Why Education Practices Fail

“Implementation, where great ideas go to die”

—Ronnie Detrich

Table of Contents

Decision-Making Failures

Implementation Failures

Monitoring Failures

When many educators hear the term “evidence-based,” they think of research based on sound science. Conventional wisdom suggests that once we know what works, it is a simple matter of applying research-based interventions in real-world settings and then sitting back and watching schools reap the benefits. Sadly, that is not how performance improvement happens. Successful innovation requires hard work and adherence to the science of implementation. The education landscape is strewn with interventions that have ample supporting research but fail when applied in school settings. On the other hand, abundant programs with poor or no supporting research are adopted and continue to be implemented despite poor outcomes.

Something is missing in how schools raise student outcomes. How can it be that so much quality research is producing so little? Since 1990, the United States has spent vast sums on education interventions that failed (Yeh, 2007). Recent data suggests 43 million adults in the United States are functionally illiterate (U.S. Department of Education, 2019).

What lessons can be learned from our mistakes and past attempts to reform education? This paper examines a range of education failures: common mistakes in how new practices are selected, implemented, and monitored. The goal is not a comprehensive listing of all education failures but rather to provide education stakeholders with an understanding of the importance of vigilance when implementing new practices.

Failures in Decision Making, Implementation, and Monitoring

The third decade of the 21st century is a period of great skepticism and distrust of experts. Objectivity has been replaced by subjectivity (McIntyre, 2019). It is not surprising that, in such an environment, many in the public question the validity of an evidence-based approach. This is especially true given stagnant student performance on standardized tests; for example, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) math and reading scores and decades of failed school reform (U.S. Department of Education, 2020).

Unfortunately, too often the wrong lessons have been learned from failed school reform. Educators not trained in an evidence-based process often misunderstand how science works. Science is messy. It is an incremental process of building a knowledge base over time to achieve greater clarity until a preponderance of evidence validates or refutes a practice. Science is not a magic bullet. No quick fix exists, and science has imperfections. Still, over the past 200 years, science has proved to be amazingly reliable and the most effective method for understanding and explaining how the world works (Oreskes, 2019).

Decision-Making Failures

Poor decisions happen for a variety of reasons. Failures commonly occur when schools choose practices that are not evidence based, not matched to the conditions identified in the research, and incompatible with the values of the school, and when the selection process doesn’t involve critical stakeholders.

Practices Without Evidence (Whole Language): Despite decades of quality research on the most effective ways to teach reading (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000; Walsh, Glaser, & Dunne Wilcox, 2006), in the 1980s California adopted a reading approach known as whole language, based on the belief that reading comes as naturally to humans as does speaking (Hanford, 2019; Sender, 2019). It relies on the assumption that allowing students to select their materials will encourage a love of reading and thus boost reading proficiency. However, the practice lacked a strong evidence base. It failed to include core components of teaching reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. This statewide intervention proved to be a failure, leaving California students far behind other states in reading achievement (Lemann, 1997; Moats, 2007). By the middle of the 1990s, California had abandoned whole language. Unfortunately, the story does not end there as the approach has come back in the guise of balanced reading (Moats, 2000).

Lesson: When whole language was adopted, California did not have evidence-based protocols to vet practices. It is essential to follow the research by establishing policies and protocols for assessing and adopting evidence-based practices, and for avoiding interventions that have an appealing backstory but run counter to the best available evidence.

Publication Bias: Evidence-based education practitioners rely on peer-reviewed research published in journals. That works well for the most part, but the system has problems. Publication bias can result in a reliance on inaccurate information that negatively impacts critical education decisions. Bias occurs because studies with positive findings are more likely to be published—and published more quickly—than studies that find negative outcomes for interventions (Ravid, 2019). The fact is that negative findings aren’t as attention grabbing to publishers or the public. However, for effective decision making, knowing what doesn’t work is as important as knowing what works (Chow & Ekholm, 2018; Torgerson, 2006).

Lesson: Any individual study or meta-analysis must be scrutinized for bias. When making important decisions, educators need to be aware of publication bias. To avoid selecting the wrong practice, practitioners must also search for unpublished reports as well as those found in published journals to increase the knowledge base on what practices do not work.

