Teacher Retention and Turnover

Teacher Retention and Turnover Dashboard PDF

Donley, J. & States, J. (2019). Teacher Retention and Turnover Dash Board. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/staff-retention-turnover.

As research has reliably demonstrated, classroom teachers exert the strongest influence on the educational outcomes of students (Coleman et al., 1966; Hanushek & Rivken, 2006); these include both short- and long-term academic outcomes (Chetty, Freidman, & Rockoff, 2014; Lee, 2018) as well as noncognitive outcomes such as motivation and self-efficacy (Jackson, 2018). Teachers become more effective as they accumulate years of teaching experience (Kini & Podolsky, 2016); when teachers leave a school, they take along their knowledge and expertise in instructional strategies, collaborative relationships with colleagues, professional development training, and understanding of students’ learning needs at the school, all of which harm student learning and school operations and climate (Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010; Ingersoll, 2001; Ronfeldt, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2013; Simon & Johnson, 2015). (For a complete analysis see Teacher Turnover Analysis Overview and Retention Strategies)

Summary and Conclusions

Teacher turnover has been a persistent challenge; while the national rate has hovered at 16% in recent decades, more teachers are leaving the profession, contributing to teacher shortages in hard-to-staff subjects and schools. The failure to retain teachers has a generally negative impact on students and schools. Problems with teacher turnover contribute significantly to teacher shortages and result in the inequitable distribution of effective and qualified teachers across schools. Economically disadvantaged schools suffer high levels of turnover and are forced to hire larger numbers of alternatively certified teachers, who are more likely to turn over. While value-added research suggests that less effective teachers are more likely to depart schools (thus benefiting workforce quality), other research using teacher licensure scores as a proxy for teacher quality suggests that more effective teachers with more experience are more likely to turn over (thus lowering workforce quality).

Teacher turnover is also detrimental to student achievement and the adverse consequences may extend even to students of teachers who remain in schools. The impact of turnover may also include disruptions to school operations and teacher collegiality, the loss of institutional knowledge, and reluctance by teachers to engage in teacher leadership activities, all of which can serve as barriers to school improvement. Further, turnover is quite costly in terms of separation and hiring costs, as well as losses to educational productivity when schools lose more experienced teachers to less experienced ones.

Turnover can be positive when it improves the quality of the teacher workforce. Strategic retention of effective teachers combined with the departure of ineffective teachers, has the potential to maximize the benefits of turnover and improve workforce quality. However, hard-to-staff schools may also require incentives to both retain their best teachers and attract effective candidates to fill the slots vacated by less effective teachers.

Mover and Leavers

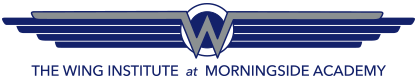

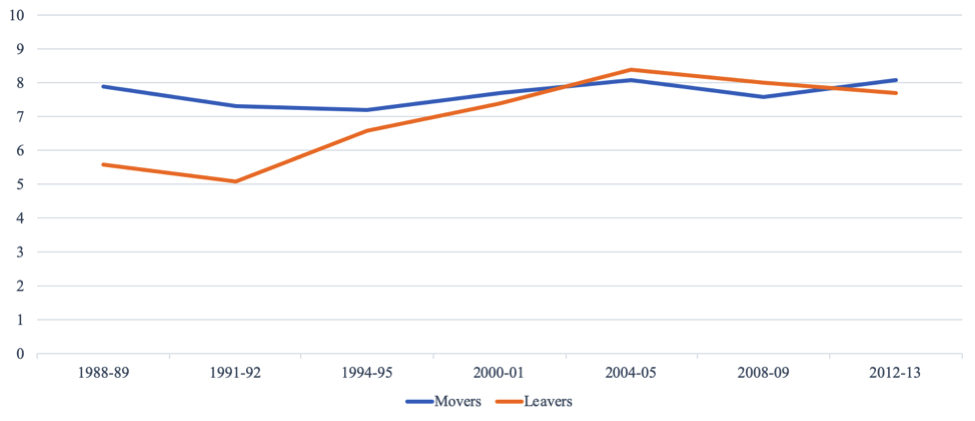

Figure 1. Percentage of public school teacher movers and leavers, 1988–1989 through 2012–2013

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics report “Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey” (Goldring, Taie, & Riddles, 2014).

Reasons Why Teachers Leave

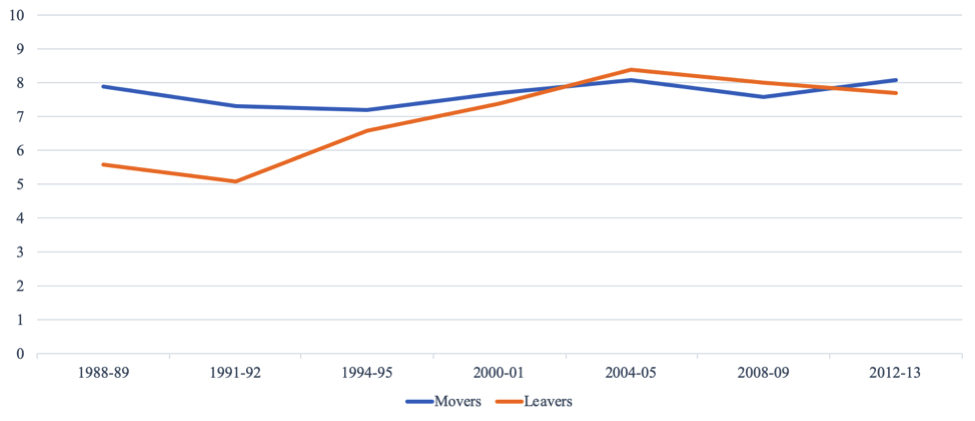

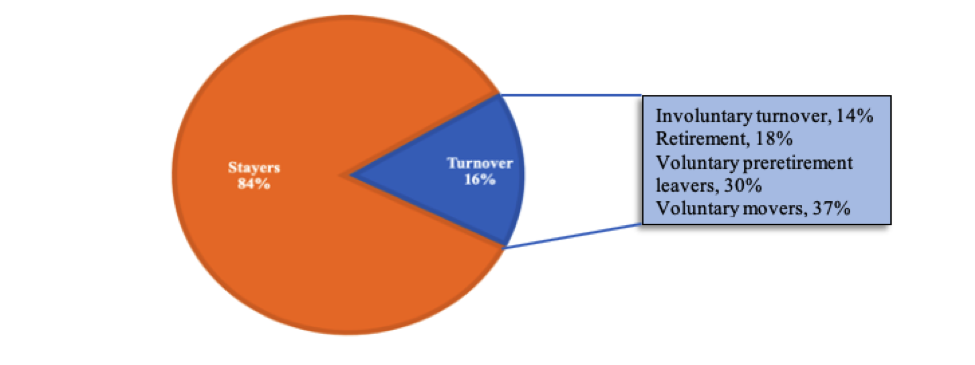

Figure 2. Sources of teacher turnover, 2011–2012 to 2012–2013

Adapted from Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019). Note: percentages do not total 100 due to rounding.

While the percentage of movers has remained fairly consistent across 25 years of the study, the percentage of leavers increased substantially from 1991–1992 and peaked in 2004–2005, suggesting increasing problems with attrition during that time period. In fact, an additional analysis of the sources of turnover from 2011–2012 to 2012–2013 found that voluntary preretirement turnover (including movers and leavers) represented two thirds of the turnover rate during these years (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019), as shown in Figure 2.

Types of Schools Where Teachers Move

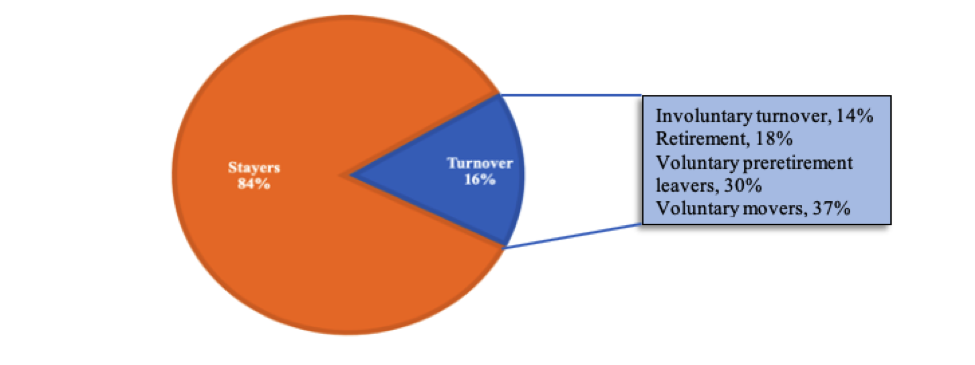

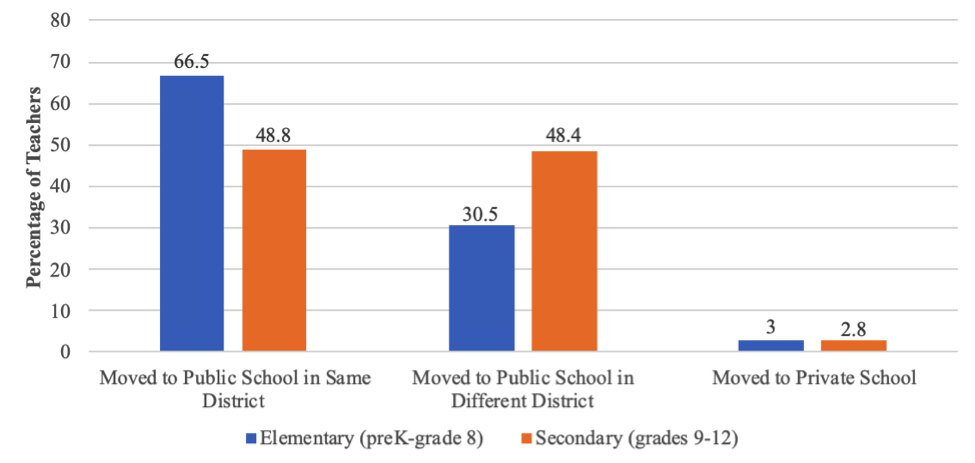

Figure 3. Percentage of public school teachers who moved to a different school by school level and destination, 2011–2012 to 2012–2013

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Education Digest Report (2017).

