., & Reynolds, A. L. (2015). A policymaker’s guide: Research-based policy for principal preparation program approval and licensure. Charlottesville, VA: University Council for Educational Administration.

Improving School Leadership the promise of cohesive leadership system

This paper has three objectives: (1) to create set of policies and initiatives by document the actions taken by Wallace Foundation, (2) to describe how states and districts have worked together to forge more-cohesive policies and initiatives aroung school leadership, (3)to examine the hypothesis that more-cohesive systems do in fact improve school leadership.

Augustine, C. H., Gonzalez, G., Ikemoto, G. S., Russell, J., & Zellman, G. L. (2009). Improving school leadership: The promise of cohesive leadership systems. Rand Corporation.

The flip side of the coin: Understanding the school's contribution to dropout and completion.

Using a structural perspective from organizational theory, the authors review aspects of schooling associated with dropout. They then briefly review selected reform initiatives that restructure the school environment to improve student achievement and retention.

Baker, J. A., Derrer, R. D., Davis, S. M., Dinklage-Travis, H. E., Linder, D. S., & Nicholson, M. D. (2001). The flip side of the coin: Understanding the school's contribution to dropout and completion. School psychology quarterly, 16(4), 406.

Pay for Percentile

This paper proposes an incentive scheme for educators that links compensation to the ranks of their students within comparison sets.

Barlevy, G., & Neal, D. (2012). Pay for percentile. The American Economic Review, 102(5), 1805-1831.

Characteristics of Public and Private Elementary and Secondary School Principals in the United States: Results From the 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Summary, First Look

The Characteristics of Public and Private Elementary School Principals in the United States is a subsection of the NCES 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS). It provides descriptive statistics on K-12 school principals in areas such as: race, gender, education level, salary, experience, and working conditions.

Bitterman, A., Goldring, R., Gray, L., Broughman, S. (2014).Characteristics of Public and Private Elementary and Secondary School Principals in the United States:Results From the 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Summary, First Look. IES, National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education

Assertive supervision: Building involved teamwork.

This well-written book on assertiveness clearly describes the non assertive, assertive, and aggressive styles of supervision. Each chapter provides numerous examples, practice exercises, and self-tests. The author identifies feelings and beliefs that support aggressiveness, non aggressiveness, or non assertiveness which help the reader "look beyond the words themselves."

Black, M. K. (1991). Assertive Supervision-Building Involved Teamwork. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 22(5), 224-224.

The effects of integrated transformational leadership on achievement.

Greater understanding about how variables mediate the relationship between leadership and achievement is essential to the success of reform efforts that hold leaders accountable for student learning. This multi-source, quantitative study tests a model of integrated transformational leadership including three important school mediators.

Boberg, J. E., & Bourgeois, S. J. (2016). The effects of integrated transformational leadership on achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 54(3), 357–374.

Effects of the Missouri Career Ladder program on teacher mobility.

This paper seeks to estimate the effect that Career Leader (CL) program has had on teachers’ career decisions, specifically their decisions to stay in a specific school district or to remain in the teaching field.

Booker, K., & Glazerman, S. (2009). Effects of the Missouri Career Ladder program on teacher mobility. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507470.pdf

The instructional management role of the principal.

This review of related literature and research prompted the development of a framework for understanding the role of the principal as an instructional manager. A number of links between school-level variables and student learning are proposed. The discussion includes consideration of instructional organization, school climate, influence behavior, and the context of principal management.

Bossert, S. T., Dwyer, D. C., Rowan, B., & Lee, G. V. (1982). The instructional management role of the principal. Educational Administration Quarterly, 18(3), 34–64.

Progress Over a Decade in Preparing More Effective School Principals

Over the past 10 years, the Southern Regional Education Board has helped states and public universities across the region evaluate their state policies for preparing school principals who are leaders of instruction. This benchmark report reviews the past decade and looks at 10 learning-centered leadership indicators to gauge how far states have come and how far they need to go in selecting, preparing and supporting leaders of change.

Bottoms, G., Egelson, P., & Bussey, L. H. (2012). Progress over a decade in preparing more effective school principals. Atlanta, GA: Southern Regional Education Board.

Toward an evolving conceptualization of instructional leadership as leadership for learning: Meta-narrative review of 109 quantitative studies across 25 years.

The purpose of this paper is to present a comprehensive review of 25 years of quantitative instructional leadership research, up through 2013, using a nationally generalizable data set.