Conflict of Interest: In research, a conflict of interest refers to a situation of financial, commitment (e.g., employer expectations), or other personal considerations (e.g., career advancement), or when the appearances of compromising a researcher’s professional judgment are evident in conducting or reporting research (University of California, San Francisco, 2013). Conflicts of interest are common and recognized in federal regulations, state laws, and university policies. Better disclosure of conflicts of interest is needed to increase decision makers’ confidence in selecting practices. One study in the field of medicine found 100% of studies supporting specific drug interventions had financial relationships with the drug companies involved. In contrast, only 43% of authors of reports critical of the drugs had potential conflicts of interest with drug companies (Stelfox, Chua, O’Rourke, & Detsky, 1998).

Lesson: To minimize the negative impacts of conflicts of interest, researchers should disclose any conflicts and manage potential conflicts (Resources for Research Ethics Education, 2001). Consumers of research need to identify potential conflicts of interest to avoid using biased results when making decisions (Romain, 2015). An area of concern that should trigger a red flag is research funded or produced by an advocacy organization. Other types of conflicts of interest are more challenging for educators to identify. Educators need to rely on organizations such as What Works Clearinghouse and the Campbell Collaboration, which have the resources to assist in vetting studies.

Relying on a Single Study: A sufficient quantity of evidence to determine the efficacy of a practice is the cornerstone of an evidence-based education model. The best decisions derive from comparing the results of many studies that examine the same phenomenon. One study does not offer conclusive evidence of the effectiveness of a practice (Rosenthal & DiMatteo, 2002). Scientists gain confidence in their knowledge by replicating findings through multiple studies conducted by independent researchers over time, to show that results were not a fluke or due to an error. The benchmark for analyzing numerous studies on the same topic is meta-analysis, a literature review that integrates individual studies of a single subject using statistical techniques to combine the results into an overall effect size. A meta-analysis is the most objective method for comparing the results of many studies (Slavin, 1984).

A study published in 1993 concluded that listening to Mozart boosted the intelligence of college students (Rauscher, Shaw, & Ky, 1993). This single study was widely reported in the mainstream media. As the finding spread, a single study about the impact of college students listening to classical music went viral as the public embraced the notion that even babies would benefit from listening to classical music. Subsequent analysis showed that over a dozen subsequent studies failed to verify the original study’s results (Krakovsky, 2005).

Lesson: Avoid making conclusions from just one paper. Evaluate research findings reported in popular media by examining the source material. Replicating a study is the best way to increase confidence in the conclusions derived from the research.

Implementation Failures

Knowing what to do is not the same as being able to do it. Implementing evidence-based practices in real-world settings comes with significant challenges. The past 15 years have seen remarkable progress in creating a science to address these hurdles. Implementation science is the study of methods and strategies that facilitate the use of research and evidence-based practice into the everyday routines of practitioners and policymakers (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). It manages critical factors such as need, fit, capacity, evidence, usability, and supports to achieve sustainable change (Blase, Kiser, & Van Dyke, 2013).

Structural Interventions: A frequent reason why education interventions fail is the adoption of structural interventions. A structural intervention is any practice that promises a simple fix to a complex problem but does not require specific changes in how people perform their jobs. A structural intervention is analogous to a Hollywood façade; it looks real at first glance but has only the pretense of being real.

Examples of popular structural interventions include accountability (high-stakes testing to hold schools accountable for improved student performance), charter schools, and class-size reduction (Yeh, 2007). Each intervention suggests an appealing solution to a genuine problem, but they share a common flaw: They offer the appearance of change without proposing concrete steps for how implementers are to deliver on the promise. When a solution does not specify how people are to perform, little will likely change.

For example, when accountability permits school principals to hold teachers responsible but teachers are not told how to raise test scores, the intervention will fail. Likewise, if the proponents of charter schools promote local control as a means to increase student achievement, but no standard curriculum or pedagogy exists that differs from public schools, the charter schools will likely perform no better than public schools (Yeh, 2007). Similarly, the promise of smaller class sizes evaporates when teachers do not adapt teaching methods to take advantage of smaller student-teacher ratios (Yeh, 2007). Meaningful change requires specific guidance for how people are to do their jobs; without it, the result is the appearance of reform and a continuation of the status quo.

Teacher induction is an example of a structural intervention, a model with great potential, but never realized. Teacher induction was conceived to support new and beginning teachers to become competent and effective classroom teachers. Induction programs support new teachers and facilitate their socialization into the profession and school. Most educators view these programs as useful ways to improve retention, instructional skills, and, ultimately, student performance. Despite spending an estimated $1,660 to $6,605 per teacher per year, induction has failed to accomplish these educational goals (Villar, Strong, & Fletcher, 2007). As is characteristic of structural interventions, there is no single method of conducting induction (Maheady & Jabot, 2012). Few oversight mechanisms exist to assess how funds are spent, what curriculum is adopted, or how teachers are trained. After 20 years of induction in the United States, there is little to show for this massive investment in time and money. As long as teacher induction remains open to interpretation by all who implement the model, the effective integration of new teachers into schools will suffer.

