What evidence do principals rely on in assessing the quality of a teacher’s instruction?

Why is this question important? Evidence strongly indicates that, in schools, teachers are the dominant influence on student achievement (Babu & Mendro, 2003). Of all the factors associated with schools, how teachers teach has the greatest impact on achievement (Hattie, 2009). Trailing closely behind teachers in importance are principals (Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2005). Research singles out instructional leadership as key to a principal's success and suggests that a principal's greatest leverage in improving student performance is in how he or she supports teachers in developing effective teaching practices (Robinson, 2007). To apply that leverage effectively, a principal needs current and accurate information on each teacher's skill level in order to foster a teacher's continuous improvement in the use of evidence-based instructional practices (Sprick, Knight, Reinke, Skyles, & Barnes, 2010). Ensuring that school principals acquire this information is critical in maximizing their impact on teachers and ultimately on student achievement.

See further discussion below.

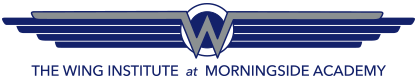

Figure 1

Figure 1

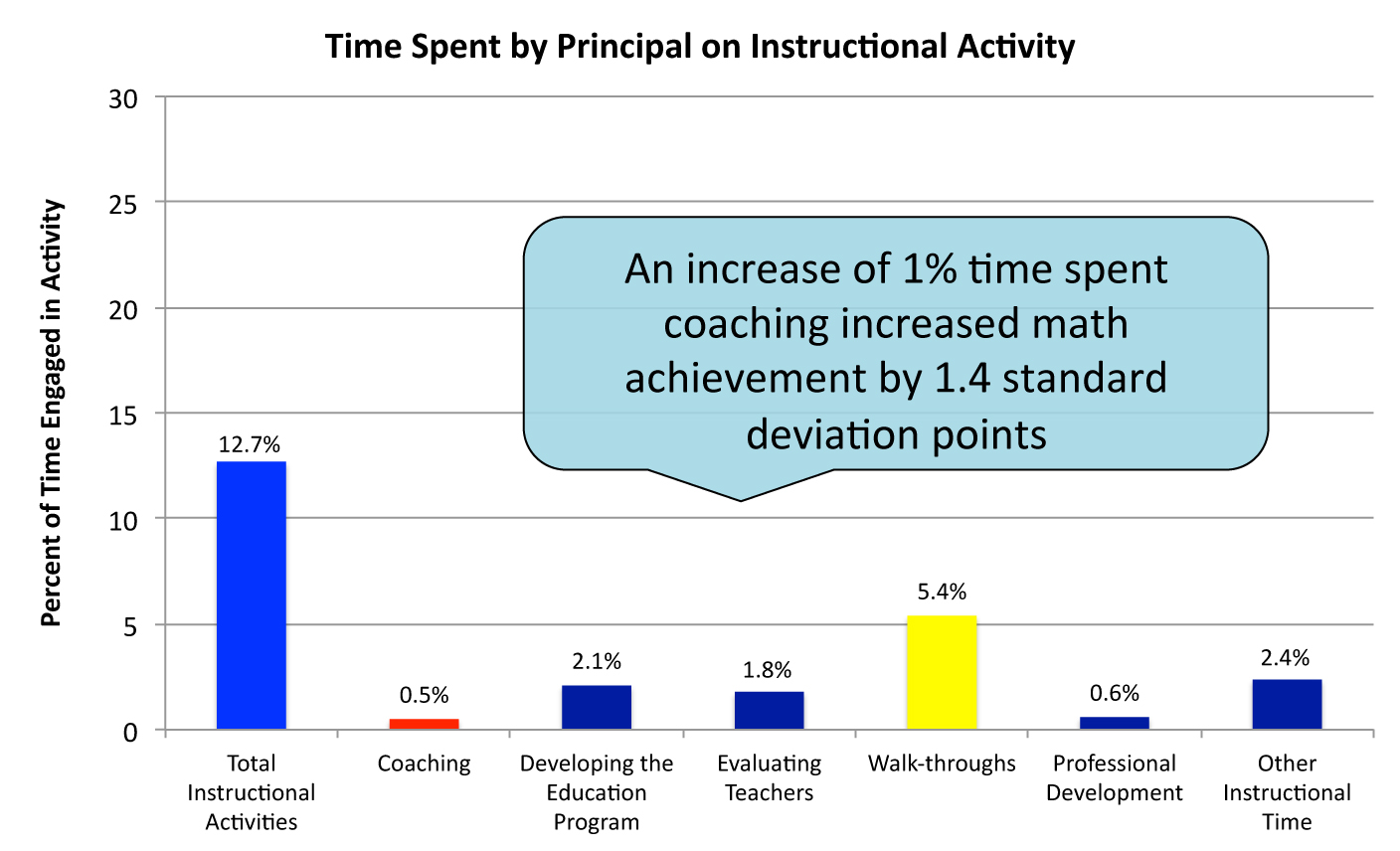

Figure 2

Figure 2

Results: The Grissom, Loeb, and Master (2013) study found that principals depend on unscheduled walk-throughs as an essential source of information on how teachers teach. Some 62% of principals reported walk-throughs as their primary source of teacher instructional practices (Fig. 1). Disappointingly, when observed, principals allocated less than 13% of their day to the topic of teacher instruction (Fig. 2). When the study examined principal leadership behaviors, it found that many of the instructional leadership activities that principals engaged in were not strongly associated with student academic gains. The study also found that the popular informal classroom walk-through had little to no positive impact on improving teacher performance. On the other hand, coaching was found to have a positive impact on student achievement. For example, an increase of 1% of the principal's time spent on coaching increased mathematics achievement by 1.4 standard deviation points. The study found that other practices such as evaluation of teachers and development of the school's educational program were also associated with positive gains. Despite their impact on student achievement, these practices were underutilized in comparison with walk-throughs.

Classroom walk-throughs accounted for 5.4% of a principal's time and were the most common practice in assessing a teacher's teaching skills. Formal evaluations accounted for 1.8% of a principal's time. Principals spent only 0.5% of their time coaching teachers, which the evidence tells us is the most effective method for improving teacher performance. Only 2.1% of a principal's time was dedicated to developing the educational program and evaluating the curriculum. Direct observations of principals revealed that time spent on professional development planning and execution varied greatly, but on average accounted for only 0.6% of time use. An additional nine instructional categories accounted for the remaining 2.4% of a principal's time.