Research shows that the movement of teachers out of schools differs by school level and type of school, and is not equally distributed across states, regions, and districts (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Recent national data from 2011–2012 to 2012–2013 show that 8.9% of elementary teachers moved to a different school compared with 7.2% of secondary teachers, but secondary teachers were more likely to leave teaching (8.3%) than elementary teachers (7.1%) (U.S. Department of Education, 2017). Figure 3 depicts the destination of teachers who moved to a different school. Elementary teachers were much more likely to move within-district than outside of the district, while approximately equal rates were seen for secondary teachers. Few elementary or secondary teachers transferred to a private school. While private schools may have advantages such as better working conditions (e.g., smaller class sizes) (Orlin, 2013), they may be less likely to attract public school teachers due to lower salaries and lack of compensation for years of service in teacher retirement systems.

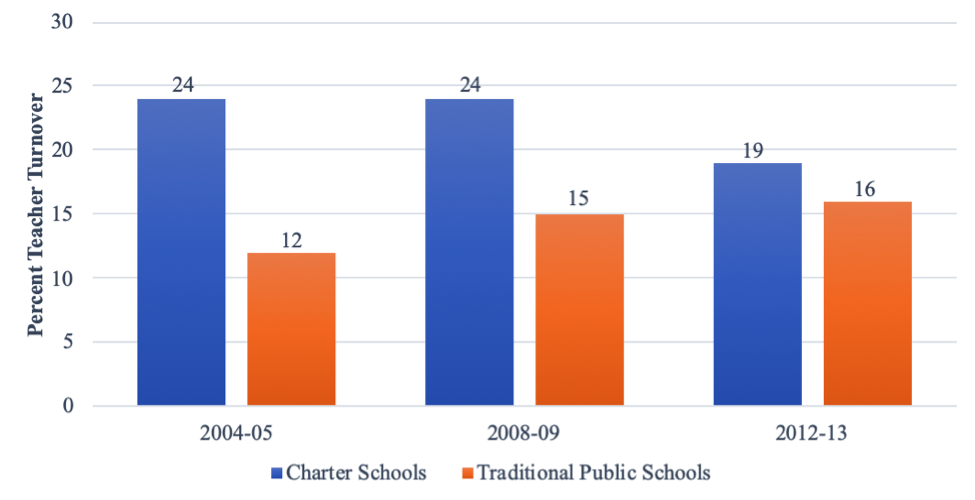

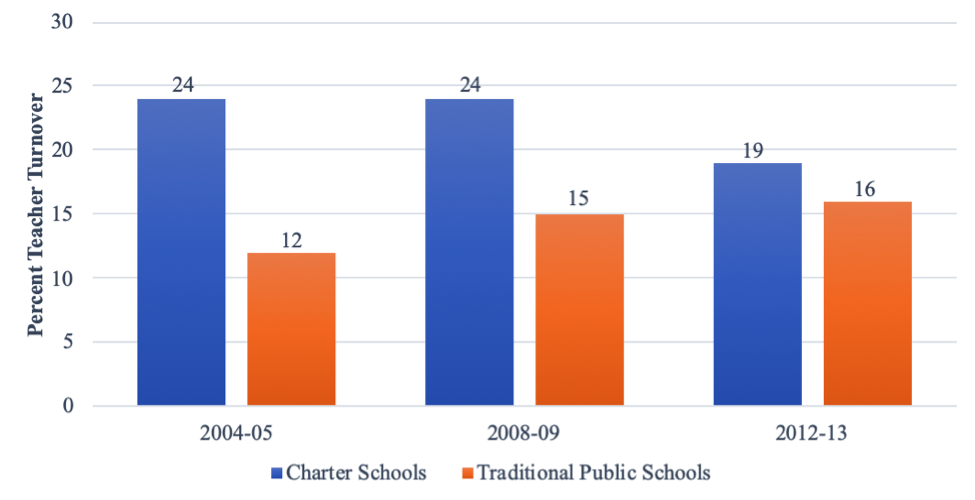

Figure 4. Turnover rates at charter schools and traditional public schools, 2004–2005 to 2012–2013

Adapted from Goldring et al., 2014; Stuit and Smith (2012).

While these trends are encouraging, there is a great degree of variability in turnover in charter schools across various regions and states. For example, Newton and colleagues (2018) found significantly higher turnover rates in Los Angeles charter schools than in traditional public schools, even when controlling for student, teacher, and school characteristics. Specifically, elementary charter school teachers had approximately 35% higher odds of leaving and secondary charter school teachers were close to 4 times more likely to exit their schools than their counterparts in traditional public schools. Naslund and Ponomariov (2019) found that Texas charter school teachers turn over at twice the rate as traditional public school teachers (36.7% versus 18.2%).

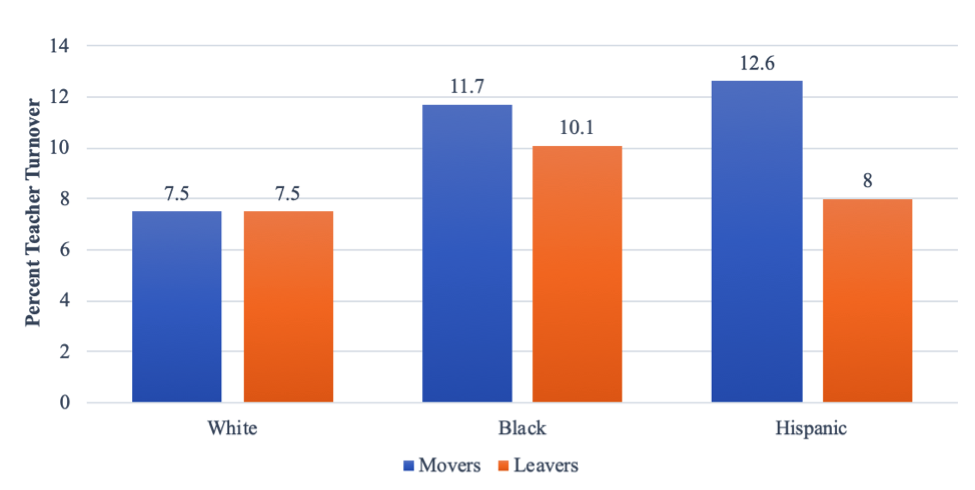

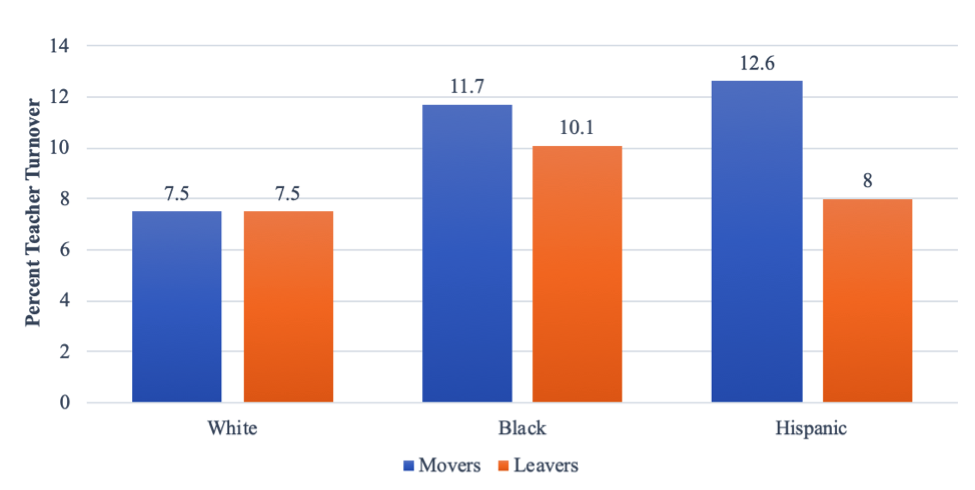

Figure 5. Percentage of public school teacher movers and leavers by teacher ethnicity, 2012–2013

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics report “Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey” (Goldring, Taie, & Riddles, 2014). Data are not included for teachers of other ethnicities due to reporting standards not being met because of unacceptably high standard errors.