Lesson: Induction can work, but only under two conditions: (1) when staff development is standardized and delivered consistently across all participants, and (2) when coaching, the most effective method of training, is incorporated into the program.

Ineffective Staff Development: Professional development is an integral strategy for schools to improve teacher performance (Goldring, Gray, & Bitterman, 2013). Almost all (99%) teachers participate in professional development (Goldring et al., 2013). An analysis found that teachers spend up to 10% of their school year (19 days) engaged in training (TNTP, 2015). The American education system values in-service training to improve teacher performance, spending an average of $18,000 annually per teacher. Schools invest extensively in teacher induction for new teachers, supplemented with in-service training throughout their careers. But what constitutes the essential components of productive professional development?

Answering this question is crucial to ensure that the investment in professional development has an impact on how teachers teach and whether or not students benefit from these efforts. Multiple reviews of studies have identified features shared by high-quality professional development: content focus, active learning, collaboration, models of effective practice, coaching and expert support, feedback, and sustained duration (Cleaver, Detrich, & States, 2018).

Like many practices, professional development has failed to deliver on its promise. Unfortunately, common training methods such as workshop sessions that rely on passive didactic techniques (lecturing or reading) are unproductive and have shown minimal or no impact on a teacher’s use of the practices in the classroom (Penuel, Fishman, Yamaguchi, & Gallagher, 2007). However, teachers do benefit from professional development when training incorporates coaching-based clinical training. Coaching produces best results when teachers practice skills on students in a classroom setting and receive feedback from the coach as a component of the activity (Cleaver et al., 2018; Joyce & Showers, 2002).

Professional development effectiveness especially suffers if administrators do not assess whether the teachers are implementing the training correctly in the classroom. Research shows that teacher in-service training is frequently offered as a series of disconnected workshops, delivering instruction seemingly irrelevant to teachers’ needs, and employing inferior training techniques. Most alarming is the lack of follow-up to assess if the training works as intended. Under such circumstances, teachers quickly learn that they can go about their business as usual.

Lesson: Professional development can have a significant impact, but if teachers are to benefit, training must be for more than mere paper compliance. In-service training needs to incorporate the best evidence for training and follow a well-designed implementation plan.

Monitoring Failures

Because no intervention will be universally effective, frequent monitoring of results is necessary so that decisions can be made on how to adapt and improve instruction. Infrequent monitoring wastes resources and time when ineffective interventions are left in place too long. Monitoring how well an intervention is implemented (treatment integrity) is also essential to know whether the intervention is ineffective or just implemented poorly. Understanding the quality of implementation allows practitioners to make data-informed judgments about the effects of an intervention. Making judgments about impact in the absence of objective information forces educators to make blind assumptions on how to best proceed. In some instances, poor data result in discontinuing interventions that could be effective if implemented properly, leading educators to abandon practices that might have produced positive outcomes in the future.

Ineffective Treatment Integrity: The increasing pressure on schools to improve student achievement has resulted in teachers being bombarded with a myriad of school reforms. As educators look for solutions to stagnant student performance, demand has increased for schools to embrace evidence-based practices. These practices, vetted using rigorous research methods, are intended to increase confidence in the causal relationship between a practice and student outcomes. But for practices to work as studies predict, they must be implemented with integrity. Treatment integrity, also referred to as treatment fidelity, is defined as the extent to which an intervention is executed as designed, and the accuracy and consistency with which it is implemented (Detrich, 2014; McIntyre, Gresham, DiGennaro, & Reed, 2007).

Inattention to treatment integrity is a primary reason for failure during implementation. Research suggests that practices are rarely implemented as designed (Hallfors & Godette, 2002). Despite solid evidence of a relationship between effectiveness of a practice and the integrity with which is implemented, only in the past 20 years have systematic efforts focused on how practitioners can influence the quality of treatment integrity (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Fixsen et al., 2010).

When an intervention has strong empirical support and is implemented with high integrity, the probability is high that positive outcomes can be attributed to the intervention. On the other hand, poor implementation of a practice raises the possibility that the issue is with the quality of implementation and not with the practice itself (Fixsen et al., 2005). But if the integrity of the implementation is not monitored, it is impossible to know which of these cases are true.