Boyce, J., & Bowers, A. J. (2018). Toward an evolving conceptualization of instructional leadership as leadership for learning: Meta-narrative review of 109 quantitative studies across 25 years. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(2), 161–182.

Equality and justice for all? Examining race in education research.

Although the scholarship on race in education is vast, the authors attempt to review some of the most pressing and persistent issues in this chapter. They also suggest that the future of race scholarship in education needs to be centered not on equality but rather on equity and justice.

Brayboy, B. M. J., Castagno, A. E, & Maughan, E. (2007). Equality and justice for all? Examining race in education research. Review of Research in Education, 31(1), 159–194.

Developing and empowering leaders for collective school leadership: Introduction to special issue.

The articles in this special issue emerged from papers presented by the authors during a symposium at an annual meeting of the University Council of Educational Administration (UCEA). The authors’ intent then and now is to shed light on the perceptions, preparation, practices, and impact of teacher leaders in schools through presenting reports of research on leadership development conducted in diverse states and for diverse purposes.

Browne-Ferrigno, T. (2016). Developing and empowering leaders for collective school leadership: Introduction to special issue. Journal of Research in Leadership Education, 11(2), 151-157.

Modeling the influence of school leaders on student achievement: How can school leaders make a difference?

The aim of this study was to examine the means by which principals achieve an impact on student achievement.

Bruggencate, G. T., Luyten, H., Scheerens, J., & Sleegers, P. (2012). Modeling the influence of school leaders on student achievement: How can school leaders make a difference? Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(4), 699–732. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258132484_Modeling_the_Influence_of_School_Leaders_on_Student_Achievement_How_Can_School_Leaders_Make_a_Difference

Laying the foundation for successful school leadership

Districts and states establish minimum eligibility requirements for individuals serving as principals in public schools. The intent of these requirements—which include mandated degrees, prior teaching and/or administrative experience, and certifications—is to ensure a minimum quality standard in the principal candidate pool.

Burkhauser, S., Gates, S. M., Hamilton, L. S., Li, J., & Pierson, A. (2013). Laying the foundation for successful school leadership. RAND.

Leadership and management development in education.

This article revisits the concepts of leadership and management, examines the impact of the ERA on management practice in schools and colleges, and discusses the notion of managerialism.

Bush, T. (2008). Leadership and management development in education. London, UK: SAGE Publications. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1741143207087777

Distributed leadership in action: Leading high-performing leadership teams in English schools

Heroic models of leadership based on the role of the principal have been supplemented by an emerging recognition of the value of ‘distributed leadership’. The work of effective senior leadership teams (SLTs) is an important manifestation of distributed leadership, but there has been only limited research addressing the relationship between this model and leadership teams in education.

Bush, T., & Glover, D. (2012). Distributed leadership in action: Leading high-performing leadership teams in English schools. School leadership & management, 32(1), 21-36.

Investigating connections between distributed leadership and instructional change.

In this chapter of "Distributed leadership: Different perspectives" the authors take a small step towards addressing such questions by investigating the association between the distribution of leadership to teachers and instructional change in schools.

Camburn, E., & Han, S. W. (2009). Investigating connections between distributed leadership and instructional change. In A. Harris (Ed.), Distributed leadership: Different perspectives (pp. 25–45). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

The effects of school-based decision-making on educational outcomes in low- and middle-income contexts: a systematic review

This review assesses the effectiveness of school-based curricula, finance, management, and teacher’s decision-making. This report has implications for the impact of charter schools, as the primary intervention in this model is local control. The report finds limited evidence of the effectiveness of these reforms, especially from low-income countries.

Carr-Hill, R., Rolleston, C., Pherali, T., & Schendel, R. (2014). The effects of school-based decision making on educational outcomes in low-and middle-income contexts: A systematic review.

Is school value added indicative of principal quality?

In a time when public schools continue to be scrutinized, school leadership never mattered more in order to exercise school reform. This qualitative study examined how five principals working in an urban school district perceived their evaluation and how it contributed to their practice.

Chacon-Robles, B. (2018). Improving instructional leadership: A multi-case study perspectives on formal evaluations. The University of Texas at El Paso.

A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams

A multilevel model of leadership, empowerment, and performance was tested using a sample of 62 teams, 445 individual members, 62 team leaders, and 31 external managers from 31 stores of a Fortune 500 company. Leader-member exchange and leadership climate-related differently to individual and team empowerment and interacted to influence individual empowerment.

Chen, G., Kirkman, B. L., Kanfer, R., Allen, D., & Rosen, B. (2007). A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 331–346.