Studies by Ingersoll and colleagues (2017) and Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019) also found larger gaps between teachers of color and White teacher movers than leavers, and the data in both studies suggested that the difficult working conditions in many hard-to-staff schools were responsible for the higher rates of minority teacher turnover. Minority teacher turnover in these schools may be particularly problematic given research that suggests positive academic and behavioral benefits for minority students assigned to teachers of the same ethnicity (Redding, 2019).

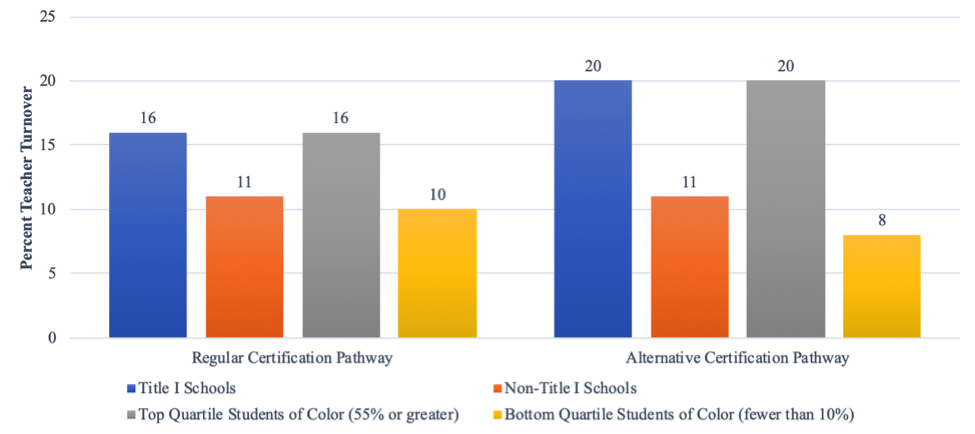

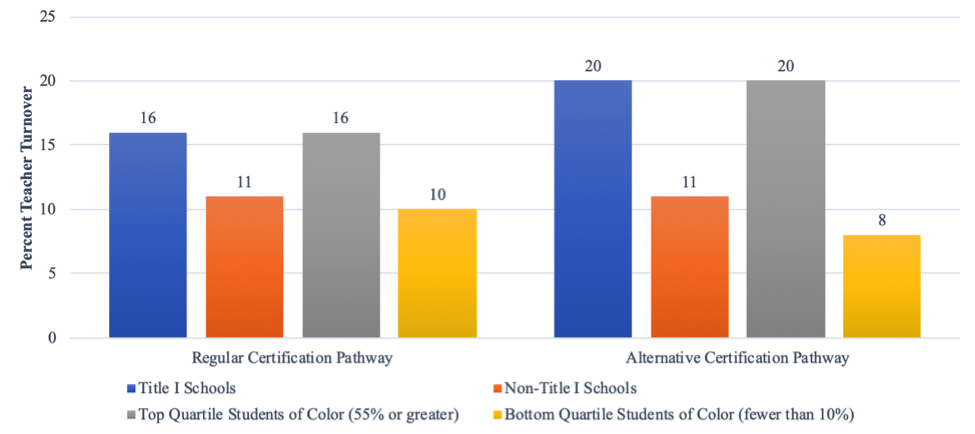

Figure 6. Teacher turnover by type of school and teacher certification, 2011–2012 to 2012–2013

Adapted from Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2019)

Alternatively certified teachers are more likely to work in urban schools in disadvantaged communities, where working conditions are often less than optimal (Cohen-Vogle & Smith, 2007), with less preparation and support than for traditionally certified teachers (Redding & Smith, 2016). Combining teaching and coursework for certification likely is overwhelming and contributes to the difficult professional situation for these teachers (Redding & Henry, 2019).

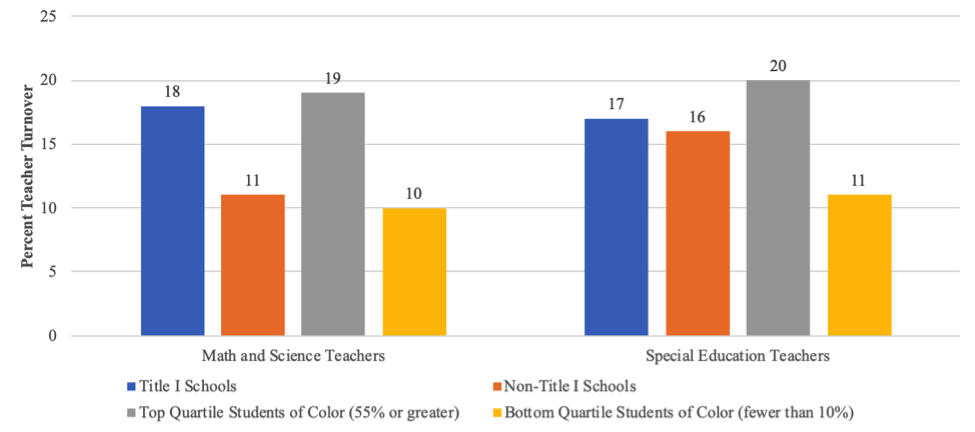

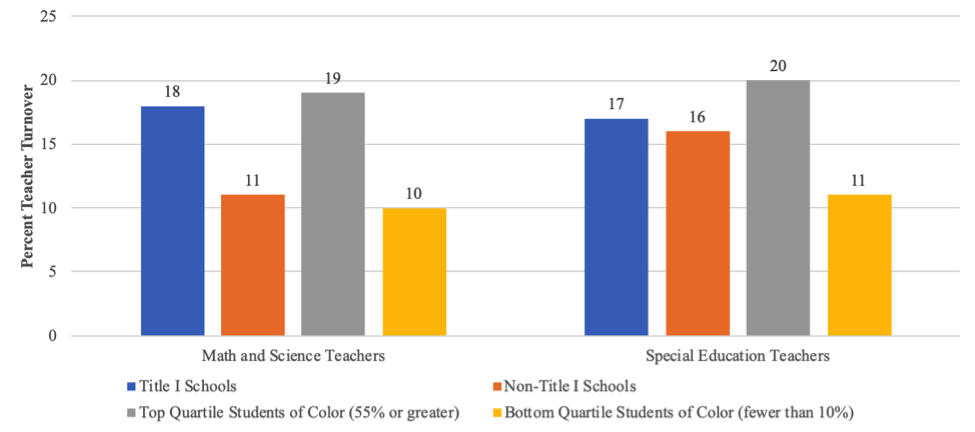

Figure 7. Turnover for math/science and special education teachers, 2011–2012 to 2012–2013

Adapted from Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond, (2019)

Figure 7 shows that while no significant difference in turnover has been found for special education teachers in Title I versus non-Title I schools, rates are considerably higher in high-minority compared with low-minority schools (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2019). Special education teachers overall have higher average turnover rates than general education teachers, particularly during the early career years (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017; Vittek, 2015). These teachers are likely to face difficult working conditions, such as excessive paperwork, lack of collaboration with colleagues, lack of appropriate induction/mentoring, and lack of administrative support, all of which increase the likelihood that they will transfer to a general education position or leave teaching entirely (Boe, Cook, & Sunderland, 2008; McLesky, Tyler, & Flippin, 2004; Vittek, 2015).

Teacher-Reported Reasons for Turnover

Understanding the reasons teachers leave may help educators develop solutions to address teacher concerns and reduce turnover.