Lesson: For the best chance of producing positive educational outcomes for all children, two conditions must be met: (a) adopting effective empirically supported (evidence-based) practices and (b) implementing those practices with sufficient quality that they make a difference (treatment integrity) (Detrich, 2014). Both are necessary as neither on its own is sufficient to result in positive outcomes. Knowing how well a practice is implemented is essential if educators are to make informed decisions on how to proceed when implementing new practices.

Ineffective Teacher Evaluations: A teacher’s skills, strengths, and abilities influence student learning as much as student background (Wenglinsky, 2002). Put another way, teachers matter; effective teachers contribute to positive student outcomes and achievement, making it crucial to understand how effective teachers teach (Cleaver et al., 2018). Research suggests that principals are the critical link in ensuring that a school has highly effective teachers. A recent meta-analysis of 51 studies found moderate to large effect sizes for the impact of principal behaviors and competencies on student achievement, teacher well-being, instructional practices, and school organizational health (Liebowitz & Porter, 2019).

Principals exert the greatest influence on student learning and achievement by developing the skills of teachers (Donley, Detrich, States, & Keyworth, 2020; Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008). A principal’s impact on a teacher’s instructional competence is proportional to the principal’s knowledge of how well the teacher performs his or her teaching duties. A basic definition of “teacher evaluation” is the process that schools use to review teacher performance and effectiveness in the classroom (Sawchuk, 2015). This knowledge is best acquired when principals engage in formal and informal teacher evaluation (summative and formative teacher assessment).

Teacher evaluation serves two purposes: (1) performance improvement and (2) accountability. Evaluations are conceived as a way to ensure teacher quality and promote professional learning to improve future performance (Danielson, 2010). An assessment provides teachers with information that can enhance their practice and serve as a starting point for professional development; for example, using data from teacher evaluations to set a plan of study for professional learning community (PLC) meetings. A teacher evaluation provides accountability when information gained from the assessment guides decisions regarding bonuses, firing, and other human resource issues (Santiago & Benavides, 2009). Well-designed evaluation systems involve understanding and agreeing on the inputs (e.g., the practices that define quality teaching); outputs (e.g., student achievement measures); and methods of evaluation (e.g., student assessment data, teacher observation rubrics).

Given the emphasis placed on a principal’s capacity to improve teacher performance, it is not surprising that, when surveyed, principals claimed they spent up to 70% of their working day on issues of teacher instruction (Turnbull et al., 2009). But after analyzing principals’ perception of time spent on teaching, the researchers found the actual time that principals engaged in monitoring classroom instruction activities was only 30% of the working day. Principals must assess their schedules and prioritize allocating sufficient time to address the instructional needs of teachers.

In reality, large gaps exist between how evaluations should work and how they do work. Research suggests that evaluations are failing to improve performance or act as a mechanism for holding teachers accountable. In a 2011 study, Fink and Markholt found that principals were not well trained in identifying critical dimensions of effective instruction. In this study, the researchers assessed principals’ ability to identify five dimensions of effective teaching by observing teachers conducting lessons. On the whole, principals were unable to perform better than an emerging level of competency. If principals do not have the capacity (skills and knowledge) to perform this task, it is questionable whether a large segment of principals can effectively deliver feedback that can improve instruction.

Having accurate data on teacher performance is essential if principals are to provide meaningful feedback. Research suggests that systematic observations are the method most likely to provide this information. But what are the most common data collection methods that principals employ to conduct observations? A 2012 paper looking at the actual sources of information principals relied upon found that principals were engaged only approximately 5% of the time in conducting targeted observations (Grissom, Loeb, Master, 2012). Their primary source of information was informal, unscheduled walkthroughs, a much less effective technique.