Navigating comprehensive school change: A guide for the perplexed

Thorough and comprehensive, this book offers essential information about how to form leadership teams, identify high stakes problems, build commitment, create a school-wide vision and establish school-wide goals, handle setbacks, maintain the vision and sustain change, evaluate and assess comprehensive school change.

Chenoweth, T. G., & Everhart, R. B. (2002). Navigating comprehensive school change: A guide for the perplexed. Eye on Education.

Principal leadership in new teacher induction: Becoming agents of change

This small-scale pilot study investigated the role of school principals in the induction of new teachers in Ontario, Canada.

Cherian, F., & Daniel, Y. (2008). Principal Leadership in New Teacher Induction: Becoming Agents of Change. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 3(2), 1-11.

Learning to lead together: The promise and challenge of sharing leadership.

Through real-life single and multiple case studies, This book addresses how principals and their staffs struggle with the challenge of shared leadership, how they encourage teacher growth and development, and how shared leadership can lead to higher levels of student learning.

Chrispeels, J. H. (Ed.). (2004). Learning to lead together: The promise and challenge of sharing leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Opportunities suspended: The devastating consequences of zero tolerance and school discipline policies. Report from a national summit on zero tolerance.

This is the first comprehensive national report to scrutinize the impact of strict Zero Tolerance approach in the America public school. This report illustrate that Zero Tolerance is unfair, is contrary to developmental needs of children, denies children educational opportunities, and often results in the criminalization of children.

Civil Rights Project. (2000). Opportunities suspended: The devastating consequences of zero tolerance and school discipline policies.

Effective schools and school improvement: A comparative analysis of two lines of inquiry

The history and the intra-and inter-literature consensus of these two lines of inquiry will be examined in this review. The purpose is to determine whether the findings and generalizations of those bodies of research can be used conjointly in order to understand how schools strive to change to attain more effective instructional outcomes.

Clark, D. L., Lotto, L. S., & Astuto, T. A. (1984). Effective schools and school improvement: A comparative analysis of two lines of inquiry. Educational Administration Quarterly, 20(3), 41–68.

Impacts of the Teach for America investing in innovations scale-up

Teach For America (TFA) is a nonprofit organization that seeks to improve educational opportunities for disadvantaged students by recruiting and training teachers to work in low income schools. The program uses a rigorous screening process to select college graduates and professionals with strong academic backgrounds and

leadership experience and asks them to commit to teach for two years in high-needs schools.

Clark, M. A., Isenberg, E., Liu, A. Y., Makowsky, L., & Zukiewicz, M. (2015). Impacts of the Teach For America investing in innovation scale-up. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research.

Rethinking principal evaluation: A new paradigm informed by research and practice

As the federal government urges states and districts to create principal evaluation systems, largely linked to student achievement, it’s also time that principals be part of the conversation. Without the inclusion of the expertise of school and instructional leaders, the new evaluation systems created across the country may not necessarily be improved or attain desired results, and, as a result, principals may not view feedback from these new evaluation systems as informative for improvement of their practice or their schools.

Connelly, G., & Schooley, M. (2013). National Association of Elementary School Principals. Leadership Matters: What the Research Says About the Importance of Principal Leadership.

Why teams don’t work

The belief that working in teams makes us more creative and productive is so widespread that when faced with a challenging new task, leaders are quick to assume that teams are the best way to get the job done. Getting agreement is the leader’s job, and they must be willing to take great personal and professional risks to set the team’s direction. And if the leader isn’t disciplined about managing who is on the team and how it is set up, the odds are slim that a team will do a good job.

Coutu, D., & Beschloss, M. (2009). Why teams don’t work. Harvard business review, 87(5), 98-105.

The flat world and education: How America’s commitment to equity will determine our future.

The authors arguing that the United States needs to move much more decisively than it has in the last quarter-century to establish a purposeful, equitable education system that will prepare all our children for success in a knowledge-based society.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). The flat world and education: How America’s commitment to equity will determine our future. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Professional learning in the learning profession: A status report on teacher development in the United States and abroad.

This report examines practices in teacher and principal development in the United States in 2010. It looks at ineffective approaches as well as those models that show promise for improving educator and student performance.

Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R. C., Andree, A., Richardson, N., & Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession. Washington, DC: National Staff Development Council.