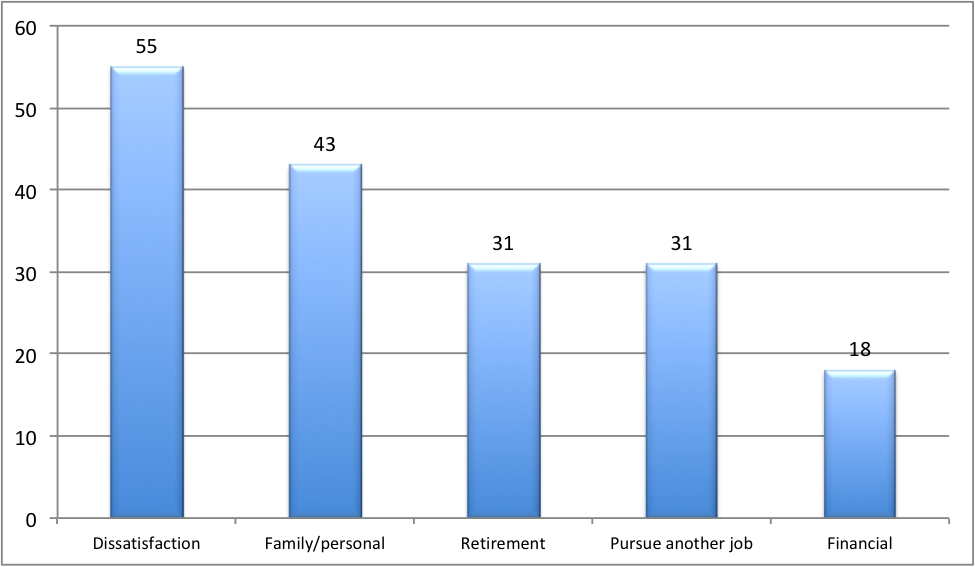

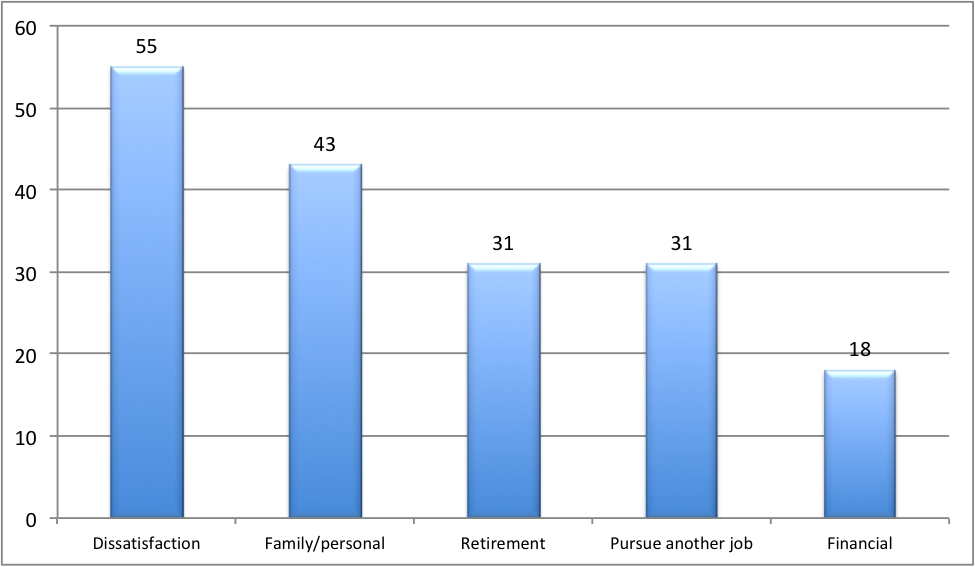

Figure 8. Factors important in teachers leaving the profession

Adapted from Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond (2017). Figure displays percentages of teachers reporting each factor as important; teachers were able to select more than one reason, so percentages do not total 100.

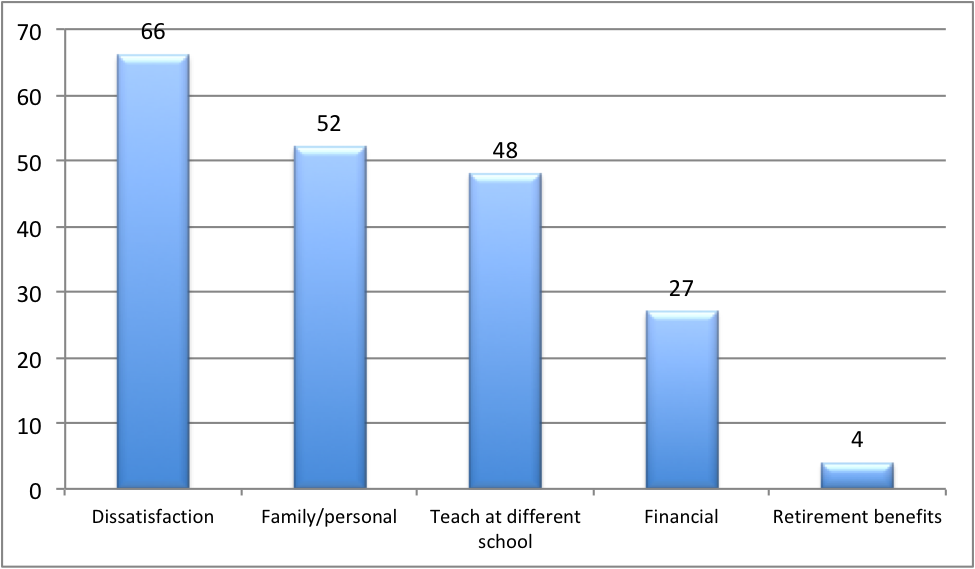

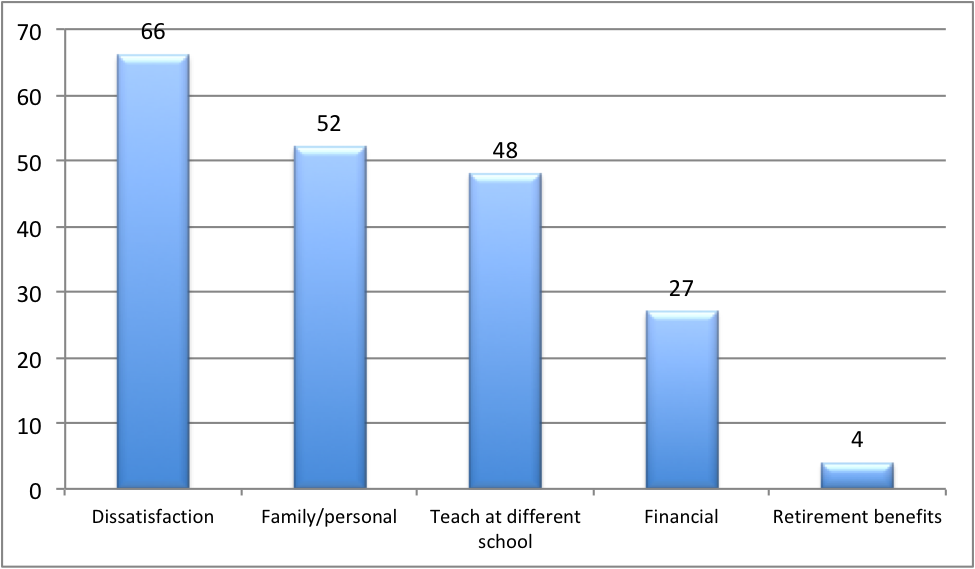

Figure 9. Factors important in teachers moving to another school

Adapted from Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond (2017). Figure displays percentages of teachers reporting each factor as important; teachers were able to select more than one reason, so percentages do not total 100.

Dissatisfaction was most frequently cited by both movers and leavers as important in their decision to leave. Leavers most frequently cited testing/accountability (25%), problems with administration (21%), and dissatisfaction with teaching as a career (21%) as sources of dissatisfaction; the family/personal reasons they cited included moving to a more conveniently located job, health reasons, and caring for family members. Two thirds of movers reported dissatisfaction as a reason to move, citing concerns with school administration, lack of influence on school decision making, and school conditions such as inadequate facilities and resources (Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond’s 2019 research also found that a perceived lack of administrative support and compensation were significantly related to turnover. These findings highlight the importance of working conditions in teacher retention.

Teacher Working Conditions

Working conditions are an important predictor of teacher turnover (e.g., Borman & Dowling, 2008; Goldring et al., 2014; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Johnson, Kraft, & Papay, 2012), and offer potentially malleable school conditions that can be shaped by changes to educational policy (Katz, 2018). Research has demonstrated that student demographics are important in teachers’ decisions to remain at their schools and that they most often leave schools containing large numbers of low-income, low-achieving, and minority students (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Clotfelter, Ladd, Vigdor, & Wheeler, 2006; Hanushek et al., 2004). However, teacher interviews have revealed that dysfunctional school contexts that make it difficult to succeed with these student populations, rather than the students themselves, are responsible for the decision to leave (Allensworth et al, 2009; Johnson & Birkeland, 2003; Johnson et al., 2012). In fact, several studies have demonstrated that teacher working conditions explain most of the relationship between student demographics and teacher turnover (Allensworth et al., 2009; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Ladd, 2011; Simon & Johnson, 2015).

Citations

Allensworth, E., Ponisciak, S., & Mazzeo, C. (2009). The schools teachers leave: Teacher mobility in Chicago Public Schools.Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. Retrieved from https://consortium.uchicago.edu/publications/schools-teachers-leave-teacher-mobility-chicago-public-schools

Borman, G. D., & Dowling, N. M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 367–409.

Bryk A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Carver-Thomas, D. & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Turnover_REPORT.pdf

Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The trouble with teacher turnover: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(36), 1–32.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., & Rockoff, J. E. (2014). Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. American Economic Review, 104(9), 2633–2679.

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J., & Wheeler, J. (2006). High-poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. North Carolina Law Review, 85, 1345–1379.

Cohen-Vogel, L., Smith, T. M. (2007). Qualifications and assignments of alternatively certified teachers: Testing core assumptions. American Educational Research Journal, 44(3), 732–753.

Goldring, R., Taie, S., & Riddles, M. (2014). Teacher attrition and mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-up Survey (NCES 2014-077). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014077.pdf

Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., & York, R. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/ fulltext/ED012275.pdf

Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J., & Rivkin, S. (2004). Why public schools lose teachers. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 326–354.

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2006). Teacher quality. In E. A. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education, vol. 2 (pp. 1051–1078). Amsterdam, Netherlands: North Holland.

Ingersoll, R. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499–534.

Ingersoll, R., & Merrill, E. (2017). A quarter century of changes in the elementary and secondary teaching force: From 1987 to 2012 (NCES 2017-092). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., & Collins, G. (2018). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force—updated October 2018. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=cpre_researchreports

Jackson, C. K. (2018). What do test scores miss? The importance of teacher effects on non-test score outcomes. Journal of Political Economy, 126(5), 2072–2107.

Johnson, S. M., & Birkeland, S. E. (2003). Pursuing a “sense of success”: New teachers explain their career decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 581–617.

Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record, 114(10), p. 1–39.