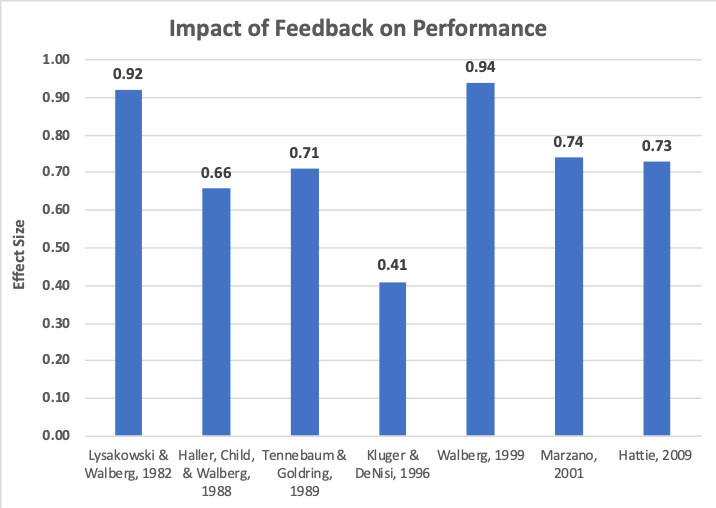

Figure 1. General impact of feedback on performance

Feedback is one of the most powerful tools available to principals for improving performance. Key to its effective use are having evaluators competent in delivering feedback, and frequent and systematic sampling of a teacher’s instructional skills (Fink and Markholt, 2011; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). As is common in structural interventions, it is not merely conducting evaluations that makes a difference; it is how teachers are assessed that produces meaningful results.

Lesson: To improve teacher evaluation requires more effective principal training in the use of feedback and in implementing systems for delivering frequent feedback that includes targeted formative observations of teachers teaching.

Conclusion

Failed educational interventions happen often. Learning from these missed opportunities is a part of operating schools. Ample evidence is available on how to avoid many of the most common obstacles to achieving success in the classroom. Following evidence-based protocols for making decisions, implementing sustainable practices, and monitoring the effects of interventions offers educators the most viable and cost-effective way to maximize educational outcomes for students.

Citations

Blase, K., Kiser, L., & Van Dyke, M. (2013). The hexagon tool: Exploring context. Chapel Hill, NC: National Implementation Research Network, FPG Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Chow, J. C., & Ekholm, E. (2018). Do published studies yield larger effect sizes than unpublished studies in education and special education? A meta-review. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 727–744.

Cleaver, S., Detrich, R. & States, J. (2018). Teacher coaching overview. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/teacher-evaluation-teacher-coaching

Danielson, C. (2010). Evaluations that help teachers learn. Educational Leadership, 68(4), 35–39. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/dec10/vol68/num04/Evaluations-That-Help-Teachers-Learn.aspx

Detrich, R. (2014). Treatment integrity: Fundamental to education reform. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 13(2), 258–271.

Donley, J., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, (2020). Principal competencies. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/principal-competencies-research

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3-4), 327–350.

Fink, S., & Markholt, A. (2011). Leading for instructional improvement: How successful leaders develop teaching and learning expertise. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (FMHI #231). Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network.

Fixsen, D. L., Blase, K. A., Duda, M. A., Naoom, S. F., & Van Dyke, M. (2010). Implementation of evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Research findings and their implications for the future.

Goldring, R., Gray, L., & Bitterman, A. (2013). Characteristics of public and private elementary and secondary school teachers in the United States: Results from the 2011–12 schools and staffing survey (NCES 2013-314). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., & Master, B. (2012). What is effective instructional leadership? Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, Baltimore, MD.

Haller, E. P., Child, D. A., & Walberg, H. J. (1988). Can comprehension be taught? A quantitative synthesis of “metacognitive” studies. Educational Researcher, 17(9), 5–8.

Hallfors, D., & Godette, D. (2002). Will the “principles of effectiveness” improve prevention practice? Early findings from a diffusion study. Health Education Research, 17(4), 461–470.

Hanford, E. (2019). At a loss for words: How a flawed idea is teaching millions of kids to be poor readers. APM Reports. https://www.apmreports.org/story/2019/08/22/whats-wrong-how-schools-teach-reading

Hattie, J. A. C. (2009). Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Joyce, B. R., & Showers, B. (2002). Student achievement through staff development (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284.

Krakovsky, M. (2005). Dubious “Mozart effect” remains music to many Americans’ ears. Stanford, CA: Stanford Report.

Lemann, N. (1997). The reading wars. The Atlantic Monthly, 280(5), 128–133.

Liebowitz, D. D., & Porter, L. (2019). The effect of principal behaviors on student, teacher, and school outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 785–827.

Lysakowski, R. S., & Walberg, H. J. (1982). Instructional effects of cues, participation, and corrective feedback: A quantitative synthesis. American Educational Research Journal, 19(4), 559–572.

Maheady, L., & Jabot, M. (2012). Comprehensive teacher induction: What we know, don’t know, and must learn soon! In R. Detrich, R. Keyworth, & J. States (Eds.), Advances in Evidence-Based Education, Volume 2 (pp. 65–89). Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute.