Implications: Given the stubbornly slow pace of reform efforts to show tangible results, it is crucial that educators move away from practices that have a poor track record and begin to adopt leadership practices that are shown to be effective (National Center for Education Statistics, 2013). Recognizing the fact that evidence-based instructional practices are essential to quality education and also acknowledging that principals play a critical role in mentoring and building quality instructional practice, it follows that principals need to know how effective their teachers are in delivering instruction if they are to foster teacher learning and development. It is only once they are equipped with this fundamental knowledge that principals can contribute to significant and rapid improvements in teacher instructional competency. Research suggests moving away from walk-throughs and increasing time spent actively engaged in coaching and training teachers in best practices of instruction (Joyce & Showers, 2002; Hattie, 2009).

Study Description: The primary purpose of the study was to identify the percentage of a principal's time employed in instructional activities. The research examined five types of instructional activities: (a) coaching teachers to improve their instructional practice; (b) developing the school's educational program or evaluating the curriculum; (c) evaluating teachers through a formal process; (d) using informal classroom walk-throughs to observe practice; and (e) planning or participating in teacher professional development. The study used full-day observations of 100 urban principals collected over 3 years to obtain direct data on actual time spent on activities. To identify specific instructional activities that were more predictive of a school's achievement growth, the researchers linked their observations to a school's student and personnel data to establish which practices were more likely to produce improvement in student performance. Finally, the study used survey data to learn which sources of information principals said they relied on in making decisions about the instructional competency of their staff.

Citation:

Babu, S. & Mendro, R. (2003) Teacher accountability: HLM-based teacher effectiveness indices in the investigation of teacher effects on student achievement in a state assessment program. Presented at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) annual meeting, Chicago, IL.

* Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., & Master, B. (2013). Effective instructional time use for school leaders: Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Educational Researcher, 42(8), 433–444.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Joyce, B. R., & B. Showers (2002). Student achievement through staff development (3rd ed). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Marzano, R. J., Waters, T., & McNulty, B. A. (2005). School leadership that works: From research to results. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2013). The nation's report card. A first look: 2013 mathematics and reading. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/naepdata/report.aspx?app=NDE&p=1-RED-2-20133%2c20113%2c20093%2c20073%2c20053%2c20033%2c20023%2c20003%2c20002%2c19983%2c19982%2c19942%2c19922-RRPCM-TOTAL-NT-ALC_BB%2cALC_AB%2cALC_AP%2cALC_AD-Y_J-0-0-37.

Robinson, V. M. J. (2007). School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why (Vol. 41). Winmalee, Australia: Australian Council for Educational Leaders

Sprick, R, Knight, J., Reinke, W., Skyles, T. M., & Barnes, L. (2010). Coaching classroom management: Strategies and tools for administrators and coaches. Eugene, OR: Pacific Northwest Publishing.

* Study from which the graphs were derived.