Katz, V. (2018). Teacher retention: Evidence to inform policy. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia. Retrieved from https://curry.virginia.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/epw/Teacher%20Retention%20Policy%20Brief.pdf

Kini, T., & Podolsky, A. (2016). Does teaching experience increase teacher effectiveness? A review of the research. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teaching_Experience_Report_June_2016.pdf

Ladd, H. F. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions: How predictive of planned and actual teacher movement? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2), 235–261.

Lee, S. W. (2018). Pulling back the curtain: Revealing the cumulative importance of high-performing, highly qualified teachers on students’ educational outcome. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(3), 359–381.

McLeskey, J., Tyler, N. C., & Flippin, S. S. (2004). The supply of and demand for special education teachers: A review of research regarding the chronic shortage of special education teachers. Journal of Special Education, 38(1), 5–21.

Naslund, K., & Ponomariov, B. (2019). Do charter schools alleviate the negative effect of teacher turnover? Management in Education, 33(1), 11–20.

Newton, X., Rivero, R., Fuller, B., & Dauter, L. (2018). Teacher turnover in organizational context: Staffing stability in Los Angeles charter, magnet, and regular public schools. Teachers College Record, 120(3), 1–36.

Orlin, B. (2013, October 24). Why are private-school teachers paid less than public-school teachers? The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2013/10/why-are-private-school-teachers-paid-less-than-public-school-teachers/280829/

Redding, C., & Henry, G. T. (2019). Leaving school early: An examination of novice teachers’ within- and end-of-year turnover. American Educational Research Journal, 56(1), 204–236.

Redding, C., & Smith, T. M. (2016). Easy in, easy out: Are alternatively certified teachers turning over at increased rates? American Educational Research Journal, 53(4), 1086–1125.

Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36.

Simon, N. S., & Johnson, S. M. (2015). Teacher turnover in high-poverty schools: What we know and can do. Teachers College Record, 117(3), 1–36.

Stuit, D.A, & Smith, T.M. (2012). Explaining the gap in charter and traditional public school teacher turnover rates. Economics of Education Review, 31(2), 268–279.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Digest of Education Statistics.Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_210.30.asp

Vittek, J. E. (2015). Promoting special educator teacher retention: A critical review of the literature. SAGE Open, (5)2, 1–6.

TITLE

SYNOPSIS

CITATION

LINK

The Unavoidable: Tomorrow’s Teacher Compensation.

This research examines the issue of teacher compensation. The author finds that teachers earn significantly less than they could make working in other comparable fields.

Hanushek, E. A. (2020). The Unavoidable: Tomorrow’s Teacher Compensation. Stanford Hoover Education Success Initiative.

Teacher Induction Programs: Trends and Opportunities

State-level policy support for teacher induction programs can help teachers realize their full potential, keep them in the profession, promote greater student learning, and save money. Higher education institutions and school districts must work together to provide high-quality and well-designed induction programs.

American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU). (2006). Teacher induction programs: Trends and opportunities. Policy Matters, 3(10), 1–4.

Fears of a mass exodus of retiring teachers during COVID-19 may have been overblown

One-third of teachers told Education Week in July they were somewhat or very likely to leave their job this year, compared with just 8% who leave the profession in a typical year. But while that survey might reflect teachers' feelings over the summer, a review of the retirement and staffing figures collected in some of the first states to resume classes this year suggests that fears of a mass exodus of retiring teachers may have been overblown.

Aspegren, E. (2020, October 8). Fears of a mass exodus of retiring teachers during COVID-19 may have been overblown. USA Today.

What Do Surveys of Program Completers Tell Us About Teacher Preparation Quality?

This study uses statewide completer survey data from North Carolina to assess whether perceptions of preparation quality and opportunities to learn during teacher preparation predict completers’ value-added estimates, evaluation ratings, and retention.

Bastian, K. C., Sun, M., & Lynn, H. (2018). What do surveys of program completers tell us about teacher preparation quality? Journal of Teacher Education, November 2019.

Teacher turnover: Examining exit attrition, teaching area transfer, and school migration

The purposes of this research were to quantify trends in three components of teacher turnover and to investigate claims of excessive teacher turnover as the predominant source of teacher shortages.

Boe, E. E., Cook, L. H., & Sunderland, R. J. (2008). Teacher turnover: Examining exit attrition, teaching area transfer, and school migration. Exceptional children, 75(1), 7-31.

Evaluation of the Teacher Incentive Fund: Implementation and impacts of pay-for-performance after two years

Recent efforts to attract and retain effective educators and to improve teacher practices have focused on reforming evaluation and compensation systems for teachers and principals. In 2006, Congress established the Teacher Incentive Fund (TIF), which provides grants.

Chiang, H., Wellington, A., Hallgren, K., Speroni, C., Herrmann, M., Glazerman, S., & Constantine, J. (2015). Evaluation of the Teacher Incentive Fund: Implementation and Impacts of Pay-for-Performance after Two Years. NCEE 2015-4020. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

School Climate and Social–Emotional Learning:

Predicting Teacher Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Teaching Efficacy

The aims of this study were to investigate whether and how teachers' perceptions of social–emotional learning and climate in their schools influenced three outcome variables—teachers' sense of stress, teaching efficacy, and job satisfaction—and to examine the interrelationships among the three outcome variables.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of educational psychology, 104(4), 1189.

School Climate and Social–Emotional Learning: Predicting Teacher Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Teaching Efficacy

The aims of this study were to investigate whether and how teachers' perceptions of social–emotional learning and climate in their schools influenced three outcome variables—teachers' sense of stress, teaching efficacy, and job satisfaction—and to examine the interrelationships among the three outcome variables.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of educational psychology, 104(4), 1189.

K-12 teacher recruitment and retention policies in the Higher Education Act: In brief

One of the more difficult issues involves a debate between observers who are concerned about an overall teacher shortage, and others who see it largely as a distributional problem where some schools have a relative surplus of teachers while other schools struggle with a persistent, unmet demand for qualified teachers.

Congressional Research Service. (2019, September 4). K-12 teacher recruitment and retention policies in the Higher Education Act: In brief.

Student teaching and teacher attrition in special education

Research suggests that substantial pre-service student teaching is essential for the preparation and retention of special educators. It was found that substantial pre-service student teaching experience has a strong effect on the probability that a beginning special educator will remain in the field 1 year later.

Connelly, V., & Graham, S. (2009). Student teaching and teacher attrition in special education. Teacher Education and Special Education, 32(3), 257-269.

Missing elements in the discussion of teacher shortages

Though policymakers are increasingly concerned about teacher shortages in U.S. public schools, the national discussion does not reflect historical patterns of the supply of and demand for newly minted teachers.

Cowan, J., Goldhaber, D., Hayes, K., & Theobald, R. (2016). Missing elements in the discussion of teacher shortages. Educational Researcher, 45(8), 460–462.

Recruiting and retaining teachers: Turning around the race to the bottom in high-need schools

What is it that keeps some people in teaching and chases others out? What can be done to increase the power of the teaching profession to recruit and retain effective teachers and to create a stable, expert teaching force in all kinds of districts?

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Recruiting and retaining teachers: Turning around the race to the bottom in high-need schools. Journal of curriculum and instruction, 4(1), 16-32.

Recruiting and retaining teachers: Turning around the race to the bottom in high-need schools

What is it that keeps some people in teaching and chases others out? What can be done to increase the power of the teaching profession to recruit and retain effective teachers and to create a stable, expert teaching force in all kinds of districts?

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Recruiting and retaining teachers: Turning around the race to the bottom in high-need schools. Journal of curriculum and instruction, 4(1), 16-32.

Understanding and addressing teacher shortages in the United States.

While anecdotal accounts of substantial teacher shortages are increasingly common, we present evidence that such shortages are not a general phenomenon but rather are highly concentrated by subject and in schools where hiring and retaining teachers are chronic problems. We discuss several promising, complementary approaches for addressing teacher shortages.

Dee, T. S., & Goldhaber, D. (2017). Understanding and addressing teacher shortages in the United States. The Hamilton Project.

The cost of teacher turnover in Alaska

The costs associated with teacher turnover in Alaska are considerable, but have never been systematically calculated,1 and this study emerged from interests among Alaska education researchers, policymakers, and stakeholders to better understand these costs.

DeFeo, D. J., Tran, T., Hirshberg, D., Cope, D., & Cravez, P. (2017). The cost of teacher turnover in Alaska. Anchorage, AK: Center for Alaska Education Policy Research, University of Alaska Anchorage. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.alaska.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11122/7815/2017-CostTeacher.pdf?sequence=1

The price of misassignment: The role of teaching assignments in Teach for America teachers’ exit from low-income schools and the teaching profession.

This study is the first to examine these teachers’ retention nationwide, asking whether, when, and why they voluntarily transfer from their low-income placement schools or leave teaching altogether.

Donaldson, M. L., & Johnson, S. M. (2010). The price of misassignment: The role of teaching assignments in Teach for America teachers’ exit from low-income schools and the teaching profession. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(2), 299-323.

Teacher Retention Analysis

This report analyzes the retention problem in the United States through documentation of recent teacher turnover data, and reviews the research on the factors that contribute to teachers’ decisions to remain in the

classroom.