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D., & Pollock, J. E. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

McIntyre, L., (2019, May 22). How to reverse the assault on science. Scientific American. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/how-to-reverse-the-assault-on-science1/

McIntyre, L. L., Gresham, F. M., DiGennaro, F. D., & Reed, D. D. (2007). Treatment integrity of school‐based interventions with children in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 1991–2005. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(4), 659–672.

Moats, L. C. (2000). Whole language lives on: The illusion of “balanced” reading instruction. Washington, DC: DIANE Publishing.

Moats, L. (2007). Whole-language high jinks: How to tell when “scientifically-based reading instruction” isn’t. New York, NY: Thomas B. Fordham Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED498005.pdf

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: Author.

Oreskes, N. (2019). Why trust science? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Penuel, W. R., Fishman, B. J., Yamaguchi, R., & Gallagher, L. P. (2007). What makes professional development effective? Strategies that foster curriculum implementation. American Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 921–958.

Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L., & Ky, C. N. (1993). Music and spatial task performance. Nature, 365(6447), 611–611.

Ravid, R. (2019). Practical statistics for educators. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Resources for Research Ethics Education. (2001). What is a conflict of interest? San Diego, CA: University of California, San Diego. http://research-ethics.org/topics/conflicts-of-interest/

Robinson, V. M., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674.

Romain, P. L. (2015). Conflicts of interest in research: Looking out for number one means keeping the primary interest front and center. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 8(2), 122–127.

Rosenthal, R., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2002). Meta‐analysis. In J. Wixted & H. Pashler (Eds.), Stevens’ handbook of experimental psychology; Vol. 4. Methodology in experimental psychology (pp. 391–428). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Santiago, P., & Benavides, F. (2009). Teacher evaluation: A conceptual framework and examples of country practices.Paper presented at the OECD-MEXICO workshop “Towards a teacher evaluation framework in Mexico: International practices, criteria and mechanisms,” Mexico City.

Sawchuk, S. (2015). Teacher evaluation: An issue overview. Education Week, 35(3), 1–6.

Sender, R., (2019). At a loss for words: How a flawed idea is teaching millions of kids to be poor readers. APM Reports. https://www.apmreports.org/story/2019/08/22/whats-wrong-how-schools-teach-reading

Slavin, R. E. (1984). Meta-analysis in education: How has it been used? Educational Researcher, 13(8), 6–15.

States. J., (2009). The cost-effectiveness of five policies for improving student achievement. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/how-does-class-size

Stelfox, H. T., Chua, G., O'Rourke, K., & Detsky, A. S. (1998). Conflict of interest in the debate over calcium-channel antagonists. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(2), 101–106.

Tenenbaum, G., & Goldring, E. (1989). A meta-analysis of the effect of enhanced instruction: Cues, participation, reinforcement and feedback and correctives on motor skill learning. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 22(3), 53–64.

TNTP (2015). The mirage: Confronting the hard truth about our quest for teacher development. New York, NY: Author. http://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP-Mirage_2015.pdf

Torgerson, C. J. (2006). Publication bias: The Achilles’ heel of systematic reviews? British Journal of Educational Studies, 54(1), 89-102.

Turnbull, B. J., Haslam, M.B., Arcaira, E.R., Riley, D.L., Sinclair, B., Coleman, S. (2009). Evaluation of the school administration manager project. Washington, DC: Policy Studies Associates.

University of California, San Francisco. (2013). Conflict of interest in research. https://coi.ucsf.edu

U.S. Department of Education. (2019). Data point: Adult literacy in the United States.https://nces.ed.gov/datapoints/2019179.asp

U.S. Department of Education. (2020). National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/

Villar, A., Strong, M., & Fletcher, S. (2007). The relation between years of teaching experience and student achievement: Evidence from five years of value-added English and Mathematics data from one school district.Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

Walberg, H. J. (1999). Productive teaching. In H. C. Waxman & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), New directions for teaching practice and research (pp. 75–104). Berkeley, CA: McCutchan Publications.

Walsh, K., Glaser, D., & Dunne Wilcox, D. (2006). What education schools aren’t teaching about reading and what elementary teachers aren’t learning. New York, NY: National Council on Teacher Quality.

Wenglinsky, H. (2002). The link between teacher classroom practices and student academic performance. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 10(12), 1–30.

Yeh, S. S., (2007). The cost-effectiveness of five policies for improving student achievement. American Journal of Evaluation, 28(4), 416–436.