The implementation and replication of the distributed leadership program: More lessons learned and beliefs confirmed

The first paper describes the theory of action and essential components of the DL Program. It presents a brief overview of how the DL Program was initially conceived and operationalized, how it was replicated for its second and current implementation effort, and lessons learned across implementations.

DeFlaminis, J. A. (2013). The implementation and replication of the distributed leadership program: More lessons learned and beliefs confirmed. In annual meeting of the American educational research association, San Francisco, California.

Race to the Top Program: Executive summary

Race to the Top will reward States that have demonstrated success in raising student achievement and have the best plans to accelerate their reforms in the future. These States will offer models for others to follow and will spread the best reform ideas across their States, and across the country.

Department of Education (ED). (2009). Race to the Top program: Executive summary. ERIC Clearinghouse.

Appraising principal evaluation and development: Current research and future directions.

In the past decade, nearly all states have revised their principal evaluation policies, prompting school districts across the country to rethink how they are evaluating school leaders. The new principal evaluation systems that emerge out of these policy reforms often couple increased accountability with a greater emphasis on development in an effort to spur continuous improvement in school leadership practices.

Donaldson, M., Mavrogordato, M., Youngs, P., & Dougherty, S. (2020). Appraising Principal Evaluation and Development: Current Research and Future Directions. Exploring Principal Development and Teacher Outcomes, 56-68.

Leadership Models

This review highlights major models that have been influential in the field and discusses evidence for their efficacy in explaining school leaders’ influence.

Donley, J., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, (2020). Leadership Models. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/quality-leadership-leadership-models

Leading together: Teachers and administrators improving student outcomes.

Leadership is what is done, not who is doing it. The leadership work blurs the lines between teachers and administrators. Leading Together introduces a collective approach to progress, process, and programs to help build the conditions in which strong leadership can flourish and student outcomes improve. Explore the Collective Leadership Development Model for School Improvement.

Eckert, J. (2017). Leading together: Teachers and administrators improving student outcomes. Corwin Press.

Collective leadership development: Emerging themes from urban, suburban, and rural high schools.

Applying an analytic model to better understand collective leadership development, this study examines three high schools: one urban, one suburban, and one rural. Each school's unique structure and context tests the model's explanatory power.

Eckert, J. (2019). Collective leadership development: Emerging themes from urban, suburban, and rural high schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 55(3), 477–509.

Teaming: How organizations learn, innovate, and compete in the knowledge economy

New breakthrough thinking in organizational learning, leadership, and change. Continuous

improvement, understanding complex systems, and promoting innovation are all part of the

landscape of learning challenges today's companies face. Amy Edmondson shows that

organizations thrive, or fail to thrive, based on how well the small groups within those

organizations work.

Edmondson, A. C. (2012). Teaming: How organizations learn, innovate, and compete in the knowledge economy. John Wiley & Sons.

Building strong school leadership teams to sustain reform.

Effective Instructional Leadership Teams can be integral to helping underperforming schools strengthen their leadership, professional learning systems and core instruction.

Edwards, B., & Gammell, J. (2016). Building strong school leadership teams to sustain reform. Leadership, 45(3), 20-22. https://www.shastacoe.org/uploaded/Haylie_Blalock/Building-Strong-School-Leadership-Teams-to-Sustain-Reform.pdf

The Every Student Succeeds Act, state efforts to improve access to effective educators, and the importance of school leadership

Our primary purpose is to examine the degree to which state equity plans identify the distribution of principals and principal turnover as factors influencing three leadership mechanisms that affect student access to effective teachers—namely, hiring of teachers, building instructional capacity of teachers, and managing teacher turnover.

Fuller, E. J., Hollingworth, L., & Pendola, A. (2017). The Every Student Succeeds Act, state efforts to improve access to effective educators, and the importance of school leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 53(5), 727-756.

Planning for the Future: Leadership development and succession planning in education

This article reviews the research and best practices on succession planning in education as well as in other sectors. The authors illustrate how forward-thinking superintendents can partner with universities and other organizations to address the leadership challenges they face by creating strategic, long-term, leadership growth plans that build leadership capacity and potentially yield significant returns in improved student outcomes.

Fusarelli, B. C., Fusarelli, L. D., & Riddick, F. (2018). Planning for the future: Leadership development and succession planning in education. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 13(3), 286–313.

A systematic review of studies of leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014.

The purpose of this study is to reveal the extent to which different leadership models in education are studied, including the change in the trends of research on each model over time, the most prominent scholars working on each model, and the countries in which the articles are based.