Donley, J. (2019). Teacher Retention Analysis. Oakland, CA: Wing Institute. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1V1YeiC6nzDooV0A1UIRQKt6dnOBMXICz/view?usp=sharing

Teacher Retention Overview

This paper examines the impact of teacher turnover on education systems. Teacher turnover is quite costly, and primarily has negative consequences for school operations, staff collegiality, and student learning.

Principal Retention Overview.

This report documents broadly the research that addresses the prevalence of principal turnover, the factors associated with a principal’s decision to leave, the consequences of principal turnover for teaching and learning, and evidence-based strategies for improving principal retention.

Donley, J., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, (2020). Principal Retention Overview. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/quality-leadership-principal-retention.

Teacher Retention Strategies

Research on teacher turnover has led to the identification of retention strategies to help advance the profession and improve the recruitment, preparation, and support of teachers. This report summarizes available research on these strategies and discusses potential barriers and research on their relative cost-effectiveness.

Donley, J., Detrich, R., States, J., & Keyworth, R. (2019). Teacher Retention Analysis Overview. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute. https://www.winginstitute.org/teacher-retention-strategies

A call to teaching

"But I am addressing my remarks not just to those of you assembled today in this majestic Rotunda but to a generation of college students, professionals rethinking their careers, military veterans, retirees and others who may be thinking of becoming a teacher. Put plain and simple, this country needs an army of great, new teachers—and I can think of no better place to start recruiting them then in Thomas Jefferson's hallowed halls."

Duncan, A. (2009). A call to teaching. Secretary Arne Duncan’s remarks at the Rotunda at the University of Virginia. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

The impact of incentives to recruit and retain teachers in “hard-to-staff” subjects: An analysis of the Florida Critical Teacher Shortage Program

We investigated the effects of a statewide program designed to increase the supply of

teachers in “hard-to-staff” areas.

Feng, L., & Sass, T. R. (2015). The Impact of Incentives to Recruit and Retain Teachers in" Hard-to-Staff" Subjects: An Analysis of the Florida Critical Teacher Shortage Program. Working Paper 141. National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER).

An investigation of the effects of variations in mentor-based induction on the performance of students in California

Policy makers are concerned about reports of teacher shortages and the high rate of attrition among new teachers. Prior studies indicate that mentor-based induction can reduce the numbers of new teachers leaving schools or the profession

Fletcher, S., Strong, M., & Villar, A. (2008). An investigation of the effects of variations in mentor-based induction on the performance of students in California. Teachers college record, 110(10), 2271-2289.

Planning for the Future: Leadership development and succession planning in education

This article reviews the research and best practices on succession planning in education as well as in other sectors. The authors illustrate how forward-thinking superintendents can partner with universities and other organizations to address the leadership challenges they face by creating strategic, long-term, leadership growth plans that build leadership capacity and potentially yield significant returns in improved student outcomes.

Fusarelli, B. C., Fusarelli, L. D., & Riddick, F. (2018). Planning for the future: Leadership development and succession planning in education. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 13(3), 286–313.

A policy agenda to address the teacher shortage in U.S. public schools

The teacher shortage in the nation's public schools—particularly in our high-poverty schools—

is a crisis for the teaching profession and a serious problem for the entire education system.

It harms students and teachers and contributes to the opportunity and achievement gaps

between students in high-poverty schools and their more affluent peers.

GarcĆa, E., & Weiss, E. (2020). A Policy Agenda to Address the Teacher Shortage in US Public Schools: The Sixth and Final Report in the'Perfect Storm in the Teacher Labor Market'Series. Economic Policy Institute.

A 50-state scan of Grow Your Own teacher policies and programs

Our scan reveals GYO to be a widespread strategy that has been leveraged in myriad ways in an attempt to solve teacher shortages and increase the racial and linguistic diversity of the educator workforce. While much variation exists in program design and delivery, states and districts are unified in the reason for promoting and investing in GYO: the belief that recruiting and preparing teachers from the local community will increase retention and equip schools with well-prepared teachers who are knowledgeable about the needs of students and families in the community.

Garcia, A. (2021). A 50-state scan of Grow Your Own teacher policies and programs. New America.

The association between teaching students with disabilities and teacher turnover.

The authors fit multilevel logistic regression models to a large state administrative dataset in order to examine (1) if the percentage of SWDs a teacher instructs was associated with turnover, (2) if this association varied by student disability, and (3) how these associations were moderated by special education certification.

Gilmour, A. F., & Wehby, J. H. (2019). The Association Between Teaching Students with Disabilities and Teacher Turnover.

Impacts of comprehensive teacher induction: Final results from a randomized controlled study

To evaluate the impact of comprehensive teacher induction relative to the usual induction support, the authors conducted a randomized experiment in a set of districts that were not already implementing comprehensive induction.

Glazerman, S., Isenberg, E., Dolfin, S., Bleeker, M., Johnson, A., Grider, M., & Jacobus, M. (2010). Impacts of Comprehensive Teacher Induction: Final Results from a Randomized Controlled Study. NCEE 2010-4027. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

The mystery of good teaching

Who should be recruited to fill the two to three million K–12 teaching positions projected to come open during the next decade? What kinds of knowledge and training should these new recruits have? These are the questions confronting policymakers as a generation of teachers retires at the same time that the so-called baby boom echo is making its way through the education system.

Goldhaber, D. (2002). The mystery of good teaching. Education next, 2(1), 50-55.

Knocking on the door to the teaching profession? Modeling the entry of prospective teachers into the workforce

We use a unique longitudinal sample of student teachers (“interns”) from six Washington state teacher training institutions to investigate patterns of entry into the teaching workforce. We estimate split population models that simultaneously estimate the impact of individual characteristics and student teaching experiences on the timing and probability of initial hiring as a public school teacher.

Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., & Theobald, R. (2014). Knocking on the door to the teaching profession? Modeling the entry of prospective teachers into the workforce. Economics of Education Review, 43, 106-124.

Public school teacher attrition and mobility in the first five years: Results from the first through fifth waves of the 2007-08 beginning teacher longitudinal study

This report provides nationally representative data on attrition and mobility of beginning teachers in public elementary and secondary schools.

Gray, L., & Taie, S. (2015). Public School Teacher Attrition and Mobility in the First Five Years: Results from the First through Fifth Waves of the 2007-08 Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study. First Look. NCES 2015-337. National center for education statistics.

The impact of the COVID-19 recession on teaching positions

Recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers is essential for student learning. As a 2019 Learning Policy Institute analysis found, “Investments in instruction, especially high-quality teachers, appear to leverage the largest marginal gains in [student] performance.” Research has shown that teacher cuts during the last recession disproportionately impacted districts and schools serving students of color and students from low-income families.

Griffith, M. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 recession on teaching positions. Learning Policy Institute.

Can good principals keep teachers in disadvantaged schools? Linking principal effectiveness to teacher satisfaction and turnover in hard-to-staff environments.

This study hypothesizes that school working conditions help explain both teacher satisfaction and turnover. In particular, it focuses on the role of effective principals in retaining teachers, particularly in disadvantaged schools with the greatest staffing challenges.

Grissom, J. A. (2011). Can good principals keep teachers in disadvantaged schools? Linking principal effectiveness to teacher satisfaction and turnover in hard-to-staff environments. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2552-2585.

Teacher recruitment and retention: A review of the recent empirical literature.

This article critically reviews the recent empirical literature on teacher recruitment and retention published in the United States.

Guarino, C. M., Santibanez, L., & Daley, G. A. (2006). Teacher recruitment and retention: A review of the recent empirical literature. Review of educational research, 76(2), 173-208.

Chronic Teacher Turnover in Urban Elementary Schools

This study examines the characteristics of elementary schools that experience chronic teacher turnover and the impacts of turnover on a school’s working climate and ability to effectively function.

Guin, K. (2004). Chronic teacher turnover in urban elementary schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12(42), 1–30.

Pay, working conditions, and teacher quality.

Eric Hanushek and Steven Rivkin examine how salary and working conditions affect the quality of instruction in the classroom.

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2007). Pay, working conditions, and teacher quality. The Future of Children, 17(1), 69–86. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ795875.pdf

Career Changers in the Classroom: A National Portrait

This volume is the third report in a series on the potential, promise, experience, and needs of career changers who are teaching in America’s classrooms today. It is based on a survey of a cross-section of such individuals conducted by Hart Research Associates in 2009.

Hart Research Associates (2010). Career changers in the classroom: A national portrait. Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation.

Education reparation: an examination of Black teacher retention

The purpose of this study was to examine the workplace factors that positively and negatively impact Black K12 teacher retention. This study utilized a mixed-method approach to examine the qualitative and quantitative data.

Hollinside, M. M. (2017). Education reparation: an examination of Black teacher retention (Doctoral dissertation).

Rethinking teacher turnover: Longitudinal measures of instability in schools

In this essay, we present a typology of teacher turnover measures, including both measures used in existing teacher turnover literature as well as new measures that we have developed.

Holme, J. J., Jabbar, H., Germain, E., & Dinning, J. (2017. Rethinking teacher turnover: Longitudinal measures of instability in schools. Educational Researcher, 47(1), 62–75.

Salary incentives and teacher quality: The effect of a district-level salary increase on teacher recruitment

A salary increase in an urban school district can attract more applicants. The policy attracted applicants who would have only applied to higher-paying school districts in the absence of the salary increase. Improvements in the applicant pool can lead to an increase in the quality of new-hires.

