What are the certification and licensure requirements across the United States for school principals?

Why is this question important? Increasingly, school principals are being held accountable for measurable results in student achievement (Herrington & Willis, 2005). At the same time, research links the role that principals play to improved student performance (Leithwood, Seashore Louis, Anderson, & Wahlstrom, 2004; Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008). This increased focus on the importance of the school principal has come with calls for changes in how principals are prepared and certified (Finn & Broad, 2003; Levine, 2005). The first step in making substantive changes in principal eligibility, preparation, and certification is to understand the current labyrinth of requirements across the country.

See further discussion below.

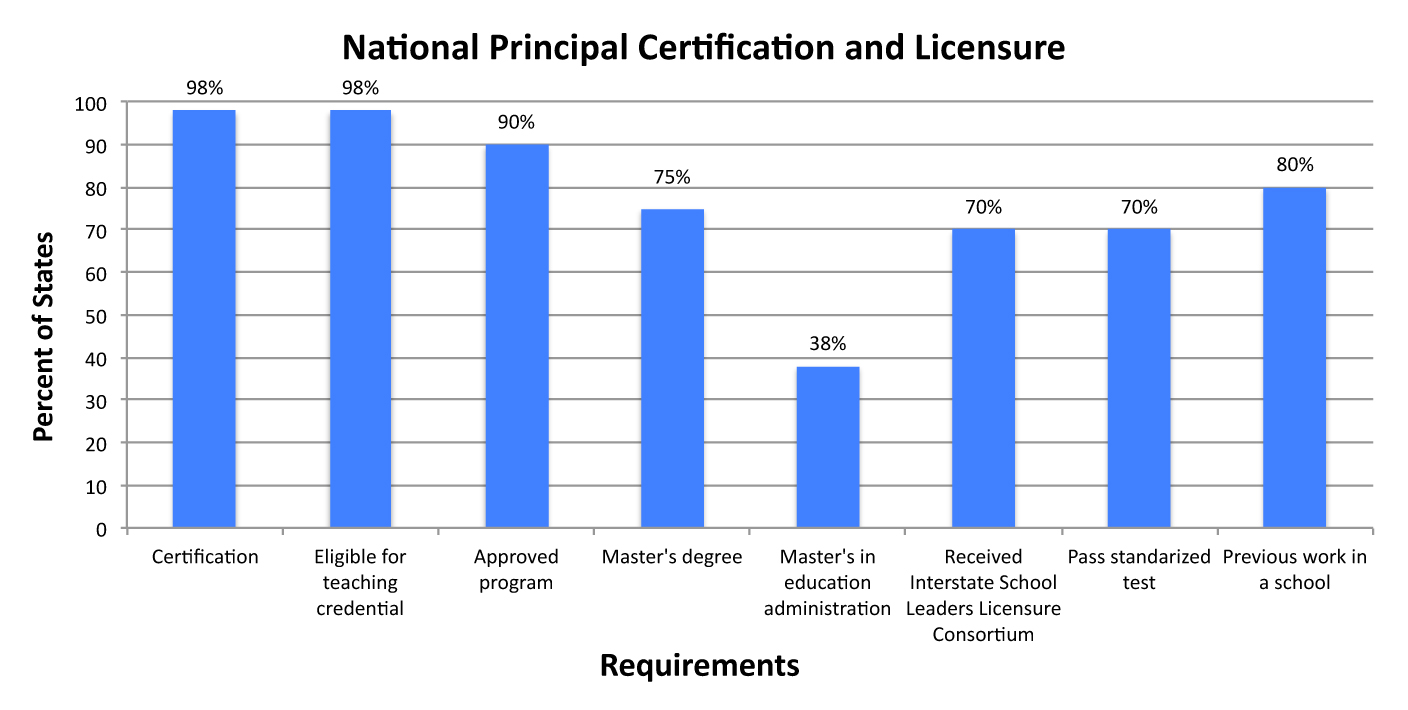

Results: The LeTendre and Roberts (2005) study found the requirements for principal certification and licensure similar across the 50 states. Still, the researchers observed that small differences made reciprocity of certification extremely challenging for principal mobility across state lines.

- All states except Michigan require certification for principals.

- Most states require school principals candidates to

- hold a valid a teaching certificate,

- have experience in a school setting, usually as a teacher,

- hold a master's degree,

- pass a standardized assessment about school leadership,

- participate in a practicum or internship as part of pre-service preparation or during the first years as a principal,

- be recommended by an approved institution of higher education,

- submit college transcripts and pay a fee, and

- submit a criminal background check and/or fingerprints as a condition for certification or employment.

- Most states offer a K–12 certificate that principals must renew by engaging in continuing education courses or professional development activities.

- A large majority of states base their certification requirements on a foundation of explicit leadership standards, with the Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium standards being the most prevalent.

- Few states provide an alternate route for certification.

- Many states have a two-tiered structure that includes an initial certificate with additional requirements for a principal to move to an advanced certificate.

Predictions

The study offered 15 forecasts to guide policy makers. Most of the predictions suggested that significant reform was around the corner, but the authors were clear that changing the system would be daunting. The study saw increasing pressure on principal preparation and certification coming from the federal government, state and local stakeholders, and private foundations and think tanks. It forecast a growing need for qualified principals but expected that efforts to expand the pool of candidates by developing alternative certification routes would produce insufficient numbers of newly qualified leaders. Finally, the study asserted that certification requirements would remain idiosyncratic with little chance of national standards, notwithstanding a prediction that is almost certainly going to hold true: "Good schools will continue to rely on good leaders."

Implications: The need for rigorous principal training and licensure has never been greater (Levine, 2005). The formidable challenges to change include 50 separate state certification processes that must be coordinated. However, the relatively small differences in licensure standards across the country and the almost universal acceptance of the need for reform support the efforts of reformers and the LeTendre and Roberts study's predictions of imminent change. Unfortunately, since the release of the study in 2005, significant reform in attracting and training quality leaders has failed to materialize.

Study Description: The study examined state reports compiled by the National Center for Education Information (NCEI). The researchers also complied data from state officials using telephone and email surveys, and augmented NCEI information by visiting state websites, consulting with state departments of education, and reviewing information contained in the National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification Manual on the Preparation and Certification of Educational Personnel 2004, 9th Edition. In some instances, the researchers needed to review the state statutes on certification of principals.

Citation: Finn, C. E., Jr., & Broad, E. (2003). Better leaders for America's schools: A manifesto. The Broad Foundation and Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Los Angeles, CA: The Broad Foundation. Retrieved December 10, 2014 from http://www.broadeducation.org/asset/1128-betterleadersforamericasschools.pdf.

Herrington, C. D. & Wills, B. K. (2005). Decertifying the principalship: The politics of administrator preparation in Florida. Educational Policy, 19(1), 181-200.

Leithwood, K., Seashore Louis, K., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation.

* LeTendre, B. G., & Roberts, B. (2005). A national view of certification of school principals: Current and future trends. Paper presented at the University Council for Educational Administration, Convention, Nashville, TN. Retrieved October 2011.

Levine, A. (2005). Educating school leaders. Washington, DC: The Education Schools Project. Retrieved December 2014 from http://www.edschools.org/pdf/final313.pdf.

National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification Manual on the Preparation and Certification of Educational Personnel 2004, 9th Edition.

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674. Originally published online September 23, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2011, from http://www.palmbeachschools.org/dre/documents/meta_lead_2008.pdf

• Study from which graphed data were derived.