Gümüş, S., Bellibaş, M. S., Esen, M., & Gümüş, E. (2018). A systematic review of studies of leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 46(1), 25–48.

Radical recentering: Equity in educational leadership standards.

In this article, the authors put forth a new set of standards with equity at the core. They seek to advance the conversation about why standards centered on equity are needed—particularly in light of a proposed standards refresh—and what implications would follow from equity-focused standards.

Galloway, M. K., & Ishimaru, A. M. (2015). Radical recentering: Equity in educational leadership standards. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(3), 372–408.

Using State-Level Policy Levers to Promote Principal Quality

Effective school leaders, particularly principals, are associated with better outcomes for students and schools. Principals help set school vision and culture, which support teacher effectiveness and ultimately can help improve student achievement.

Gates, S. M., Woo, A., Xenakis, L., Wang, E. L., Herman, R., Andrew, M., & Todd, I. (2020). Using State-Level Policy Levers to Promote Principal Quality: Lessons from Seven States Partnering with Principal Preparation Programs and Districts. RAND Principal Preparation Series. Volume 2. Research Report. RR-A413-1. RAND Corporation. PO Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138.

The best laid plans: Pay for performance incentive programs for school leaders

In an era of heightened accountability and limited fiscal resources, school districts have sought novel ways to increase the effectiveness of their principals in an effort to increase student proficiency. To address these needs, some districts have turned to pay-for- performance programs, aligning leadership goals with financial incentives to motivate and direct leadership efforts. Pay-for-performance strategies have been applied to schools for decades.

Goff, P., Goldring, E., & Canney, M. (2016). The best laid plans: Pay for performance incentive programs for school leaders. Journal of Education Finance, 42(2), 127-152.

The convergent and divergent validity of the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the ongoing dialog of whether and how instructional leadership is distinguished conceptually from general leadership notions, such as charisma, and to continue the ongoing psychometric research on the The Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED) by examining its convergent and divergent validity. The authors hypothesize that the VAL-ED will be highly correlated with another measure of instructional leadership, but will be weakly correlated with more general measures of leadership that are rooted in personality theories.

Goldring, E., Cravens, X., Porter, A., Murphy, J., & Elliott, S. (2015). The convergent and divergent validity of the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED): Instructional leadership and emotional intelligence. Journal of Educational Administration.

How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research

School leadership matters for school outcomes, including student achievement. This assumption has become commonplace since the publication of the highly influential Wallace Foundation–commissioned report by Leithwood and colleagues in 2004. Policymakers and researchers often quote the report's main conclusion that “leadership is second only to classroom instruction among all school-related factors that contribute to what students learn at school”.

Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools.

Effective Instructional Time Use for School Leaders: Longitudinal Evidence from Observations of Principals

This study examines principals’ time spent on instructional functions. The results show that the traditional walk-through has little impact, but principals provide coaching, evaluation, and focus on educational programs can make a difference.

Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., & Master, B. (2013). Effective Instructional Time Use for School Leaders: Longitudinal Evidence from Observations of Principals. Educational Researcher, 42(8), 433-444.

The new work of educational leaders: Changing leadership practices in an era of school reform.

The author provides a new framework for understanding leadership practice. The work of leaders will increasingly be shaped by three overriding but contradictory themes: design; distribution; and disengagement. These are the `architecture' of school and educational leadership.

Gronn, P. (2003). The new work of educational leaders: Changing leadership practices in an era of school reform. London: Paul Chapman.

Leading teams: Setting the stage for great performances

Teams have more talent and experience, more diverse resources, and greater operating flexibility than individual performers. J. Richard Hackman, one of the world's leading experts on group and organizational behavior, argues that the answer to this puzzle is rooted in flawed thinking about team leadership.

Hackman, J. R., & Hackman, R. J. (2002). Leading teams: Setting the stage for great performances. Harvard Business Press.

Considerations of administrative licensure, provider type, and leadership quality: Recommendations for research, policy, and practice

This article reviews U.S. administrative licensure regulations, focusing on type of school leader licensure, provider types, and leadership quality. Licensure obtained through university-based and alternative routes is examined.

Hackmann, D. G. (2016). Considerations of administrative licensure, provider type, and leadership quality: Recommendations for research, policy, and practice. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 11(1), 43-67.

Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away.

This paper ties together evidence drawn from several extensive reviews of the educational leadership literature that included instructional leadership as a key construct.

Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3), 221–239. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228633330_Instructional_Leadership_and_the_School_Principal_A_Passing_Fancy_that_Refuses_to_Fade_Away