Hough, H. J. (2012). Salary Incentives and Teacher Quality: The Effect of a Compensation Increase on Teacher Recruitment and Retention in the San Francisco Unified School District. Stanford University.

Can a district-level teacher salary incentive policy improve teacher recruitment and retention

In this policy brief Heather Hough and Susanna Loeb examine the effect of the Quality Teacher and Education Act of 2008 (QTEA) on teacher recruitment, retention, and overall teacher quality in the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD). They provide evidence that a salary increase can improve a school district’s attractiveness within their local teacher labor market and increase both the size and quality of the teacher applicant pool.

Hough, H. J., & Loeb, S. (2013). Can a District-Level Teacher Salary Incentive Policy Improve Teacher Recruitment and Retention? Policy Brief 13-4. Policy Analysis for California Education, PACE.

Out-of-field teaching, educational inequality, and the organization of schools: An exploratory analysis

Contemporary educational theory holds that one of the pivotal causes of inadequate student achievement, especially in disadvantaged schools, is the inability of schools to adequately staff classrooms with qualified teachers. Deficits in the quantity of teachers produced and in the quality of preparation prospective teachers receive have long been singled out as primary explanations for underqualified teaching.

Ingersoll, R. (2002). Out-of-field teaching, educational inequality, and the organization of schools: An exploratory analysis.

Is there really a teacher shortage?

This report summarizes a series of analyses that have investigated the possibility that there are other factors—tied to the organizational characteristics and conditions of schools—that are behind school staffing problems.

Ingersoll, R. (2003). Is there really a teacher shortage? Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

A quarter century of changes in the elementary and secondary teaching force: From 1987 to 2012

This report utilizes the nationally representative Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS) to examine changes in the elementary and secondary teaching force in the United States over the quarter century from 1987–88 to 2011–12.

Ingersoll, R. M. (2017). A Quarter Century of Changes in the Elementary and Secondary Teaching Force: From 1987 to 2012-Statistical Analysis Report.

The magnitude, destinations, and determinants of mathematics and science teacher turnover

This study examines the magnitude, destinations, and determinants of the departures of mathematics and science teachers from public schools.

Ingersoll, R. M., & May, H. (2012). The magnitude, destinations, and determinants of mathematics and science teacher turnover. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(4), 435-464.

Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force—updated October 2018

This report summarizes the results of an exploratory research project that investigated what trends and changes have, or have not, occurred in the teaching force over the past three decades.

Ingersoll, R. M., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., & Collins, G. (2018). Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force–Updated October 2018.

The impact of mentoring on teacher retention: What the research says

This review critically examines 15 empirical studies, conducted since the mid 1980s, on the effects of support, guidance, and orientation programs— collectively known as induction — for beginning teachers.

Ingersoll, R., & Kralik, J. M. (2004). The impact of mentoring on teacher retention: What the research says. GSE Publications, 127.

Minority teacher recruitment, employment, and retention: 1987 to 2013.

This brief summarizes the results from a study of the recruitment, employment, and retention of minority k-12 teachers. The study examines the extent and sources of the minority teacher shortage—the low proportion of minority teachers in comparison to the increasing numbers of minority students in the school system.

Ingersoll, R., & May, H. (2016). Minority teacher recruitment, employment and retention: 1987 to 2013. Learning Policy Institute, Stanford, CA.

What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition?

This study addresses the question: Do the kinds and amounts of pre-service education and preparation that beginning teachers receive before they start teaching have any impact on whether they leave teaching? Authors examine a wide range of measures of teachers’ subject-matter education and pedagogical preparation.

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition?.

Impacts of Comprehensive Teacher Induction: Results from the Second Year of a Randomized Controlled Study. NCEE 2009-4072.

This research evaluated the impact of structured and intensive teacher induction programs over a three-year time period, beginning when teachers first enter the teaching profession. The current report presents findings from the second year of the evaluation and a future report will present findings from the third and final year.

Isenberg, E., Glazerman, S., Bleeker, M., Johnson, A., Lugo-Gil, J., Grider, M., ... & Britton, E. (2009). Impacts of Comprehensive Teacher Induction: Results from the Second Year of a Randomized Controlled Study. NCEE 2009-4072. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

The Irreplaceables: Understanding the Real Retention Crisis in America's Urban Schools

To identify and better understand the experience of these teachers, the authors started by studying 90,000 teachers across four large, geographically diverse urban school districts

Jacob, A., Vidyarthi, E., & Carroll, K. (2012). The Irreplaceables: Understanding the Real Retention Crisis in America's Urban Schools. TNTP.

Exploring the causal impact of the McREL Balanced Leadership Program on leadership, principal efficacy, instructional climate, educator turnover, and student achievement.

This study uses a randomized design to assess the impact of the Balanced Leadership program on principal leadership, instructional climate, principal efficacy, staff turnover, and student achievement in a sample of rural northern Michigan schools.

Jacob, R., Goddard, R., Kim, M., Miller, R., & Goddard, Y. (2015). Exploring the causal impact of the McREL Balanced Leadership Program on leadership, principal efficacy, instructional climate, educator turnover, and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(3), 314–332. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1003.6694&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Who stays in teaching and why: A review of the literature on teacher retention

The Literature Review considers research that provides insight into problems of teacher shortage and turnover, offers a comprehensive explanation for why some able teachers leave the classroom prematurely, and suggests current strategies for increasing retention rates.

Johnson, S. M., Berg, J. H., & Donaldson, M. L. (2005). Who stays in teaching and why?: A review of the literature on teacher retention. Project on the Next Generation of Teachers, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement.

the authors build on this body of work by further examining how working conditions predict both teachers‘ job satisfaction and their career plans.

Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record, 114(10), 1-39.

Teacher retention: Evidence to inform policy

This policy brief summarizes the available evidence on the policy relevant factors that affect teacher turnover.

Katz, V. (2018). Teacher retention: Evidence to inform policy. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia.

Teacher attrition and mobility: Results from the 2008–09 teacher follow-up survey

The objective of TFS is to provide information about teacher mobility and attrition among elementary and secondary school teachers who teach in grades K–12 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Keigher, A. (2010). Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2008-09 Teacher Follow-Up Survey. First Look. NCES 2010-353. National Center for Education Statistics.

Teacher layoffs, teacher quality, and student achievement: Evidence from a discretionary layoff policy.

This study present some of first evidence on the implementation and subsequent effect of discretionary layoff policies, by studying the 18th largest public school district in the nation, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS).

Kraft, M. A. (2013). Teacher Layoffs, Teacher Quality and Student Achievement: The Implementation and Consequences of a Discretionary Reduction-in-Force Policy. Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness.

School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data

This study is among the first to address the empirical limitations of prior studies on organizational contexts by leveraging one of the largest survey administration efforts ever conducted in the United States outside of the decennial population census.

Kraft, M. A., Marinell, W. H., & Shen-Wei Yee, D. (2016). School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Educational Research Journal, 53(5), 1411-1449.

Teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions: How predictive of planned and actual teacher movement?

This quantitative study examines the relationship between teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions and their intended and actual departures from schools.

Ladd, H. F. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions: How predictive of planned and actual teacher movement?. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2), 235-261.

Perceived effects of scholarships on STEM majors’ commitment to teaching in high need schools

This study examines the Noyce Program, which provides scholarships for STEM majors in return for teaching in high need schools. Implications for teacher education programs include that recruitment strategies should identify candidates who are committed to teaching in high need schools and programs should provide experiences to encourage this commitment not just to become certified.

Liou, P. Y., Kirchhoff, A., & Lawrenz, F. (2010). Perceived effects of scholarships on STEM majors’ commitment to teaching in high need schools. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 21(4), 451-470.

How teaching conditions predict teacher turnover in California schools.

Using California teacher survey data linked to district data on salaries and staffing patterns, this study examines a range of school conditions as well as demographic factors and finds that high levels of school turnover are strongly affected by poor working conditions and low salaries, as well as by student characteristics.

Loeb, S., & Luczak, L. D. H. (2013). How Teaching Conditions Predict: Teacher Turnover in California Schools. In Rendering School Resources More Effective (pp. 48-99). Routledge.

Effective schools: Teacher hiring, assignment, development, and retention

In this paper, the authors use value-added methods to examine the relationship between a school’s effectiveness and the recruitment, assignment, development and retention of its teachers.

Loeb, S., Béteille, T., & Kalogrides, D. (2012). Effective schools: Teacher hiring, assignment, development, and retention. Education Finance and Policy, 7(3), 269–304.

Why teachers leave—or don’t: A look at the numbers

Deciding to leave any job can be hard, but for teachers, exiting the classroom can be downright heartbreaking. Teaching, in it's essence, is about relationships- understanding students needs, fostering their passions, figuring out what makes them tick.

Loewus, L. (2021, May 4). Why teachers leave—or don’t: A look at the numbers. Education Week

Who stays and who leaves? Findings from a three-part study of teacher turnover in NYC middle schools

This research summary focuses on aspects of the study’s results that are likely to be most useful for policymakers and school leaders as they strive to maintain and manage an effective teacher workforce.

Marinell, W. H., & Coca, V. M. (2013). " Who Stays and Who Leaves?" Findings from a Three-Part Study of Teacher Turnover in NYC Middle Schools. Online Submission.

Creating Sustainable Teacher Career Pathways: A 21st Century Imperative

The authors offer a new vision of teacher career pathways for the 21st century that holds promise for recruiting and retaining excellent teachers who further student learning. They showcase recent initiatives at the local, state, and national level that promote teacher role differentiation and create different models of teacher staffing and teacher career continuums.

Natale, C. F., Bassett, K., Gaddis, L., & McKnight, K. (2013). Creating sustainable teacher career pathways. 2013-07-05)[2016-02-19]. http://researchnetwork. pearson, com/wp-content/uploads/CSTCP-21 CI-pk-final-WEB. pdf.

The effect of a new teacher induction program on the new teachers reported teacher goals for excellence, mobility and retention rates

Over the past twenty years there has been a decline in the number of minority teachers entering and remaining in the teaching profession. While the overall teacher shortage is worrisome for educators and administrators, the shortage of minority teachers is one of grave concern. A lack of minority educators inside our buildings is just one consequence of minority teacher shortage.

Perry, B., & Hayes, K. (2011). The Effect of a New Teacher Induction Program on New Teachers Reported Teacher Goals for Excellence, Mobility, and Retention Rates. International journal of educational leadership preparation, 6(1), n1.

Review of research on the impact of beginning teacher induction on teacher quality and retention.

The objective in this review was to summarize and critique empirical research on the impact of beginning teacher induction on teacher retention and teacher quality (particularly studies in which teacher effectiveness was evaluated by using student achievement measures).

Rogers, M., Lopez, A., Lash, A., Schaffner, M., Shields, P., & Wagner, M. (2004). Review of research on the impact of beginning teacher induction on teacher quality and retention.

Where should student teachers learn to teach? Effects of field placement school characteristics on teacher retention and effectiveness

This study is motivated by an ongoing debate about the kinds of schools that make for the best field placements during pre-service preparation. On the one hand, easier-to-staff schools may support teacher learning because they are typically better-functioning institutions that offer desirable teaching conditions.

Ronfeldt, M. (2012). Where should student teachers learn to teach? Effects of field placement school characteristics on teacher retention and effectiveness. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(1), 3-26.

Field placement schools and instructional effectiveness

Student teaching has long been considered a cornerstone of teacher preparation. One dimension thought to affect student teacher learning is the kinds of schools in which these experiences occur. Results suggest that better functioning school organizations with positive work environments make desirable settings for teacher learning and that preparation programs, and the districts they supply, would benefit from more strategically using these kinds of schools to prepare future teachers.

Ronfeldt, M. (2015). Field placement schools and instructional effectiveness. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(4), 304-320.

Principal Professional Development: New Opportunities for a Renewed State Focus

This brief describes: (1) The need for more and better principal professional development to improve principal effectiveness, decrease principal turnover, and more equitably distribute successful principals across all schools; (2) The research on the importance of principals and how professional development can improve principals' effectiveness; and (3) Options and examples for leveraging current policies to revisit and refocus efforts concerning principal professional development.

Rowland, C. (2017). Principal Professional Development: New Opportunities for a Renewed State Focus. Education Policy Center at American Institutes for Research.

Teacher recruitment and retention: A critical review of international evidence of most promising interventions

A raft of initiatives and reforms have been introduced in many countries to attract and recruit school teachers, many of which do not have a clear evidence base, so their effectiveness remains unclear. Prior research has been largely correlational in design. This paper describes a rigorous and comprehensive review of international evidence, synthesizing the findings of some of the strongest empirical work so far.

See, B. H., Morris, R., Gorard, S., Kokotsaki, D., & Abdi, S. (2020). Teacher recruitment and retention: A critical review of international evidence of most promising interventions. Education Sciences, 10(10), 262.

Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion.

This study examines the relations between school context variables and teachers’ feeling of belonging, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to leave the teaching profession. Six aspects of the school context were measured: value consonance, supervisory support, relations with colleagues, relations with parents, time pressure, and discipline problems.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and teacher education, 27(6), 1029-1038.

Teacher expectations.

The purpose of this paper is to integrate statistically the results of the literature on teacher expectations.

Smith, M. L. (1980). Teacher expectations. Evaluation in Education, 4, 53-55.

A Review of the Literature on Principal Turnover.

This paper examines research on what we know about the causes and impact of principal turnover.

Snodgrass Rangel, V. (2018). A review of the literature on principal turnover. Review of Educational Research, 88(1), 87-124.

The hidden costs of teacher turnover.

High teacher turnover imposes numerous burdens on the schools and districts from which teachers depart. Some of these burdens are explicit and take the form of recruiting, hiring, and training costs. Others are more hidden and take the form of changes to the composition and quality of the teaching staff. This study focuses on the latter.

The Hidden Cost of Teacher Turnover

This study asks how schools respond to spells of high teacher turnover, and assesses organizational and human capital losses in terms of the changing composition of the teacher pool.

Sorensen, L. C., & Ladd, H. F. (2018). The hidden costs of teacher turnover. Working Paper No. 203-0918-1. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). Retrieved from https://caldercenter.org/publications/hidden-costs-teacher-turnover

Effective teacher retention bonuses: Evidence from Tennessee

We report findings from a quasi-experimental evaluation of the recently implemented US$5,000 retention bonus program for effective teachers in Tennessee’s Priority Schools. We estimate the impact of the program on teacher retention using a fuzzy regression discontinuity design by exploiting a discontinuity in the probability of treatment conditional on the composite teacher effectiveness rating that assigns bonus eligibility.

Springer, M. G., Swain, W. A., & Rodriguez, L. A. (2016). Effective teacher retention bonuses: Evidence from Tennessee. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(2), 199-221.

Teacher induction, mentoring, and retention: A summary of the research

This paper reviews the research literature on new teacher mentoring, focusing on issues of definition, why teachers quit, and the effects of mentoring on retention.

Strong, M. (2005). Teacher induction, mentoring, and retention: A summary of the research. The New Educator, 1(3), 181-198.

Teacher Quality Index

This book examines issues pertaining to making effective hiring decisions. The authors present a research-based interview protocol built on quality indicators.

Stronge, J. and Hindman, J., (2006). Teacher Quality Index. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S

Recent media reports of teacher shortages across the country are confirmed by the analysis

of several national datasets reported in this brief. Shortages are particularly severe in

special education, mathematics, science, and bilingual/English learner education, and in

locations with lower wages and poorer working conditions.

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the US. Learning Policy Institute.

Fifty years of federal teacher policy: An appraisal

The federal role in developing the teacher workforce has increased markedly in the last

decade, but the history of such involvement dates back fifty years. Relying initially on

policies to recruit and train teachers, the federal role has expanded in recent years to

include new policy initiatives and instruments around the themes of accountability,

incentives, and qualifications, while also continuing the historic emphasis on teacher

recruitment, preparation, and development.

Sykes, G., & Dibner, K. (2009). Fifty Years of Federal Teacher Policy: An Appraisal. Center on Education Policy.

The impact of newly qualified teachers (NQT) induction programmes on the enhancement of teacher expertise, professional development, job satisfaction or retention rates: A systematic review of research literature on induction

The main aim of this report is to identify and map studies that will shed light on the impact of induction programmes on teacher performance, career development and retention rates.

Totterdell, M., Bubb, S., Woodroffe, L., & Hanrahan, K. (2004). The impact of newly qualified teachers (NQT) induction programmes on the enhancement of teacher expertise, professional development, job satisfaction or retention rates: A systematic review of research literature on induction. Research evidence in education library.

Teacher recruitment and retention: It’s complicated

In certain states and districts, and in particular specialties like special education or foreign

languages, teacher shortages are a recurring fact of life. An Education Week analysis of

federal data finds that all 50 states and most territories reported experiencing statewide

shortages in one teaching area or another for either the 2016-17 school year, the current

one, or both.

Viadero, D. (2018). Teacher recruitment and retention: It’s complicated. Education Week, 37(18), 4-5.

What teachers want: School factors predicting teachers’ decisions to work in low-performing schools

Attracting and retaining teachers can be an important ingredient in improving low-performing schools. In this study, we estimate the expressed preferences for teachers who have worked in low-performing schools in Tennessee. Using adaptive conjoint analysis survey design, we examine three types of school attributes that may influence teachers’ employment decisions: fixed school characteristics, structural features of employment, and malleable school processes.

Viano, S., Pham, L. D., Henry, G. T., Kho, A., & Zimmer, R. (2021). What teachers want: School factors predicting teachers’ decisions to work in low-performing schools. American Educational Research Journal, 58(1), 201-233.

Teachers say they are more likely to leave the classroom because of coronavirus

Two-thirds of educators say they’re concerned about the health implications of resuming in-person instruction in the fall, and some say the coronavirus outbreak—and its dramatic effects on schooling—has increased the likelihood that they will leave the classroom altogether.

Will, M. (2020). Teachers say they’re more likely to leave the classroom because of coronavirus. Education Week.

Failing Teachers?

This book describes the research undertaken during the Teaching Competence Project, a two-year research project funded by the Gatsby Charitable Foundation. There were five interlinked studies in the research.

Wragg, E. C., Chamberlin, R. P., & Haynes, G. S. (2005). Failing teachers?. Routledge.